Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all at Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd for their painstaking work in bringing this book to life. In particular I have to thank Neil himself for taking on this project and smoothing its way to completion. Thanks also to editors Morven Dooner and Sallie Moffat, copy-editor Kate Blackadder, book designer Mark Blackadder, cover designer Robbie Porteous and cartographer Don Williams.

At Dunoon, special thanks to Mairead McGillivray and Sallie Condy at the Community Education Centre for humorous and tolerant assistance when the computer became an even bigger mystery to me than usual.

Also, special thanks to my brother, Ronald, for his endless patience and good humour while assisting with proof-reading, for offering useful opinions and for so kindly keeping me company on field trips around the islands and up and down mountains throughout the west coast of Scotland and for so often gleefully pointing out that what I fondly imagined was a golden eagle in flight above me was, in fact, a crow!

The publisher and I have made every effort to contact all owners of copyright material in this book. Regrettably, in some instances, we were unable to obtain permissions for these, as we could not trace the ownership of the material. In the event that any reader can help NWP in tracing the rightful owners of these sources, they would be extremely grateful if information could be passed directly to them.

I am indebted to the following for permission to reproduce:

Extracts from The Lands of the Lordship, Argyll Reproductions Ltd, Islay:

Extracts from IF Grants Lordship of the Isles, Mercat Press, Edinburgh:

Translation of Bjorn Cripplehands Poem from the Heimskringla, Alfred P Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, Edinburgh University Press, 1989:

Translation of A Bhirlinn Bharrach, Mr Murdo MacLeod, Inverness:

Poetry by Kenneth MacKenzie from The Highland Clearances by John Prebble, published by Martin Secker & Warburg:

Extract from James Hunters Scottish Highlanders, Mainstream Publishing Co Ltd, Edinburgh:

Illustrations from Ian Atkinson, The Viking Ships, Cambridge University Press, 1979 Cambridge University Press:

Illustration by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen The Viking Ship Museum, Denmark:

Photographs University Museum of Cultural Heritage University of Oslo, Norway:

Map from Dr David Caldwell, The National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh:

CHAPTER ONE

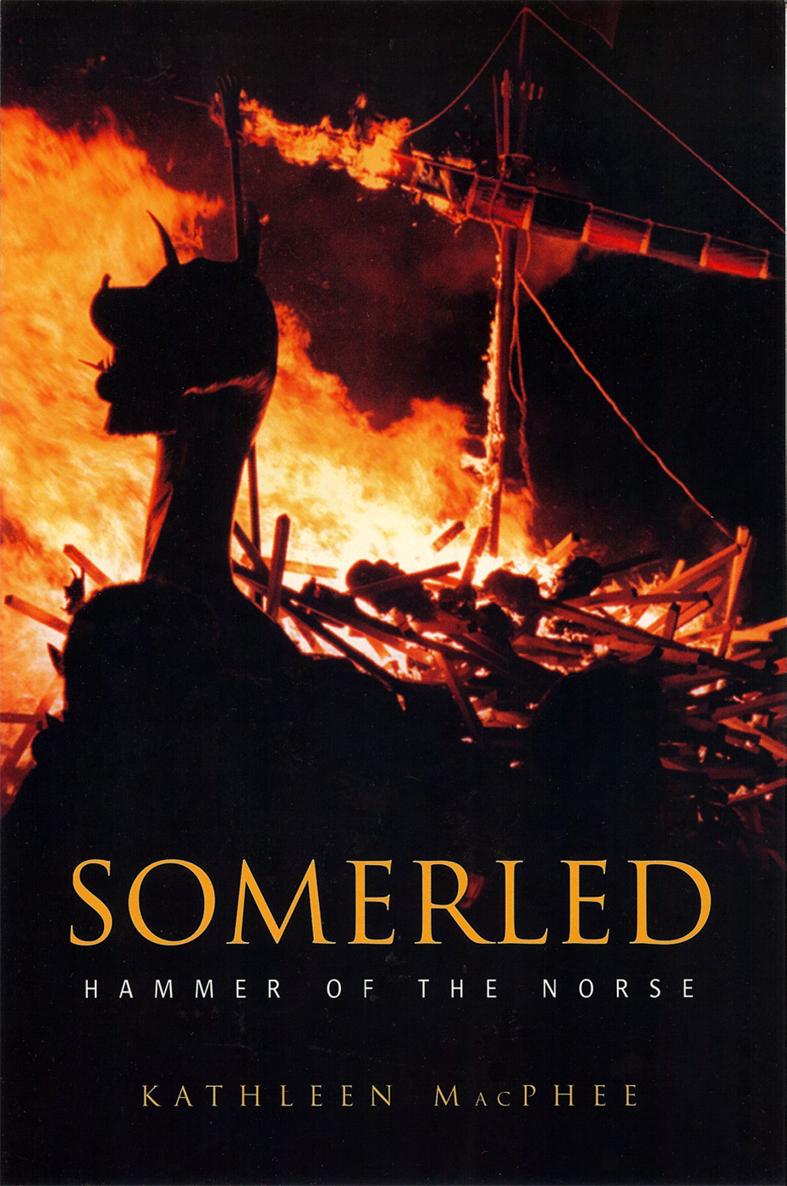

Scotland 1100 AD

From the wrath of the Vikings,

Good Lord, deliver us!

T o the mid-twelfth-century Gaels of the western seaboard of Scotland it must have seemed as if the Good Lord did indeed send someone to deliver them and that person was Somhairle Mr MacGhillebhride, future King of Argyll and Lord of the Isles.

