CONTENTS

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower

22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor

Toronto, ON, M5H 4E3, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

India

HarperCollins India

A 75, Sector 57

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201 301, India

http://www.harpercollins.co.in

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

http://www.harpercollins.com

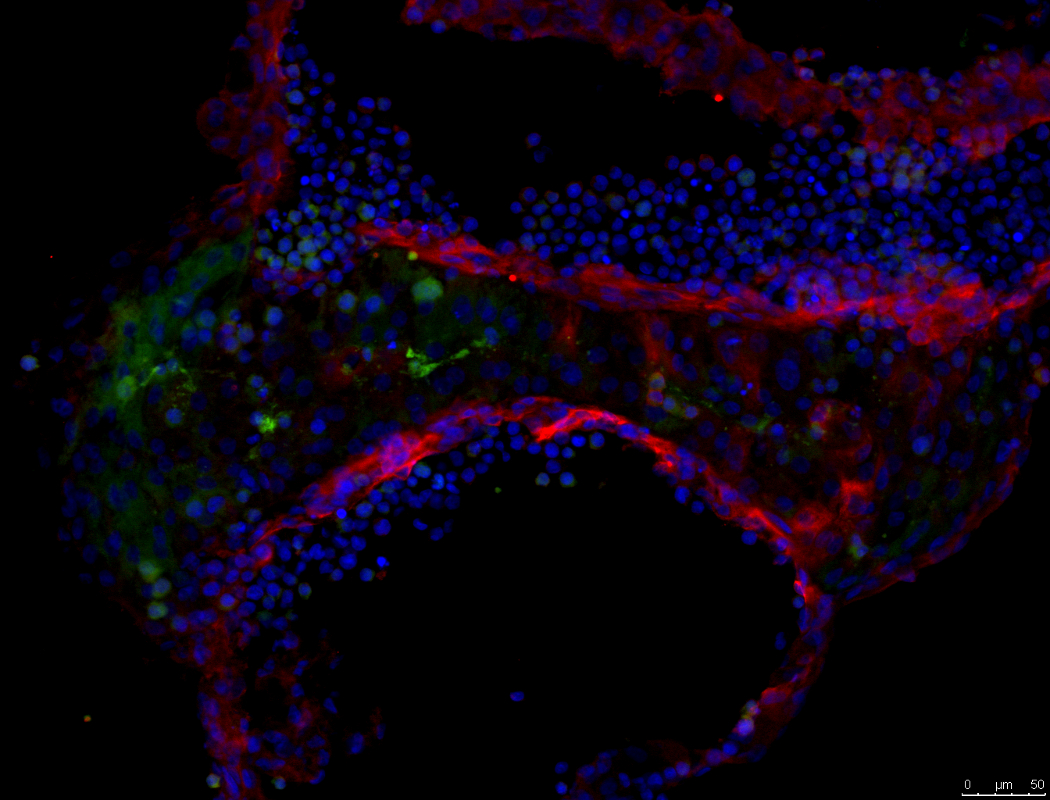

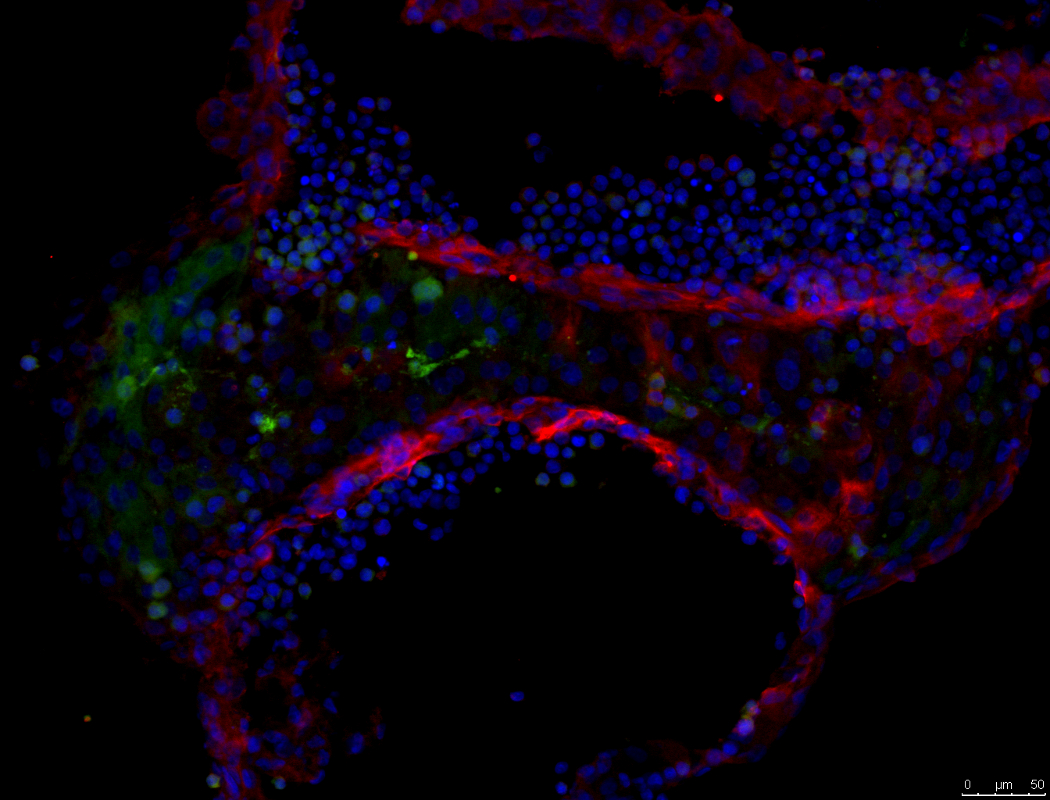

After seeing his own cells used to grow clumps of new neurons essentially mini-brains Philip Ball begins to examine the concepts of identity and consciousness. Delving into humanitys deep evolutionary past to look at how complex creatures like us emerged from single-celled life, he offers a new perspective on how humans think about ourselves.

