Philip Ball - The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science

Here you can read online Philip Ball - The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: MIT Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science

- Author:

- Publisher:MIT Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- APPENDIX

2020 Philip Ball and Xinzhi Digital Media

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Helvetica and Gotham by the MIT Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-04441-7

10987654321

d_r0

ELEMENTAL: THE CHARISMA OF CHEMISTRY

Chemistry, more than any other science, is a confluence of the practical and the sublime. It's best known in the first of these guises: as the prosaic source of the substances all around us, by which our lives are increasingly shaped for better or worse. We are apt, like ungrateful children, to take for granted the dyes that clothe us in fashionable and flattering shades, the artificial scents that hide our own, the medicines that relieve our aches and ailments, the tiny slices of high-tech semiconducting alloys in our smartphones. We grumble (and so we should, although not at chemistry) about the pollutants in our air and water, the plastics clogging our rivers and seas. Chemistry gives us the fabrics of our existence: polyesters and polycarbonates, touchscreens and batteries, non-stick pans and non-drip paint. We depend on its bounty but fear its baneful influence: it is both problem and cure, nemesis and savior.

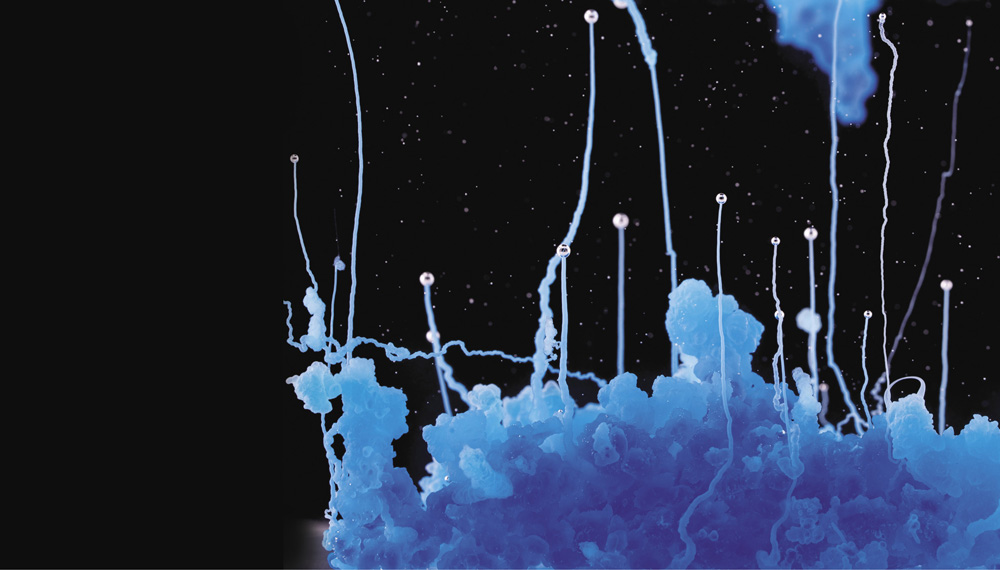

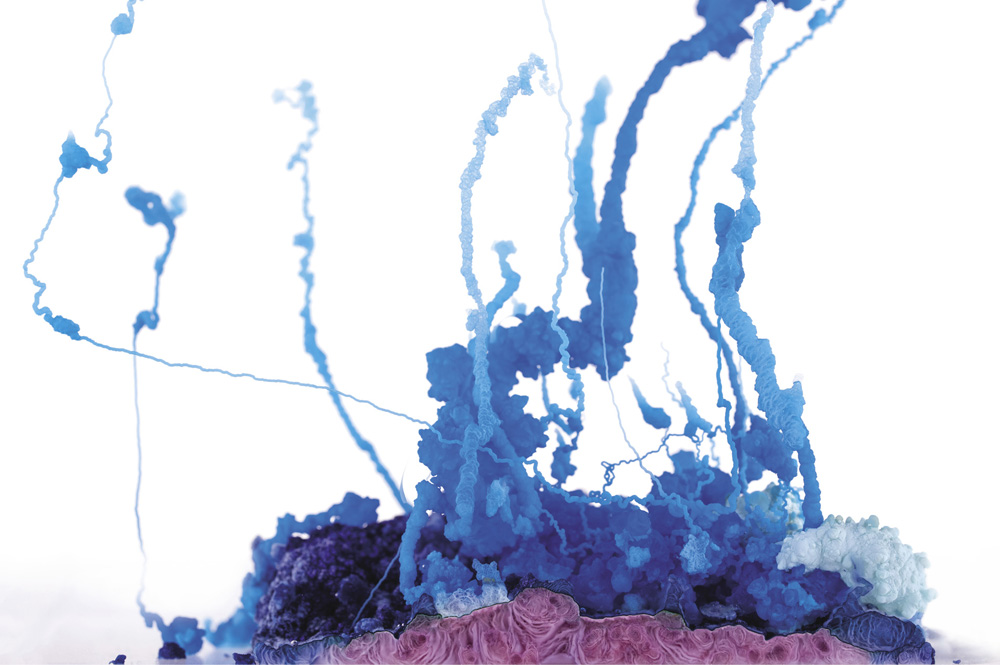

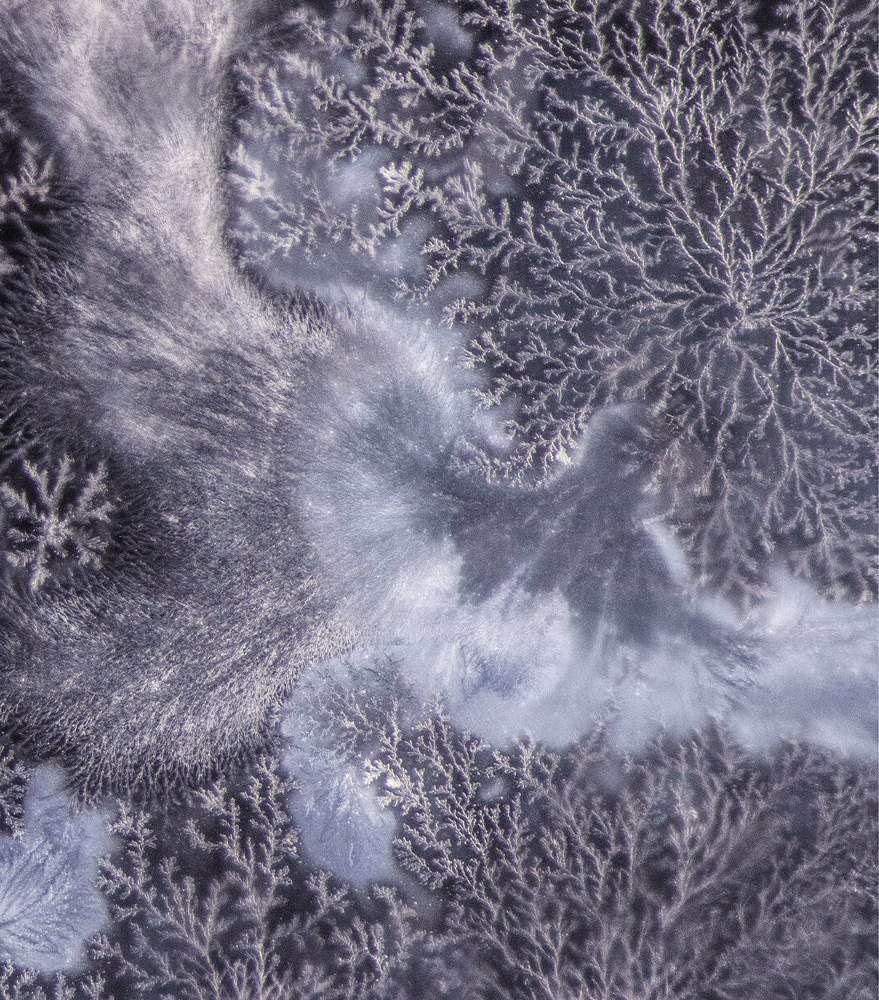

The chemical sublime is less familiar, but this book will introduce you to it. We will show some of the astonishing beauty that resides in chemical products and processes. This beauty too often passes unseen, or at least unacknowledged as chemical in nature. We can marvel at the delicacy of a snowflake, or the glory of a flower and its heady fragrance, while failing to realize that chemistry is at work here every bit as much as it is in oil refineries and pharmaceutical plants.

There doesn't seem to be a word for people who take delight in stuff, but there ought to be. We propose that they be called ousiophiles, from the Greek ousia, meaning essence or substance. Chemists are usually ousiophiles: they delight in tangible material, in texture and heft, in luster and pliancy. They want to touch and feel things, to smell and taste them. It's in this impulse that a love of chemistry resides; people who have it are often drawn to study the subject.

