To my parents,

John and Edith,

who taught me the transformative power of books.

You are loved.

You are missed.

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright John B. Kachuba 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789140798

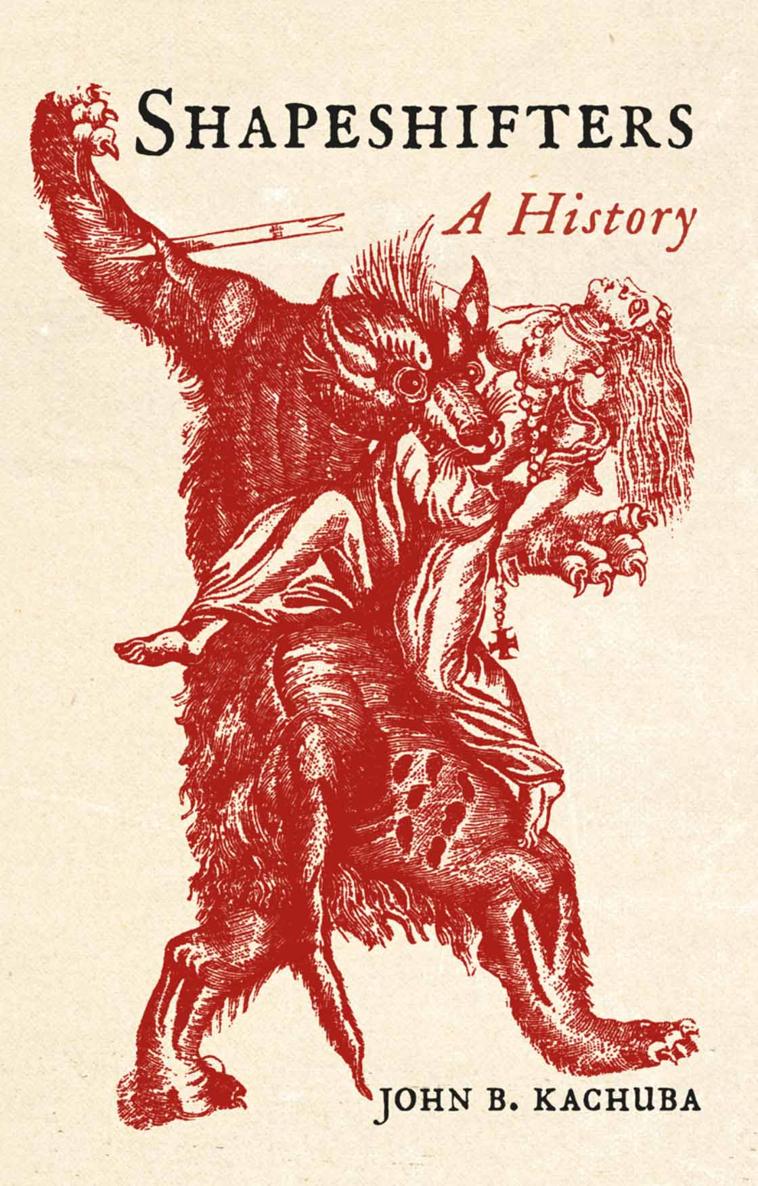

Introduction

Entering the World

of the Shapeshifter

A s night falls, a desperate figure cowers in the forest, terrified and yet excited as he ponders what is about to unfold. The Moon rises full and round over the forest, and he is caught in its ghostly luminescence.

That is when the change happens.

Painfully, his bones stretch and grind as they shift into new positions. On all fours, his clothes shred, and his new, sleek, muscular body emerges. He watches in amazement as the nails on his hands and feet elongate into razor-sharp claws. Thick fur sprouts from his new paws. His face, his entire body are now covered in fur. Casting his large yellow eyes up to the Moon, saliva dripping from fanged teeth, he throws back his head and howls, a long, pitiful cry echoing through the forest.

The werewolf is born.

The werewolf, a person who transforms into a wolf at each full moon, is an example of a shapeshifter, a person who can change from a human form to that of an animal, either through his own agency or that of an outside source. Another shapeshifter stereotype is the vampire changing into a bat think Count Dracula of the silver screen.

Shapeshifters are not new. Since ancient times, people from cultures all around the world have speculated on the possibilities of human beings transforming themselves into animals, or mythological creatures, and then returning to their human natures. Prehistoric cave drawings discovered in Arige, France, depict creatures that are half-animal and half-human, evidence of an ancient belief in shapeshifters. Primitive man knew that his life and the lives of the animals in his environment were inextricably bound together. He could hunt these animals for food, but they could just as easily hunt him for the same reason, especially when his animal adversaries often held the advantages of cunning, speed and strength.

But what if he could meet the animals on their own terms? What if he could develop the cunning of a fox, the speed of a cheetah or the strength of a lion? Surely, then, he would stand a much better chance of being the eater, rather than the eaten. It is entirely possible that this ancient yearning of man to become animal, at least temporarily, gave rise to the belief in shapeshifters.

In Native American and other indigenous cultures, it is common for hunters to don ritual costumes that mimic the appearance of certain animals, especially those animals hunted for sustenance, and to imitate their movements in dance rituals. But these dances are not simple mimicry; rather, the dancers believe they take on the animals spirit, that in fact they become the animal and, by doing so, gain inside information relative to the animals location and migration, thereby ensuring a successful hunt. The Plains Indians even went so far as to wear the horns and shaggy hides of bison to get close enough to the herd to make a kill. The manoeuvre was camouflage, but could there have been more meaning attached to wearing the disguise? Did the hunter become another bison?

In the late 1990s, the anthropologist Rane Willerslev spent a year living in a Yukaghir community in northeastern Siberia. Studying the relationship of Yukaghir hunters to the animals they hunted, he wrote from first-hand experience of how the hunters think humans and animals can turn into each other by temporarily taking on one anothers bodies. The hunters would dress in elk hides, walk like elk, take on the elks consciousness, literally thinking, or so the Yukaghir believe, like an elk, to be accepted as an elk by the herd, thereby allowing them access for the kill. But there is a danger to this practice: the Yukaghir believe that an actual transformation could occur, making a hunter lose sight of his human nature, his human soul. As Willerslev puts it, a hunter might lose his original species identity and undergo an invisible metamorphosis.

The Yukaghirs tell of a deer hunter who wandered in the wilderness for hours, unsuccessful in the hunt. He came upon an unfamiliar camp where women fed him lichen, as if he were a deer. He began forgetting things but recalled his wifes name, and it was that recollection that snapped him back to his human nature.

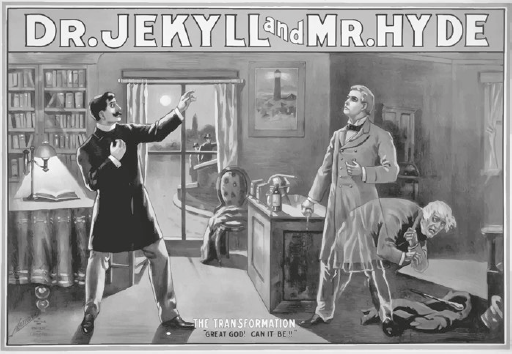

There is something primal about shapeshifters, something that goes beyond simply wishing for the strength and cunning of animal prey. Humans are, of course, animals themselves but animals with a highly developed sense of morality and social mores that are set in place for the good order of the society. We react with indignation and anger when the rules we have set in place are violated by criminals, whether the violations be the petty theft of cigarettes from the corner store, or the wholesale slaughter of entire populations for racial, ethnic or religious reasons. We react that way because we know that we have a primal animal nature within us that must be controlled. But there is also the temptation to throw off the rules that keep our unsavoury behaviours in check and to embrace our animal natures, free of conscience, free of morality. Robert Louis Stevenson illustrated the struggle to keep that animal nature subdued in his memorable The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, in which Dr Jekyll develops a potion that transforms him into the sociopathic Mr Hyde and allows him to indulge his urges in a variety of vices, including murder. But poor Dr Jekyll is unable to control his metamorphosis into Mr Hyde, who becomes more and more dominant, and, in desperation, Jekyll kills himself.

Seen in this light, shapeshifting is a way of shaking off the constraints of society and the bonds of morality, granting licence for one to experience the wild, unfettered life of an animal. Stories abound from antiquity of people transforming into animals for exactly those reasons. Consider Zeus, who in ancient Greek mythology was known as the king, or father, of the gods, the latter a more fitting appellation since he sired many of the gods and goddesses of the Greek pantheon. As lascivious as Zeus may have been, he often needed help to seduce or rape the women and men with whom he had sex. Disguising his divinity through shapeshifting worked wonders for him; among his many shapeshifting conquests, he seduced Europa in the form of a white bull; his sister Hera in the guise of a cuckoo-bird; Leda as a swan; Danae in the form of a golden shower; Antiope in the guise of a satyr; Eurymedusa in the form of an ant; Kallisto in the disguise of the maiden Artemis; and Alkmene, to whom Zeus appeared in the form of her own husband. Another notable example of this form of shapeshifting trickery is found in Sir Thomas Malorys fifteenth-century