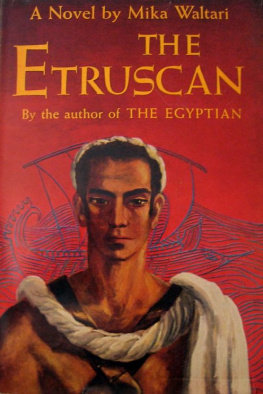

Some of the most powerful human images and symbols are those related to male and female, sex and marriage, and the nursing mother. It is in just these areas that Etruscan life and ideals differed most radically from those of the Greeks and Romans.

In contrast to the sources available for the history and habits of Greece and Rome, whose rich tradition of historical and literary texts can tell us what these classical people said and thought about the subjects of gender, families, women and children, the evidence available for Etruscan customs is archaeological and visual. Unfortunately, no literary texts by the Etruscans have come down to us no epic, drama or lyric poetry. We only have half a dozen religious inscriptions dedications, contracts, liturgies, religious calendars and some 9,000 very brief epitaphs (see This chapter will focus on what we know of the situation of women and children in the world of the Etruscans and how it differs from the reality and the ideals of the classical Greek world with which we are so much more familiar.

Their art and material culture illustrate Etruscan customs, beliefs and ideals, but these must be translated just as Greek and Latin texts must be translated in order for us to properly understand them. Just as the Etruscans used the Greek alphabet to write in their peculiar language, Etruscan artists and craftsmen used the vocabulary of Classical Greek art to express their particular rituals, customs and beliefs, and to represent the world around them a world in which the status of women was very different from other classical societies.

Etruscan Women

There is not much about the Etruscans in Greek and Latin literature. The longest single literary passage, however, an account by the fourth-century historian Theopompus, quoted in Athenaeus later scandal-mongering compilation, Deipnosophistae, Sophists at Dinner, deals with Etruscan sexual customs, and emphasizes the role of women in Etruscan social life. The Greek author has much to say about the shocking behavior of the Etruscans. They share women in common and display a total lack of shame or modesty, showing themselves naked and speaking openly about sexual intercourse. Etruscan women are beautiful, powerful and promiscuous, mingle freely with men, recline with them on the same couch, and even offer toasts at the banquets and drinking parties that were for the Greeks traditionally all-male events. These banquets, because of their sexual license and lack of restraint, were orgies rather than normal social occasions. Here is the passage:

Among the Etruscans, who were extraordinarily pleasure-loving, Timaeus says that the slave girls wait on the men naked. Theopompus, in the forty-third book of his Histories, also says that it is normal for the Etruscans to share their women in common. These women take great care of their bodies and exercise bare, exposing their bodies even before men, and among themselves: for it is not shameful for them to appear almost naked. He also says they dine not with their husbands, but with any man who happens to be present; and they toast anyone they want to.

And the Etruscans raise all the children that are born, not knowing who the father is of each one.

It is no shame for the Etruscans to be seen having sexual experiencesfor this too is normal: it is the local custom there. And so far are they from considering it shameful that they even say, when the master of the house is making love, and someone asks for him, that he is involved in such and such, shamelessly calling out the thing by name. When they come together in parties with their relations, this is what they do: first, when they stop drinking and are ready to go to bed, the servants bring in to them with the lights left on! either hetairai, party girls, or very beautiful boys, or even their wives.

When they have enjoyed these, they then bring in young boys in bloom, who in turn consort with themselves. And they make love sometimes within sight of each other, but mostly with screens set up around the beds; these screens are made of woven reeds, and they throw blankets over them. And indeed they like to keep company with women: but they enjoy the company of boys and young men even more.

And their own appearance is also very good-looking, because they live luxuriously and smooth their bodies; for all the barbarians in the West shave their bodies smooth They have many barber shops.

