The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by Marshall Editions

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33242-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-33256-7 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226332567.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

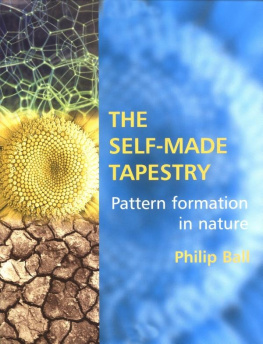

Ball, Philip, 1962 author.

Patterns in nature : why the natural world looks the way it does / Philip Ball.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-226-33242-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-33256-7 (e-book) 1. Pattern formation (Physical sciences) 2. Pattern formation (Biology) 3. Geometry in nature. 4. Nature. I. Title.

Q172.5.C45B357 2016

500.201'185dc23

2015034568

Conceived, edited, and designed by

Marshall Editions

The Old Brewery

6 Blundell Street

London N7 9BH

www.marshalleditions.com

QUAR. M PTN

Senior Editor: Chelsea Edwards

Senior Art Editor: Emma Clayton

Designer: Plum Partnership

Art Assistant: Martina Calvio

Copyeditor: Sarah Hoggett

Proofreader: Claire Waite Brown

Picture Researcher: Sarah Bell

Art Director: Caroline Guest

Creative Director: Moira Clinch

Publisher: Paul Carslake

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

The publishers will be grateful for any information that will assist them in keeping future editions up to date. Although all reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the publishers nor the authors can accept any liability for any consequence arising from the use thereof, or the information contained therein.

Color separation in Hong Kong by Cypress Colours (HK) Ltd

Printed in China by Hung Hing Off-set Printing Co. Ltd

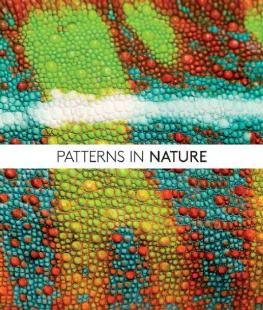

PATTERNS IN NATURE

WHY THE NATURAL WORLD LOOKS THE WAY IT DOES

Philip Ball

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

CONTENTS

Introduction

The world is a confusing and turbulent place, but we make sense of it by finding order. We notice the regular cycles of day and night, the waxing and waning of the moon and tides, and the recurrence of the seasons. We look for similarity, predictability, regularity: those have always been the guiding principles behind the emergence of science. We try to break down the complex profusion of nature into simple rules, to find order among what might at first look like chaos. This makes us all pattern seekers.

Its a habit hardwired into our brains. From a babys first inklings of repeated sounds and experiences, recognizing pattern and regularity helps us to survive and make our way in the world. Patterns are the daily bread of scientists, but anyone can appreciate them, and respond to them with delight and wonder as well as with aesthetic and intellectual satisfaction. Just about every culture on earth, from the ancient Egyptians to Native Americans and Australian Aborigines, has decorated its artifacts with regular patterns. It seems that we find these structures not only pleasing but also reassuring, as if they help us believe that, no matter what fate brings, there is a logic and order behind it all.

