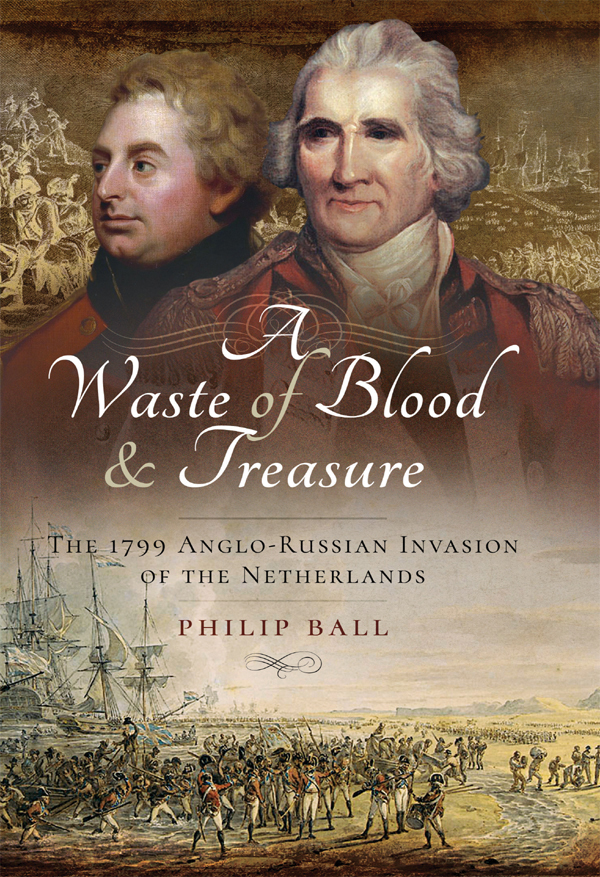

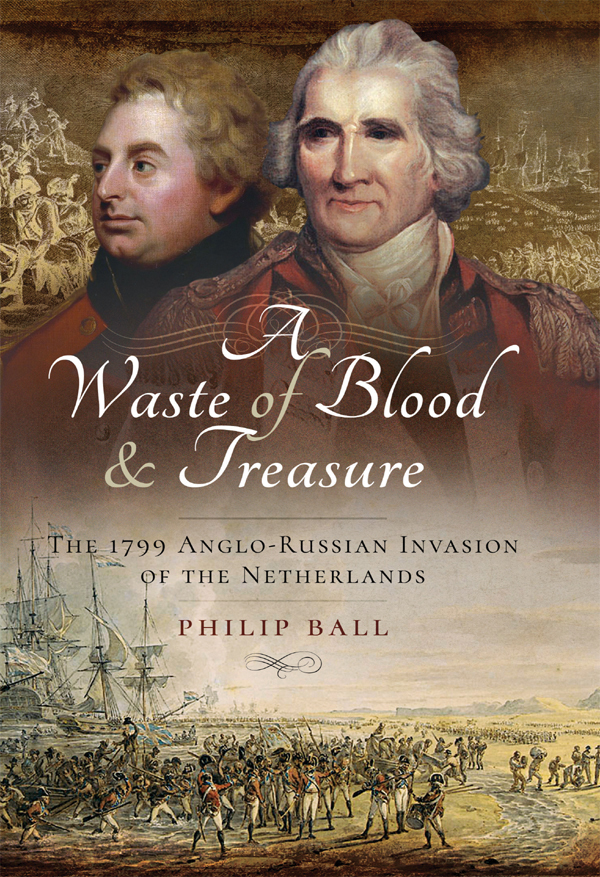

A Waste of Blood and Treasure

A Waste of Blood and Treasure

The 1799 Anglo-Russian Invasion of the Netherlands

Philip Ball

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Philip Ball, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47388 518 9

eISBN 978 1 47388 520 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 519 6

The right of Philip Ball to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Maps

The Helder

The landing at Callantsoog

The Battle of Krabbendam, showing the Franco-Batavian attack and the British position on the Zype Canal

The Battle of Bergen

The Battle of Egmond

The Battle of Castricum

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the numerous individuals who have given their time and lent their expertise to the production of this book. Firstly I must acknowledge the assistance of Doctor Jacqueline Reiter without whom this work would never have seen the light of day. I would also like to recognize the contribution of John Harcourt who worked so hard to translate my rough sketches into splendid maps and Romain Cames who translated Milyutins history of the campaign from the original Russian. Finally I give thanks to my partner Tracy and my parents who helped to ensure the text was readable and all my friends and colleagues who have endured my obsession with this campaign over the last few years.