The Italian writer Primo Levi was undoubtedly an ousiophile. Levi wrote two particularly famous books, and one of them was The Periodic Table, a love letter to the primal substances, the elements, of chemistry. The book's title alludes to the iconic scheme used to arrange the chemical elements and which reveals the hidden order among them. Each chapter of Levi's book is named after a chemical elementargon, hydrogen, zinc, iron, potassium, and moreand makes its titular substance a character in a story, generally drawn from an episode in Levi's life. He revels in the materiality of these substances: chromium, mixed into an orange anti-rust paint in the factory outside Turin where Levi worked after the Second World War, or the generous good nature of tin, Jove's metal. The Periodic Table brought a chemical sensibility to the notice of readers who might have remembered nothing from their school chemistry lessons, not even the blocky format of the periodic table itself.

Levi's other famous book is If This Is a Man, an account of the time he spent in the concentration camp at Auschwitz. There his knowledge of chemistry saved his life by making him eligible to work in the laboratory that served the Buna industrial plant, set up to make artificial rubber for the Nazi war effort. If it had not been for that assignment, it is unlikely Levi would have survived in Auschwitz during the harsh winter of 1944. Because he did, the world got to see this vital, harrowing, deeply humane account of atrocity.

To some chemists, the periodic table has almost the status of a catechism. Within its rows and columns of elemental symbols is encrypted much of what chemistry is about. It's not just that these elements are the building blocks of the subject, the varieties of atom from which all the physical world is constructed. The shape and topography of the table, gathering together elements with shared chemical properties, reflect the principles that govern atomic unions, dictating how elements may be combined to produce all the beauty and richness, the hazards and surprises, of the chemical world. To the initiated, the location of carbon (say) hints at its role in living things, while it is because the alkali metals come first in each row of the table that the chemist knows they will be highly reactive, dangerous to the touch. By the same token, by ending each row the inert gases such as xenon and argon are granted their lack of reactivity. Levi used them as metaphors for the character of the Jews of Turin from whom he was descended, alluding to their attitude of dignified abstention.

The periodic table was internationally celebrated in 2019 to mark the 150th anniversary of its first appearance. (By coincidence this was also the centenary of Primo Levi's birth.) In 1869 an early version of the table, sketchy and full of gaps, was unveiled by the Siberian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. He was by no means the first to recognize that the chemical elements can be grouped into families in which all the members show similar behavior. And if Mendeleev had not discerned the way these groups fit together, others would surely have done so around the same time. But Mendeleev was almost alone in trusting this deep structure enough to leave gaps where he figured new elements, as yet undiscovered, should exist. Those gaps were filled in due course, and Mendeleev's predictions about the properties of these missing elements were borne out.

The periodic table of the chemical elements doesn't self-evidently deserve the reverence that many chemists seem to feel for it. It's not a terribly elegant structure. With its rows of elements rising to turret-like peaks at either end and the long block of elements (called the transition metals) in the middle, the shape resembles a somewhat ungainly modernist housing development. Besides, chemists aren't even agreed today on exactly how the table should be drawn; there are still disputes about where some of the elements should be placed.

All the same, the recognition of this hidden order among the profusion of elements implied that there are deeper principles that determine their chemical properties. It took a further half-century after Mendeleev's publication to figure out what these principles are.

A key part of that puzzle was supplied in 1916 by the American chemist Gilbert Lewis, who argued that the chemical properties of the elements could be understood from the nature of the atoms of which they are composed. In the early years of the twentieth century, scientists discovered that atoms are not dense, featureless little balls of matter as had once been supposed, but have some internal structure composed from yet more fundamental particles. They have a very dense nucleus, which has a positive electrical charge and contains particles called protons (and also electrically neutral particles called neutrons, not discovered until 1932). Around the nucleus are arrayed much lighter particles called electrons, which have a charge equal in size but opposite in sign to that of the proton. Most of the atom is empty space; in one of the earliest pictures they were envisioned as tiny solar systems, with the nucleus as a kind of sun orbited by planetary electrons. This is too simplistic an image, but it was good enough to be useful for understanding how atoms of matter are constituted.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science»

Look at similar books to The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Beauty of Chemistry: Art, Wonder, and Science and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.