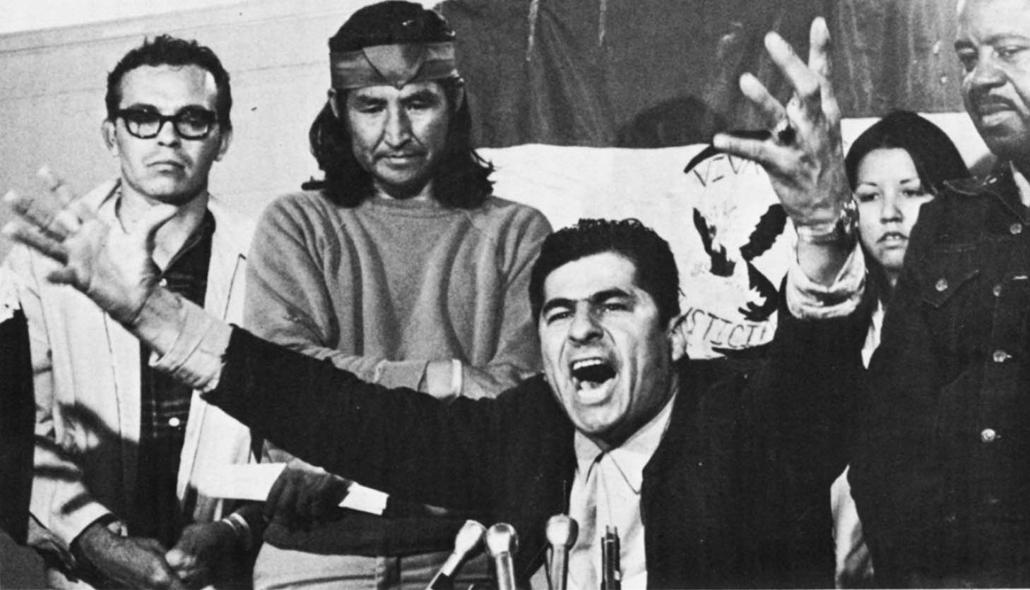

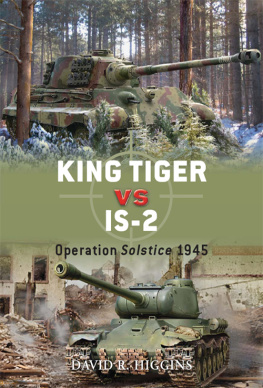

KING TIGERFRONTISPIECE: Reies Tijerina at the Poor Peoples March, Washington, D.C., 1968. At the left: Hank Adams and Al Bridges, Indian leaders. At the right: Rev. Ralph Abernathy. Source: Patricia Bell Blawis, Tijerina and the Land Grants (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 164.

KING TIGER

The Religious Vision of Reies Lpez Tijerina

Rudy V.Busto

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8263-2791-8

2005 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2005

Printed in the United States of America

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Busto, Rudy V., 1957

King Tiger : the religious vision of Reies Lpez Tijerina / Rudy V. Busto.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8263-2789-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Tijerina, ReiesPolitical and social views. 2. Tijerina, ReiesReligion. 3. Mexican AmericansLand tenureNew MexicoHistory20th century. 4. Mexican AmericansNew MexicoEconomic conditions20th century. 5. Land tenureNew MexicoHistory20th century. 6. Civil rights workersNew MexicoBiography. 7. Mexican AmericansNew MexicoBiography. 8. Civil rights movementsNew MexicoHistory20th century. I. Title.

f805.m5t5415 2005

978.90046873dc22

2005022333

Design and composition: Melissa Tandysh

For my mother, Socorro Busto-Hiatt

And to the memory of my father,

Valeriano Ramos Busto

CONTENTS

Valle de Paz:

Texts, Visions, and Landscapes |

Mi lucha por la tierra:

A Struggle for Voice |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are many people who helped this project come into being. Chief among them, of course, is Reies Tijerina. Reiess patience and long-suffering with a new generation of academics has been my boon. Although I do not expect him to agree with everything I have written here, my best hope is that he would find that I have tried to represent his life and work with respect and care. My fascination and awe with Tijerina verges on what scholars of religion call tremendum et fascinans.

The earliest support for this project came from my graduate advisor, Margarita Melville, who understood the power of religious conviction and its political consequences, and thus why writing about Tijerina was a good idea. My appreciation for her support and example of passionate scholarship only increases over time.

Others crucial to the shaping and organization of my ideas for this book beyond the dissertation include Susana Gallardo, Gastn Espinosa, Alberto Pulido, and Daniel Ramrez. Assistance from Stanford undergraduates Noah Rodrguez and Tanya Moreno in the form of library research is gratefully acknowledged. Friends and colleagues involved in the Hispanic Theological Initiative (HTI) have offered me moral support, as have Alice Bach, Davd Carrasco, James Treat, Randi Walker, Gilbert and Renya Ramrez, Jennifer Michael, Priya Karim Haji, and Tony Stevens-Arroyo. Tangible support by way of specific information and assistance is gratefully acknowledged from Jay Maiorana, Mario Garcia, Andrs Guerrero, Peter Nabokov, Carlos Muoz, Jr., Jorge Bustamante, