Table of Contents

The four Classes of animals which have been considered in the preceding volumes of this series we have seen to have one character in common; viz. the possession of a bony framework within the body, of which a jointed spine is the most essential element. This character, which unites those four Classes into one great group, and gives to that group the name Vertebrata , by which it is distinguished among naturalists, we have seen, however, by slow degrees, deteriorated, if I may use such an expression, from bone to cartilage, and gradually diminished in its development, until, in the lowest of the Fishes, it can scarcely be recognised at all.

I come now to treat of animals in which the bony skeleton no longer exists. The conditions of their existence do not require such a scaffolding on which to build the constituent muscles: many are habitually immersed in water, a fluid the density of which supports their soft bodies; their motions generally lack the precision, energy and variety of those which belong to Vertebrate animals; and where this is not the case, as in the Articulate Classes, the skeleton which affords attachment to the muscles, is not internal, but invests the body, while its substance differs essentially from bone in its chemical composition and its structure.

An immense assemblage of living creatures are included in this category; creatures differing widely from each other in the most important characteristics, so that they cannot be grouped together. The term Invertebrata , by which they are sometimes designated, indicates indeed only a negative character, and we shall be greatly mistaken if we suppose (misled by such a term) that the animals which have a skeleton, and those which are destitute of one, constitute two primary divisions of living beings, of equal or co-ordinate importance.

Several divisions of Invertebrate animals do, in fact, exist, each one of which is equal in rank to the Vertebrata . One of these will form the subject of the present volume, commonly known by the name of Mollusca ; a term invented by the illustrious Cuvier , from the word mollis (soft), and evidently suggested by the softness of their boneless bodies. The appellation can scarcely be considered happy, for the character so indicated is very trivial, and is shared by other animals of totally different structure:objectionable, however, as it is, it has been generally adopted, and I shall not hesitate to make use of it.

As the great Vertebrate Division includes the four distinct Classes of Beasts, Birds, Reptiles and Fishes, so does the great Division of Mollusca contain six Classes, distinguished by characters which I shall presently enumerate. I must, however ever, first indicate those which they possess in common, and by which they are naturally grouped together.

The nervous system demands our first attention. Instead of a great mass of nervous substance accumulated in one place, and a lengthened spinal cord proceeding from it, giving out threads to all parts of the body, as in the Vertebrata , we find the nervous centres numerous, unsymmetrical and disposed in various parts of the system, no one having so decided a predominance over the others in bulk, as to merit the appellation of a brain. There is, however, one mass larger than the rest, which is always placed either above the gullet (sophagus), or encircling it, in the form of a thickened ring; and from this the nerves that supply the organs of sense invariably originate. This mass, or ganglion, must undoubtedly be regarded as the representative of the brain; for in the most highly organized animals of the Division, the Squids and Cuttles (), this encirling mass is enclosed and defended by a case of cartilage, the lingering rudiment of a bony skull.

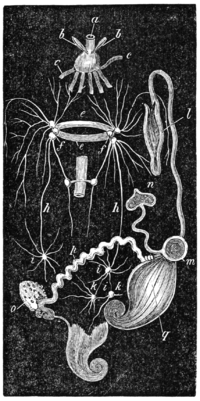

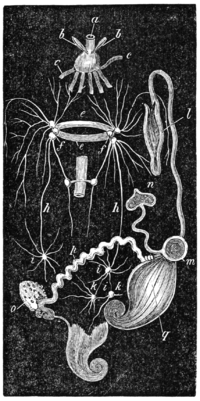

The accompanying engraving, which is copied from Professor Grant 's "Outlines of Comparative Anatomy," will give the reader an idea of the system of nerves and ganglia, with some of the other organs, as they appear in Bulla lignaria , a large and handsome shelled Mollusk found on the British coasts.

In the above figure the chief ganglion forms a ring, (marked

ee,); anterior to this there is a small ganglion, not seen, because situated below the bulb of the gullet (

a), just before the insertions of its diverging muscular bands (

c), and behind the salivary glands (

b). The brain-ring (

e) has on each side a large three-lobed ganglion (

f), whence numerous nerves pass to the surrounding parts, and two long branches (

h) extend backwards along the sides of the abdomen, to two ganglia (

i,

i), placed above the muscular foot.

NERVES OF BULLA Behind these are two sympathetic ganglia, (

k,

k), which send threads to the digestive system, the ovary (

o), the oviduct (

p), the uterine sac (

q) , the vulva (

m), and the urinary organs (

n). This may be considered as a fair average sample of the nervous system in the Mollusca , being selected from a Class presenting neither the highest, nor the lowest forms of organization.

The nervous centres are, for the most part, grouped without regard to symmetry, those of one side not corresponding to those of the other; and this irregularity is characteristic of the whole Division, not only in the nerves, but in the other organs of the body. Some zoologists have derived from this peculiarity, a name for the Division, sufficiently expressive, though too uncouth for general adoption, that of Heterogangliata. [1]

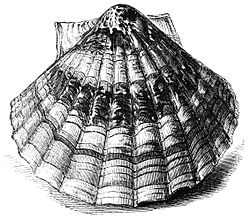

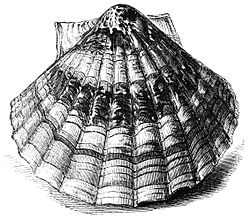

All the senses common to the higher animals are found in the Mollusca , though some are, doubtless, wanting in the humbler Classes of the Division. In the Cephalopoda, the organs of sight and hearing are distinct and well developed, and Professor Owen is of opinion that the Nautilus, an animal of this Class, possesses an organ of "passive smell." The are furnished with numerous eyes, placed among the tentacles, examples of which are found in the Clams and Scallops ( Pecten ) of our own shores. I scarcely know a more beautiful sight of the kind, than is presented by the edges of the mantle in one of our Scallops. If you ever have an opportunity of procuring a living specimen, which is not difficult to find at low water, on most of our rocky shores, place it in a glass of sea-water, and watch its movements. Soon the beautiful painted shells will begin to open, and the fleshy mantle will be seen to occupy the interval, like a narrow veil extending perpendicularly from each shell. The edge of each of these veils will now be seen, if you examine it with a pocket lens, to be fringed with long white threads, which are the tentacles, or organs of touch; and amongst them lie scattered a number of minute points, having the most brilliant lustre, and bearing a close resemblance to tiny gems. Indeed, the mantle has been aptly compared to one of those pincushions which are frequently made between pairs of these very shells, the eyes representing a double row of diamond-headed pins, set round the middle. It is observable that the Bivalves, which are thus profusely furnished with eyes, are also