Introduction

T he winter of 1795 had been especially harsh. The canals and ditches of Holland had frozen, compounding the misery of the Duke of Yorks broken army as they limped their way towards Bremen and their ships home. However, it was these same conditions that enabled the French Army under General Pichegru to surge across Holland. The natural defences of their country nullified by the winter ice meant the Dutch were unable to repel them. Resistance was quickly crushed and the Dutch ruler, the Prince of Orange, was forced to flee to Britain. The Netherlands became a satellite of the French Republic.

The Dutch had been a reluctant ally; British sources are replete with accounts of the unreliability of their troops and the hostility of their citizens but now they had become the Batavian Republic and an active foe. This was particularly galling to the British Government as not only had they entered the First Coalition, at least in part to protect the Dutch from French aggression, but the powerful Dutch fleet could now undermine the Royal Navys hard-earned supremacy in the North Sea. Whilst this particular threat was diminished somewhat by Admiral Duncans victory at Camperduin in 1797, the existence of the Batavian Republic remained a thorn in the side of the British administration, an affront to Britains prestige and a reminder of their failure.

The United Provinces of the Netherlands was a peculiar political entity. Established by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1579, it was a loose federation of seven sovereign provinces, each of which sent representatives to the States-General who made the laws and ruled the country. Politics within this republic had been, from the start, defined by the struggle between the interests of the merchant classes, who through the wealth of the province of Holland (which accounted for sixty per cent of the Netherlands total revenue) were able to occupy a position of dominance, and the supporters of the princes of Orange who sought to transform their hereditary role as figure head and military commander into something like the royal power enjoyed by the princes of neighbouring states.

There had been a revolution in 1787 by middle class liberals (the Patriots) seeking to limit the power of the Stadholder and bring liberty to the people. It had been crushed by the intervention of the Prussian Army under the Duke of Brunswick in extremely short order but the Patriots had merely gone to ground hoping for another opportunity to take power. The revolution in France had given many of them fresh hope and the forces that invaded the Netherlands in 1795 included a Batavian Legion of troops raised and led by Patriots from exile in France.

There seems to be little indication that the ordinary Dutch were particularly thrilled about the institution of the Batavian Republic. Certainly they exhibited little enthusiasm for the allied cause in the war against France but to what extent this translated into wholesale republicanism is debatable. Support for the House of Orange had been traditionally strong amongst the poorer elements of Dutch society (the grauw ) but this was at a low ebb by 1795, and certainly few seemed sorry to see the prince leave. These measures were the cause of much resentment and Orangist agents found evidence of anti-French sentiment as they spied on their former state, but to what extent the people of the Netherlands were poised to rise in revolt to restore their prince remained to be seen. Certainly the Prince of Orange and his supporters believed that they would, and began to lobby the British Government for assistance.

The arguments put forward by the prince and his party were persuasive and backed by considerable intelligence so perhaps, when taken alongside the humiliation felt by Britain over the loss of their erstwhile ally, it is easy to see why these arguments found a sympathetic audience.

Britain was a maritime power and, apart from the Duke of Yorks ill-fated expedition to Flanders between 1793 and 1795, its efforts in the war up to this point had been restricted to snapping up isolated French colonies and launching limited coastal raids. As the MP and playwright Richard Sheridan put it, they had merely nibbled the rind of France. A party had emerged in the cabinet, which was intent on carrying the war onto the continent and its leader, William, Lord Grenville, was one of those listening closely to the Orangists arguments. Grenville was foreign secretary and was close to Prime Minister William Pitt (in fact they were cousins) and he believed that liberating the Netherlands would not only restore Britains tarnished prestige and strike a major blow against France but it would also open up the possibility for a wide range of other strategic options. Grenville felt that if the war was to be won there had to be an all out co-ordinated effort on the continent. He thought that action in the Netherlands would bring Prussia back into the war as Britains ally, that a popular rising there would spark others and that these could be supported by the British Army operating on the continent, and finally that they would be able to act with the hitherto victorious Austro-Russian forces now sweeping through Italy towards Switzerland.

Next page