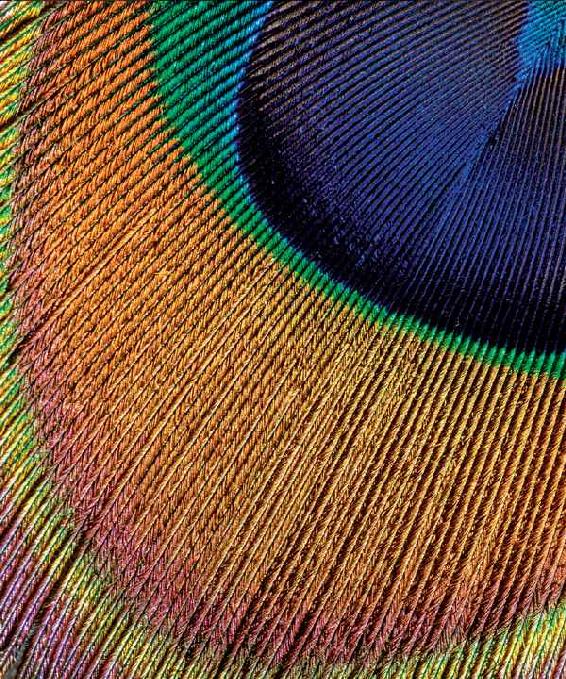

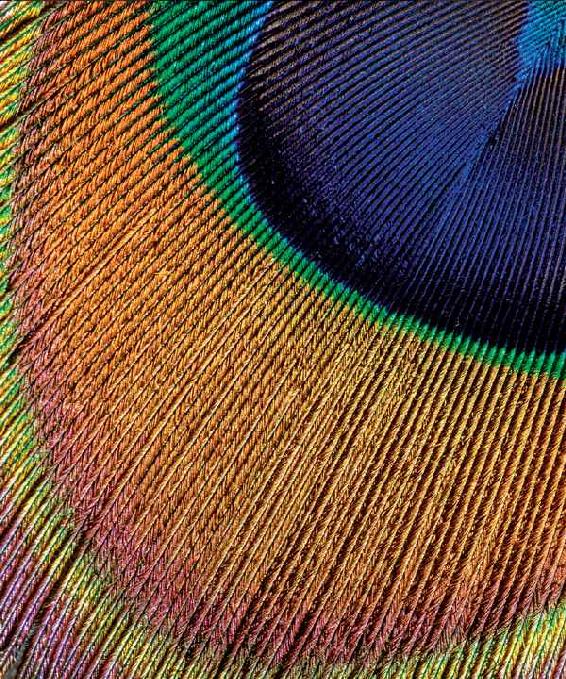

But when we make our own patterns, it is through careful planning and construction, with each individual element cut to shape and laid in place, or woven one at a time into the fabric. The message seems to be that making a pattern requires a patterner. Thats why, when people in former times recognized patterns in naturethe bees honeycomb, animal markings, the spiraling of seeds in a sunflower head, the six-pointed star of a snowflakethey imagined it to be the fingerprint of intelligent design, a sign left by some omnipotent creator in his handiwork.

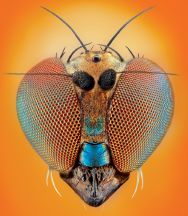

Today, we dont need that hypothesis. Its clear that pattern, regularity, and form can arise from the basic forces and principles of physics and chemistry, perhaps selected and refined by the exigencies of biological evolution. But that only deepens the mystery. How does the intricate tapestry of nature contrive to organize itself, producing a pattern without any blueprint or foresight? How do these patterns form spontaneously?

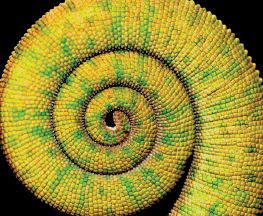

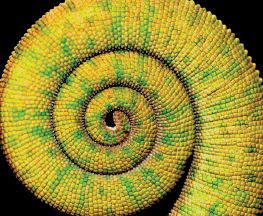

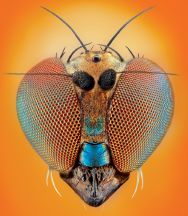

There are clues in how they look. Perhaps the most curious thing about natural patterns is that they come from a relatively limited palette, recurring at very different size scales and in systems that might seem to have nothing at all in common with one another. We see spirals, say, and hexagons, intricate branching forms of cracks and lightning, spots and stripes. It seems that there are types of pattern-forming process that dont depend on the detailed specifics of a system but can crop up across the board, even bridging effortlessly the living and the non-living worlds. In this sense, pattern formation is universal: it doesnt respect any of the normal boundaries that we tend to draw between different sciences or different types of phenomena.

Growth and form?

Do these patterns have anything in common, or is the similarity in their appearance just coincidence?

The first person to truly grapple with that question was the Scottish zoologist DArcy Wentworth Thompson. In 1917 Thompson published his masterpiece, On Growth and Form, which collected together all that was then known about pattern and form in nature in a stunning synthesis of biology, natural history, mathematics, physics, and engineering. As the title indicates, Thompson pointed out that, in biology at least, and often in the non-living world, pattern formation is not a static thing but arises from growth. Everything is what it is, he said, because it got that way. The answer to the riddle of pattern lies in how it got to be that wayhow the pattern grew. Thats less obvious than it sounds: a bridge or a paddy field or a microchip is explained by how it looks, not by how it was made.

Next page