Third Edition

David Sansone

This third edition first published 2017

2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd (1e, 2004), John Wiley & Sons Ltd (2e, 2009)

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of David Sansone to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for.

9781119098157 [paperback]

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Konstantinos Kontos / Photostock

FOREWORD LOOKING BACKWARD

In his last public speech in Mississippi City, March 1888, Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States of America, proclaimed, The past is dead, very much hoping that what he was saying might turn out to be true. Another Southerner, the novelist William Faulkner, issued a stern corrective when, in his Requiem for a Nun (1951), he put into the mouth of a citizen of the fictional city of Jefferson, Mississippi, the following: The past is never dead. Its not even past. The past, it seems, will always be with us, whether we like it or not. But it will not always be the same past. Rather, the past is in a constant process of change, as the ever-changing present increasingly imposes itself on the past. It is, perhaps, difficult to accept the notion that, for example, the civilization of the ancient Greeks, a civilization that no longer exists, is now in the process of change. We are, however, quite prepared to admit that ancient Greek civilization, while it was in existence, was constantly changing, since change is an invariable feature of living civilizations. One of the important ways civilizations, including our own, change is by constantly modifying the perception of the shared past that serves as each civilizations foundation. As we will see, ancient Greek civilization was involved in a constant process of reinventing itself, by adapting its own past in the light of its own ever-changing present. We, too, have been reinventing ancient Greek civilization in a similar fashion. This process of reinventing ancient Greek civilization has been going on for quite some time. Indeed, there is a venerable tradition of doing so, a tradition that stretches from the time of the ancient Greeks themselves until this morning.

Reinventing Ancient Greek Civilization

Let us begin at a point within that tradition, somewhat closer to this morning than to the time of the ancient Greeks, so that we may have a better idea of what the nature of that tradition is. Lucas Cranach the Elder, who lived in sixteenth-century Germany, was court painter to Friedrich the Wise, Elector of Saxony, and friend of Martin Luther. Among Cranachs works, which include paintings of biblical subjects and austere portraits of princes and Protestant reformers, are representations of stories from Greek myth, among them a Judgment of Paris now in New Yorks Metropolitan Museum of Art (). In short, despite the fact that Cranachs painting purports to provide a pictorial representation of ancient Greek myth, the terms in which the myth is portrayed are recognizably those of sixteenth-century Germany.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (14721553), The Judgment of Paris, oil on wood; 102 71 cm, ca. 1528.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1928. www.metmuseum.org (accessed March 29, 2016).

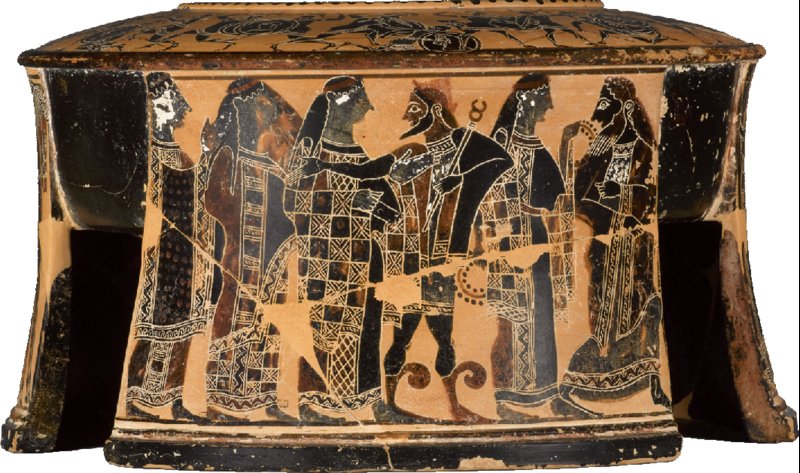

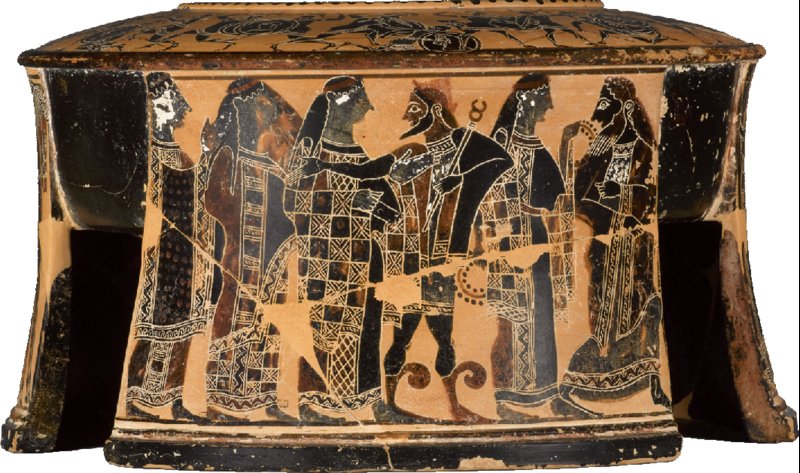

Attic black-figure tripod-jar showing Hermes (center) leading Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite to Paris (right) for judgment; height 14 cm, ca. 570 BC. Paris, Muse du Louvre, CA 616 C.

Source: Photo RMN-Grand Palais (Muse du Louvre) / Stphane Marchalle.

It is easy enough to spot the inauthentic elements in Cranachs Judgment of Paris (or in some more recent depictions of ancient Greece, such as the films Hercules or 300: Rise of an Empire). It is much more difficult to say what is genuine. But what do we mean, in this context, by genuine or authentic? The story of the judgment of Paris is just that: a story. It is concerned with gods and goddesses who never existed (although they were, of course, thought to exist) and with human beings who may or may not have existed and who may or may not have done what the story represents them as having done. Still, stories can tell us a great deal about the people among whom the stories circulate. Surely there is an authentic (or at least a more authentic) version of the story of the judgment of Paris which, if we can reconstruct it, will help us recover something of ancient Greek civilization? In any case, the ancient Greeks have a history. Can we not discover at least some facts about the ancient Greeks, or at least about some of the ancient Greeks?

As we will see, the English word history and the English word story have the same origin. They both derive from the Greek word historia, which was used by the Greeks of the fifth and fourth centuries BC to mean investigations or the account derived from ones investigations. (The ancient Greek word for story, by the way, is

Next page