Writing this book has often felt like a collaborative exercise, for which I am eager to spread some credit (while of course remaining accountable for all blame). For wise, perceptive, and tolerant suggestions and advice, and for the provision of materials and references, I am deeply indebted to many real experts in this arena, in particular Robert Axelrod, Robert Axtell, Albert-Laszl Barabsi, Eshel Ben-Jacob, Rama Cont, Dirk Helbing, Steve Keen, Thomas Lux, Mitsugu Matsushita, Joe McCauley, Mark Newman, Paul Ormerod, Craig Reynolds, Sorin Solomon, Gene Stanley, Alessandro Vespignani and Tams Vicsek. The support of my editors, John Glusman, Ravi Mirchandani, and Caroline Knight, has been vital, and many rough edges were knocked off the text by the careful attention of the copy editor, John Woodruff. I have been encouraged as ever by the good judgment of my agent, Peter Robinson, and the support of my wife, Julia.

Philip Ball

London, October 2003

Designing the Molecular World:

Chemistry at the Frontier

Made to Measure:

New Materials for the 21st Century

The Self-Made Tapestry:

Pattern Formation in Nature

Lifes Matrix:

A Biography of Water

Stories of the Invisible:

A Guided Tour of Molecules

Bright Earth:

Art and the Invention of Color

The Ingredients:

A Guided Tour of the Elements

The Devils Doctor:

Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science

T he performer who provides his own applause is surely either deluded or desperate; but where better than in conclusion to describe the following delightful manifestation of social physics?

In some countries and cultures, particularly in Eastern Europe, the applause with which a gratified audience expresses its appreciation of a performance tends to slew back and forth between random and synchronized. At one moment each person is clapping to his or her own rhythm, and the hundreds of overlapping pulses of sound create a continuous clattering roar like the sound of surf on shingle. But then something remarkable happens: this wash of noise resolves itself into a regular beat, as each pair of hands claps in unison with the others. The synchronization lasts for perhaps a minute or so, then dissolves again into chaos.

There is no one conducting this performance, no one to set the pace or to signal when synchrony should begin. It just happensnot once but several times during an ovation. Now, it is no great feat for two or three people to bring their hand claps into step with one another. Indeed, it can be hard for them to avoid doing so, just as two people tend to synchronize their steps when they walk side by side. But the synchronized clapping of an audience of many hundreds is a challenge of another order. That it can crystallize so quickly is surprising enough: but why, once synchronized, does the clapping not stay that way, given that each member of the audience can consciously sustain it with little effort? Why this seesawing alternation between order and chaos?

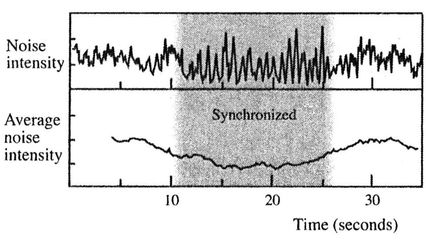

Tams Vicsek, Albert-Lszl Barabsi, and their co-workers have asked this same question. They made sound recordings of the postperformance applausein several theaters and opera halls in Hungary and Romania, and looked at how the sound volume changed as clapping veered between incoherent and synchronized. They found that although synchronized clapping produces spikes of noise that can exceed the sound level during incoherent clapping, nevertheless synchronization decreases the average noise intensity in the hall (Figure E.1).

This decrease happens not because the audience members are clapping any less vigorously when they are in step, but because they clap less often. People space their claps roughly twice as far apart in the synchronized mode than when clapping freely. This is presumably because it is harder to clap in time with everyone else if the rhythm is too fastsynchronization of a slow hand clap disintegrates if the pace quickens. No one in the audience thinks consciously about this; the measured rhythm of the synchronized clap essentially selects itself.

The researchers suggest that the difference in average sound volume explains why applause at concerts oscillates between incoherent and synchronized. An appreciative audience wants to make a lot of noise. It also appears to enjoy the communal experience of synchronized clapping, which lends the crowd a single voice. But these two things are in conflict, because synchronization results in a drop in the average noise intensity. No one registers this drop consciously; but the audience, having switched into synchronized mode, nonetheless begins to speed up the rhythm so as to restore the sound volume to its earlier, unsynchronized level. In doing so, they lose the ability to keep their claps in step, and the sychronization dissolves into incoherence. Moments later, the attractive tug of synchrony reasserts itself and the cycle repeats.

E.1 Sound levels during audience applause in an Eastern European theater. The switch from random to synchronized clapping is marked by the appearance of sharp, regularly spaced peaks in the noise intensity (top). When this happens, the average noise intensity diminishes (bottom), only to rise again as the synchronized clapping dissolves.

A push and a pull; a tension between conflicting desires. This is all it takes to tip our social behavior into complex and often unpredictable, patterns, dictated by influences beyond our immediate experience or our ability to control. Regardless of what we believe about the motivations for individual behavior, once we become part of a group we cannot be sure what to expect.

INTRODUCTION: POLITICAL ARITHMETICK

W. Petty (1690). Political Arithmetick. Robert Clavel, London.

Ibid.. Preface.

K. Waltz (1954). Man, the State, and War , p. 75. Columbia University Press, New York.

CHAPTER 1: RAISING LEVIATHAN

EPIGRAPHS

Bernard Fontenelle, quoted in A.G.R. Smith (1972). Science and Society in the 16th and 17th Centuries, p. 153. Science History Publications. New York.

Bernard Fontenelle (1686). Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, trans. W. Gardiner (1715), pp. 1112. London.

Robert M. Maclver (1947). The Web of Government . Macmillan. New York. Quoted in R. Bier stedt, ed. (1959). The Making of Society, p. 493. Random House, New York.

Stephen Cutgrove (1967). The Science of Society, p. 181. Allen & Unwin, London.

Snorri Sturluson (thirteenth century). The Prose Edda, trans. J. I. Young (1964) (with minor changes).p.86.University of California Press, Berkeley.

J. Aubrey (1681). Brief Lives, ed. J. Buchanan-Brown (2000). pp. 427-28. Penguin. London.

T. Hobbes (1651). Leviathan, ed. C. B. Macpherson (1985), pp. 11011. Penguin, London.