In an age when we are increasingly encouraged to regard the self as an abstract sequence of genetic information, or as a pattern of neural activity that might be downloaded to a computer, he return us to the body to flesh and blood and anchors a conception of personhood in this unique and ephemeral mortal coil. How to Build a Human brings us back to ourselves but in doing so, it challenges old preconceptions and values. It asks us to rethink how we exist in the world.

This book would not have been possible without might often seem like a piece of formulaic hyperbole, but it is certainly not in this case. I can safely say that I could not myself have grown a brain organoid from a piece of my arm, and until I first met Selina Wray of University College London I didnt even know it was possible. She and Chris Lovejoy have been immensely supportive, welcoming and generous in sharing their knowledge and skills about this astonishing process, and I am deeply grateful to them for starting me on the journey.

The impetus for the Brains in the Dish project came from artist Charlie Murphy, whose energy and imagination helped to see it through. Charlies own responses to the experience, rendered mostly in glass objects of great delicacy and beauty, are inspiring. Thanks also to Ross Paterson for doing the dirty (in fact, of course, clinically clean) work of taking the biopsy.

Theres also a without whom element to the broader story. It was a huge pleasure and honour to be involved in Created Out of Mind, the residency at the Hub in the Wellcome Collection, London, for 201618. That ambitious project was led, with tremendous flair, patience, vision and good humour, by Seb Crutch of UCL, to whom I am full of gratitude for inviting me to be a part of the team working to change perceptions of dementia and to improve the lives and the care of people living with it. That team was a joy to work with, and included Caroline Evans, Kailey Nolan, Emilie Brotherhood, Janette Junghaus, Harriet Martin, Julian West, Paul Camic, Fergus Walsh, Nick Fox, Gill Windle, Susanna Howard, Charlie Harrison, Hannah Zeilig, Millie van der Byl Williams, Tony Woods, Bridie Rollins and, oh goodness, I have probably forgotten others I should mention or who I never managed to meet, for which I ask their forgiveness.

I received advice from many experts in the course of preparing this book, as well as in writing some of the articles that informed it. Sometimes they will not have known (as I did not then know) that this is where their knowledge and wisdom would end up. Others kindly agreed to look at parts of the text and put right what I had wrong. Others supplied important materials for the research. They include Kristin Baldwin, Buzz Baum, Martin Birchall, Ali Brivanlou, Dan Davis, Sarah Franklin, Hank Greely, Ronald Green, Allon Klein, Christof Koch, Madeline Lancaster, Jennifer Lewis, Alison Murdoch, Werner Neuhausser, Brigitte Nerlich, Kathy Niakan, Andrew Reynolds, Adam Rutherford, Mitinori Saitou, Anil Seth, Marta Shahbazi, Deepak Srivastava, Azim Surani and Joseph Vacanti. Once again they have reminded me of how generous busy scientists and writers almost invariably are.

My editors in the UK and USA have given consistently smart advice, for which I owe many thanks to Hazel Eriksson, Myles Archibald and Karen Merikangas Darling. Karen obtained some thoughtful and helpful reviews whose anonymous authors I thank too. And Im not sure what I would do without the support, encouragement and belief of my agent Clare Alexander, but it would probably involve finding another line of work.

Frankly, were living through some grim times. The research and ideas I describe in this book create some alarming and disturbing possibilities, but they also speak to me of the determination of many folks to try to make things better, and of their ingenuity in that quest. Its never felt more vital, though, to receive support, companionship and love from my friends and family. Im lucky to have that, and I am thankful.

Philip Ball

London, 2018

Ex ovo omnia.

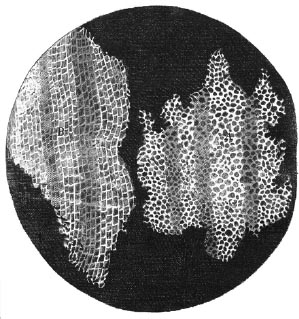

So declared the frontispiece of Exercitationes de generatione animalium (1651) by the seventeenth-century English physician William Harvey, sometime physician to James I. It expressed a conviction (and no more) that all things living come from an egg.

William Harveys motto All things from an egg in the frontispiece of his 1651 treatise on the generation of animals.

Its not really true: plenty of living organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, do not begin this way. But we do. (At least, we have done so far. I no longer take it for granted that this will always be the case.)

Egg is an odd term for our generative particle, and indeed Harvey was a little vague about what he meant by it. Strictly speaking, an egg is just the vessel that contains the fertilized cell, the zygote in which the male genes from sperm are combined with the female genes from the egg cell or ovum. Yet its easy to overlook how bold a proposal Harvey was making, in a time when no one (himself included) had ever seen a human ovum and the notion that people might begin in a process akin to that of birds and amphibians could have sounded bizarre.

The truth of Harveys insight could only be discerned once biology acquired the idea of the cell, the fundamental atom of biology. That insight is often attributed to Harveys compatriot and near-contemporary Robert Hooke, who made the most productive use of the newly invented microscope in the 1660s and 70s. Hooke discerned that a thin slice of cork was composed of tiny compartments that he called cells. This is often said to be an allusion to the cloistered chambers (Latin cella: small room) of monks, but Hooke drew a parallel instead with the chambers of the bees honeycomb, which in turn probably derive from the monastic analogy.

Next page