This edition is published by Muriwai Books www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books muriwaibooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1927 under the same title.

Muriwai Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

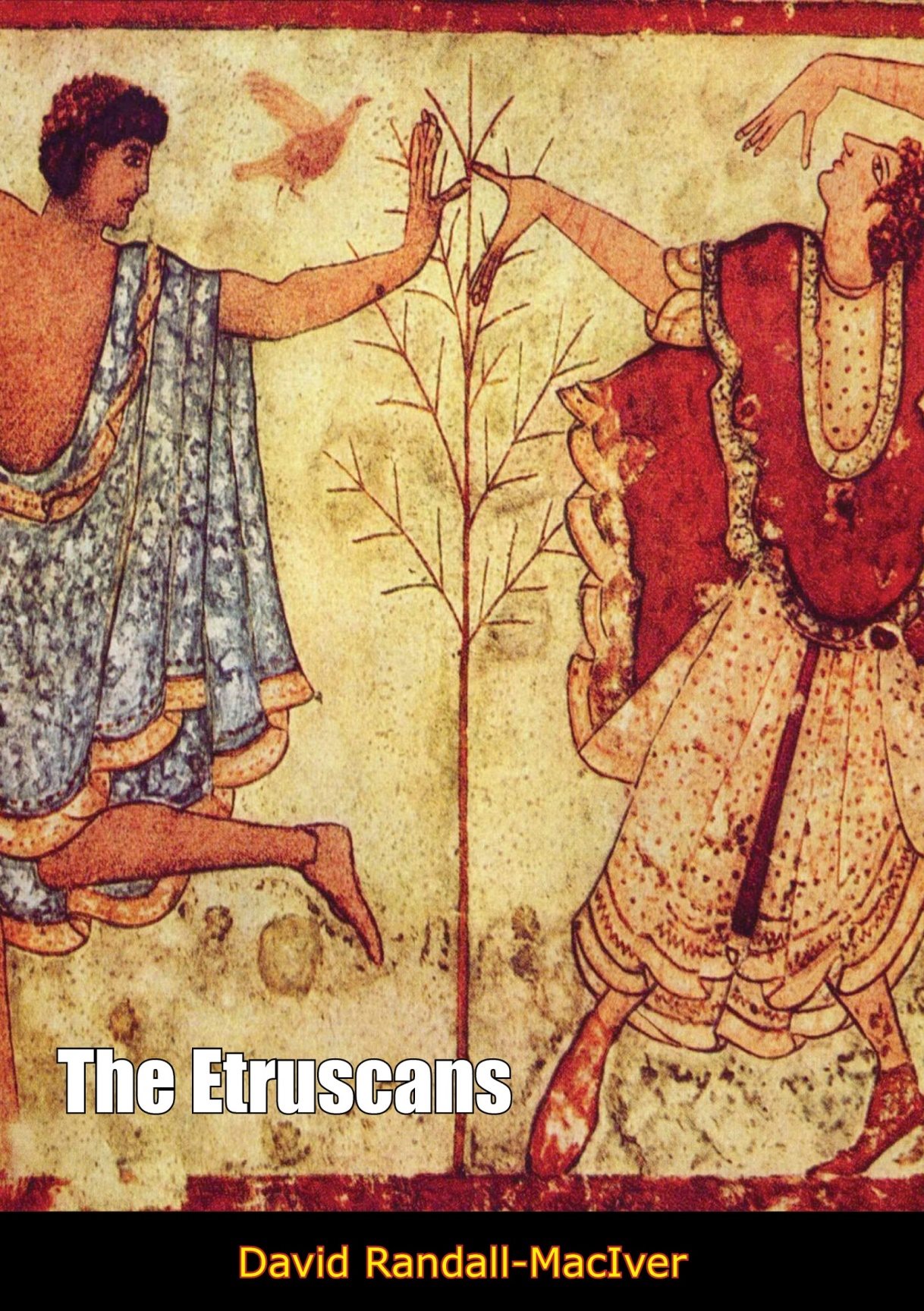

THE ETRUSCANS

BY

DAVID RANDALL-MACIVER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The Apollo of Veii. Photograph, Alinari Frontispiece

1. Scenes of daily life. From an engraved situla . Photograph, Proni

2. Engraved silver bowls from Caere and Praeneste

3. A noble and his wife. Sarcophagus from Caere. Photograph, Alinari

4. Gold and silver from a tomb at Caere.

5. Gold work from a tomb at Caere.

6. Frescoes in the Tomb of the Leopards at Corneto. From Montelius, Civ. Prim, en Italie

7. External view of the Great Tumuli at Caere. Photograph, Alinari .

8. Interior of the Tomb of the Stuccoes at Caere. Photograph, Alinari

9. Cauldrons of hammered bronze from Vetulonia. After Not. Scavi , 1913

10. Contents of a circle tomb at Vetulonia

11. Fibulae of gold from tombs at Vetulonia.

12. Gold fibulae and bracelets from Vetulonia

13. The bronze Chimaera from Arezzo. Photograph, Alinari . To face

14. The Orator. A bronze statue from Lake Trasimene. Photograph, Alinari

Three versions of the earliest Etruscan alphabet.