He was the most important leader of Gaelic Scotland after King Kenneth MacAlpin, who brought about the union of the Scots and the Picts in the ninth century, thus beginning the long process leading to the final unification of Scotland as a sovereign nation. But for Somerled, Scotland might have become an extension of Norway, or at least have been controlled by Viking Scandinavians, whether as part of Norway itself, or as an independent Norse country in the west. It was he who brought about the Gaelic revival that eventually crushed the effects of the Norse occupation of the western Highlands and islands.

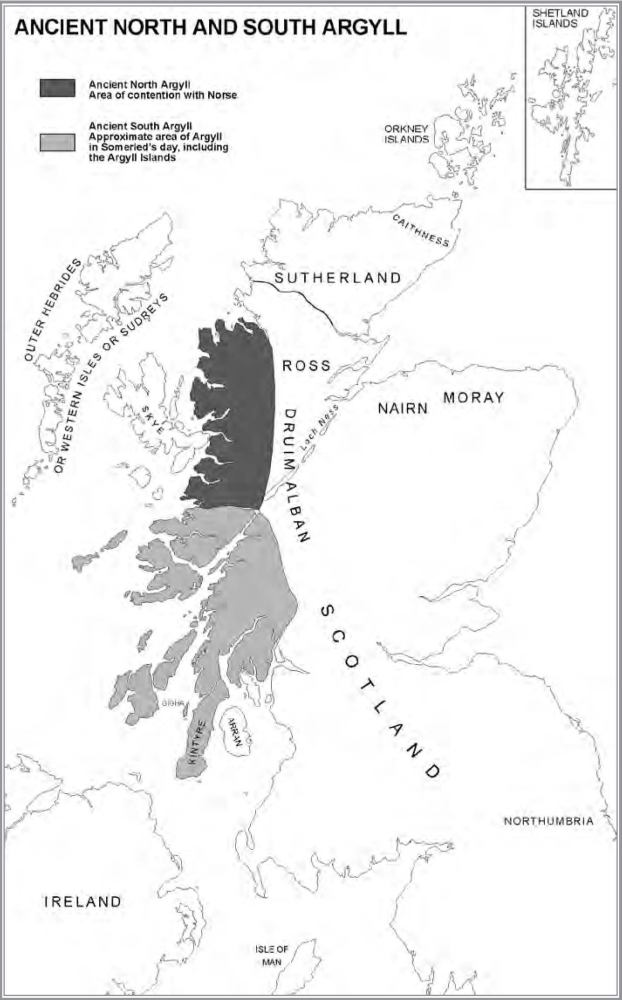

The state of the population of Scotland about the year 1100 was, roughly, as follows: The northern mainland, Caithness and Sutherland, was Norse, under the control of the Norwegian king. The Norse Kingdom of Man and the Isles, subject to the Kings of Norway and the Kings of Scotland, contained a mixed population, now mainly Norse, although originally Celtic, especially in Man itself. The Hebrides contained the native Scoto-Irish Gaels, now threatened with extinction by the intruding Norsemen. Inevitably the two opposing races gradually intermingled, including the nearly submerged Picts and, by Somerleds time a mixed people, the Gall-Gidheil, had evolved. They were looked down upon by the purebred Gaels, who held their bloodlines in the highest regard.

The great Celtic province of Moray was home to a wholly Gaelic population, and comprised the area of the modern counties of Ross, Moray, Nairn and north-east Inverness.

The Scotland of the twelfth century was limited to the area enclosed by the Moray border to the north, the mountains of Druim Alban to the west and Northumbria to the south a constantly moving border as battles raged to and fro.

It was the tension between Celt and Norseman over possession of the western mainland and islands that exploded into open confrontation between the latter and Somerled, the son of a dispossessed Celtic chief of Argyll, and which led to the eventual expulsion of the Norse from the entire country, now known as Scotland, in the fifteenth century.

So who, exactly, were the enemy?

Is acher ingaith innocht: fufuasna fairge findfolt

Ni agor reimm mora minn dondlaechraid lainn na lothlind

(Bitter is the wind tonight: it tosses the seas white hair I do not fear the coursing of a clear sea by the fierce warriors from Norway)

These lines, written by an unknown Irish monk of the ninth century, give an indication of who the aggressors were. The word lothlind is old Gaelic for Lochlann, ie Norway, so there was no doubt in his mind as to where the attackers came from.

The word Dane is sometimes used to refer to Norse attackers, both Danish and Norwegian, in the western seaboard but usually Dane refers to the Dubh-Gall (Black Foreigners or Strangers) coming from Denmark to plunder the east coasts of England. Generally speaking most writers agree that the Viking invaders of the northern mainland of Scotland, especially Caithness and Sutherland, and the Western Isles, were Fionn-Gall (White Foreigners or Strangers) or Norwegians.

A wild and stormy sea was indeed often the only protection the Gaels had against the barbaric cruelty of the Vikings, as the Scottish kings appeared impotent or indifferent regarding the west. Heimskringla, Magnus Barelegs Saga, 1098, describes a meeting between King Magnus of Norway and King Malcolm of Scotland in which the kings made peace between them, to the effect that King Magnus should possess all the islands that lie to the west of Scotland between which and the mainland he could go in a ship with the rudder in place.

Magnus very cunningly sat at the helm of a light ship with its rudder in place, and had it drawn across the isthmus between West Loch Tarbert and East Loch Tarbert, thus claiming possession of the considerable peninsula of Kintyre. In fact, at the time of Magnus expedition Edgar was king of Scotland. Malcolm III had died in 1093. The treaty might have been made with a pretender to the throne. But the intention clearly was that the Norse should stay on the islands and leave the mainland alone, as not only was the king of Scotland too involved with plundering the rich Northumbrian lands to the south, and fending off incursions by challenging Celtic chiefs to the north, but also he obviously considered the west less important and productive than the eastern coasts.