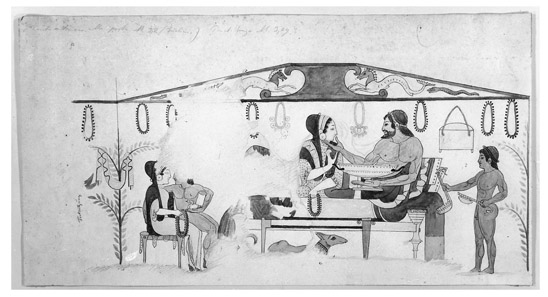

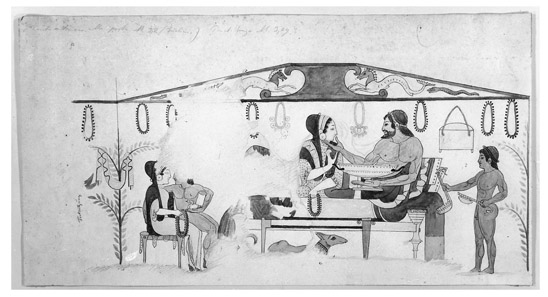

Athenaeus also quotes the remark of Aristotle, that Etruscans eat with their wives, reclining at table with them under the same blanket, and that Etruscan slaves are very beautiful and dress better than is the custom of slaves.

There are all the standard charges and clichs of Greek truphe or Roman luxuria the love of ease and pleasure of an exotic people, the lust and luxury characteristic of the barbarian way of life, the fancy barbers and emphasis on physical beauty, the promiscuity, the wild parties and lack of modesty Etruscans allegedly are not even ashamed to have intercourse with the lights on.

Yet a comparison of this description with the picture derived from archaeological discoveries and Etruscan art allows us to distinguish some of the reality behind the scandal-mongering gossip. Sixth-century BC archaic tomb paintings of Tarquinia illustrate the ideals, realities and conspicuous consumption of aristocratic ceremonies, and the life of the members of the noble families who set up these tombs as monuments to their wealth and prestige. The banquet scenes painted on their walls offer striking parallels to those

There is more that can be said about two specific passages. The authors remarks on the great care the women take of their bodies, and their custom of exercising naked, exposing their bodies even before men, and among themselves, for it is not shameful for them to appear almost naked, may refer to Sparta, where the women exercised like the men, and thus joined them in an exclusively male context. To an Athenian, the custom appeared strange and even perverse. Plato advocated adopting it but only in theory.

The statement that women can raise any children they have, on the other hand, may well be based on a real difference between Greek and Etruscan attitudes to the exposure of children at birth. Jews and Egyptians were said to rear every child that was born to them. The Germans did not limit the number of children, and considered it shameful to expose them to die. Etruscan wealth and resources would also have allowed them to indulge a love of children and avoid resorting to exposure of newborn babies, as was the custom for ancient Greeks during most of their history.

The passage might also refer to the legal situation of Etruscan women, who could perhaps bring up their own children no matter what the status of the father, a situation Greek laws did not permit. In Greece and Rome, the father decided whether a child should be brought up or exposed. An Etruscan upper class woman, in contrast, could pass on her status, and perhaps her property, to her children.

Tomb of the Painted Vases, Tarquinia, rear wall. Married couple attending a banquet reclining on the same couch. To the right, a naked cupbearer, on the left, seated, their children. C. 500 BC . ( MonInst 186973, pl. 13).

The Etruscan Aristocracy

The basic element of society in classical Greece was the male citizen and soldier. In Rome it was the pater familias. In Etruscan society, which retained its aristocratic nature throughout its history, it was the married couple that represented one generation in the continuous chain of generations of a great family in which the wifes noble birth was as important as that of the husband. This Etruscan aristocracy arose at a certain point in the history of the cities between the Arno and the Tiber, when it marked the juncture between prehistory and history. Archaeology can trace its development from the necropoleis, the cities of the dead, whose rich graves provided these great families with an opportunity to exhibit their wealth, connections and prestige.