Map showing principal Etruscan sites

CHAPTER 1

Ruskins opinion; Why the Etruscans are interesting; Continuity of life and character in Tuscany; Extent of Etruscan domination; Untrustworthiness of literary evidence; Origin according to Herodotus; Untenable theories of other writers as to origin; The Etruscans were immigrants from Asia Minor; Date and manner of their arrival; Derivation of the name; Possible connexion with Tursha.

THERE are few people to whom it would be quite a natural thing to go on the first day after their arrival in Florence to the Museo Archeologico. It seems to have so little to do with all the varied interests and enthusiasms which have brought them to Italy. They have come here to live again in the glorious days of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, to see the works of Giotto and Donatello and Michelangelo, to wander and dream in the streets where Dante trod. Very early in his pilgrimage, therefore, the ardent lover of art will no doubt wend his way to the cloisters of Santa Maria Novella and open the well-known pages of his Mornings in Florence . But there, perhaps, some passages in that classic homily will strike him with sudden force. He may be surprised to realize that Ruskin lays great stress on the Etruscan origin and descent of the great Florentine painters: Central stood Etruscan Florence...Child of her peace and exponent of her passion, her Cimabue... Or again: Cimabue, Etruscan-born gave...eager action to holy contemplation.

This may lead to reflection. Our pioneer teacher in Italian art is declaring that the Etruscans are not a mere phantom of the past, is stating that they have played an important part in the formation of the Italy that we love. It must be worthwhile, then, to know more about them. Ancient history is baffling and contradictory, but out of all the myths and legends and poetic distortions certain facts stand out clearly. It is plain, for instance, that the Etruscans were once the most important people in all Italy, and that they did more than any others to mould its civilization. The Romans themselves owed much of their religion and much of their political, social, and military organization to the Etruscans. Moreover, when they conquered Central and Northern Italy the Romans found it permeated all through with a very advanced civilization, which they themselves could never have produced, though they were fortunate enough to inherit itand this civilization was the work of the Etruscans.

Ruskin, with the insight of a great critic, has divined rightly when he suggests that to appreciate the work of a fourteenth-century painter in Tuscany we must study his history and origins, the soil and the race from which he springs. More than two thousand years of continuous development had gone to the making of Giotto and his school. They did not spring fully armed from the head of any Byzantine; many centuries of thought and observation and study had unconsciously prepared their birth. So it was also with their mightier successors; not only Dante but even Michelangelo owes the possibility of his existence to an Etruscan ancestry, spiritual as well as physical. It was by no mere accident that Niccol Pisano, the earliest of the great sculptors, found his first models in the old sarcophagi of the Campo Santo at Pisa. He was really discovering his own parentage and returning to the natural inspiration of his race. Often we may think that the earliest work of the Pisani and the drawings of Giottos pupils repeat mannerisms peculiar to Etruscan sculpture and painting, but, if so, these are only the superficial expression of a spiritual identity which goes far deeper. The temperament and outlook of any Tuscan artist in the Middle Ages or the Renaissance are directly inherited from a long line of ancestors, whose works are to be seen in such places as the Museo Archeologico. It is, therefore, no dry or dusty study into which I would lure the reader; on the contrary it is a subject which lies at the core of everything which interests him as well as me, in the city of Florence and the work of her greatest men.

The continuity of life and customs in Tuscany is very remarkable, and very important to understand. All the changes and chances of history have left this heart of Central Italy essentially the same that it has been for about three thousand years. Never swamped by any foreign invasion the race has remained unchanged. Just as you may recognize today in the streets of Florence the living replicas of men and women painted by Ghirlandajo, so you must realize that pictures of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are made by the lineal descendants of those who frescoed the walls of their rock-tombs in Etruria centuries before the birth of Christ.

Even in externals there are many obvious survivals. The loggia of a modern Tuscan house finds its precise equivalent in models carved in stone about 400 B.C. Work in the fields and vineyards is little different from what it was when the Etruscans planted the olives and introduced the vine. The stornelli , those improvised epigrams which the labourers fling at one another or at the bystander as they till the soil, are only modern equivalents of the Fescennine verses mentioned by Horace. Even in the folklore and superstitions of the countryside there may linger faint reminiscences of deities dethroned; the red-capped goblin of the peasant is perhaps an Etruscan god. Sometimes I even think that the rough aspirations of the lingua toscana , which are like the burr of our own north-countrymen compared to the softer accents of other provinces, may be inherited from the pre-Italian language with its notoriously harsh consonants.

Next page