CASS LIBRARY OF AFRICAN STUDIES

AFRICAN PREHISTORY

No. 3

General Editor: Professor BRIAN FAGAN

Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara

M EDIAEVAL R HODESIA

AFRICAN PREHISTORY

No. 1. Gertrude Caton Thompson

The Zimbabwe Culture. Ruins and reactions (1931).

With a new introduction by the author.

Second Edition

No. 2. L. S. B. Leakey

The Stone Age Cultures of Kenya Colony (1931).

With a new introductory note by the author.

New Impression

No. 3. David Randall-Maclver

Mediaeval Rhodesia (1906).

With an introductory note by Brian Fagan.

New Impression

No. 4. James Theodore Bent

The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland: being a record of excavation and exploration in 1891 (1892; 3rd ed. 1895).

New Impression

No. 5. Richard Nicklin Hall

Great Zimbabwe, Mashonaland, Rhodesia: an account of two years examination work in 19024 on behalf of the Government of Rhodesia (1905).

New Impression

No. 6. Edward Humphrey Lane Poole

The Native Tribes of the Eastern Province of Northern Rhodesia. Notes on their migrations and history (2nd ed. 1938).

New Impression

No. 7. Miles Crawford Burkitt

South Africas Past in Stone and Paint (1928). With a new preface by the author.

New Impression

No. 8. Astley John Hilary Goodwin and Glarence Van Riet Lowe

The Stone Age Cultures of South Africa (1929).

New Impression

No. 9. Louis Pringuey

The Stone Ages of South Africa as represented in the collection of the South African Museum (1911).

New Impression

No. 10. Anthony John Arkell

Shaheinab. An account of the excavation of a Neolithic occupation site carried out for the Sudan Antiquities Service in 194950 (1953).

New Impression

FRONTISPIECE

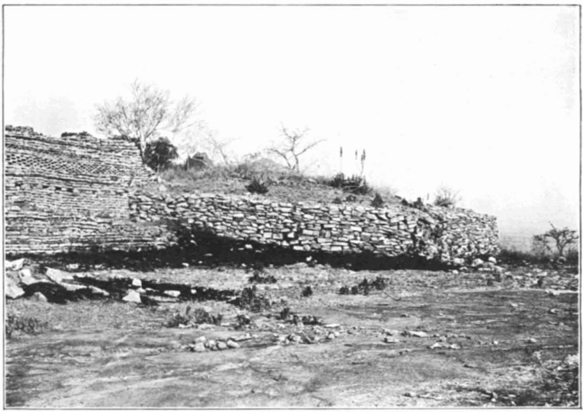

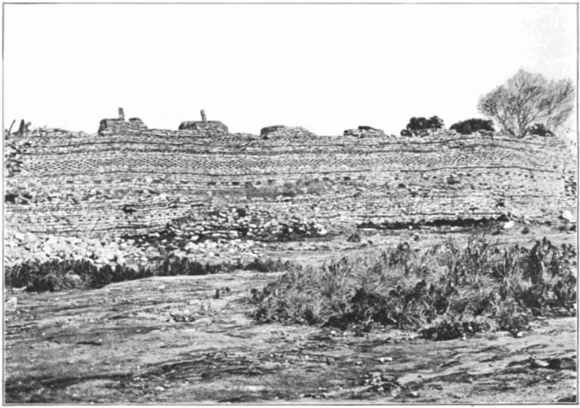

(a) NANATALI, FRONT. See pages 51-55.

(b) NANATALI, FRONT. See pages 51-55.

M EDIAEVAL R HODESIA

by

David Randall-MacIver

With a new introductory note by

Professor Brian Fagan

Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara

This impression first published by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

This edition published by Routledge - 2012

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Introductory note Copyright 1971 Brian Fagan

All rights reserved

| First edition | 1906 |

| New impression with a new introductory note | 1971 |

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

ISBN: 978-0-714-61885-2 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-136-25765-0 (ebk)

To

Sir Lewis Michell

Whose Interest in Archology

Originated the Researches Therein Described

This Volume is Dedicated

Introductory Note

The monograph which is reprinted here was an important landmark in the investigation of the Zimbabwe Ruins. In the early years of this century, it was the custom of the British Association for the Advancement of Science to hold regular meetings in various countries of the British Empire, in order to encourage sdentific research in other parts of the world. The Association planned a meeting in South Africa in 1905 and commissioned a young archaeologist from England, Dr. David Randall-Maclver, to carry out excavations at Zimbabwe and to report on the significance of this remarkable monument.

Randall-Maclver was the first professional archaeologist to examine the Ruins and was well qualified to do so. Although he had no African experience he was trained by the eminent Egyptologist, Sir Flinders Petrie, a pioneer in sequence dating and typographical analysis. Maclvers methods were vastly different from those of Bent and Hall and others who had preceeded him. He investigated other ruins as well as Zimbabwe, and took careful note of the minor domestic finds made in his trenches, in contrast to earlier investigators who tend to concentrate on more flamboyant artifacts and exotic objects. He made comparisons between the pottery of Zimbabwe and that of the people living in the area in 1905. His careful use of African artifacts and of comparisons with modem material culture, led him to believe that the people who inhabited Zimbabwe were related to the inhabitants of the area in the early 20th century. As Summers points out, his approach was in direct contrast to that of his antiquarian predecessors for he used ail the objects found at the site as evidence, and not just a selected few. He had no preconceived ideas, and used new methods of dating to establish a relative chronology of the various periods of occupation of the Rhodesian ruins, by careful study of the imported porcelain and china found at Zimbabwe. British Museum experts were able to assign the imported vessel to the 13th century A.D. and later.

In contrast to Hall, Maclver firmly stated that Zimbabwe was of African origin and inspiration and belonged to the Mediaeval period, the date being established by foreign imports the ge of which could be established with some exactitude. The publication of Mediaeval Rhodesia caused a furious academic controversy, led by Richard Hall, who until that time had been regarded as the world authority on Rhodesia in general and on Zimbabwe in particular. Those who assigned a high antiquity to Zimbabwe were bitterly angry. The echoes of this controversy still linger on, but the basic reliability of Randall-Maclvers work was recognized by many serious scientists of the time. His results were broadly confirmed in 1929, when Gertrude Caton Thompson carried out further work at Zimbabwe, again under the auspices of the British Association. But Maclvers early work set the stage for the recognition of Zimbabwe as one of the greatest achievements of prehistoric Africa.

The reader is referred to Roger Summers Zimbabwe: A Rhodesian Mystery (Johannesburg, 1963) for further information.

University of California

1970

Brian Fagan

Preface

THE investigations which are described in this volume were undertaken during the spring and summer of 1905 at the invitation and with the support of the British Association and the Rhodes Trustees. Though the problems of the origin and date of the ruins in Rhodesia had been before the public for a whole generation, from the time, in fact, that Mauch rediscovered Zimbabwe, yet remarkably little progress had been made towards their solution. In part this was due to the difficulty of exploring a country that has only recently been opened up, in part to the concentration of attention upon one single group out of ail the numerous ruins which were available for study, and in part to the want of system with which any excavations had been conducted.

The British Association, when arranging to visit South Africa in 1905, resolved to make an effort to end this uncertainty, and asked me to precede the visitors by some months in order to explore and to prepare a special report upon the subject of the ruins. I reached Southern Rhodesia early in April and continued at work till the middle of September. Owing to the great improvements effected in the means of communication and to the exceptional facilities accorded me, I was enabled to conduct researches over a great extent of country, and to obtain observations which have led to unexpectedly definite conclusions.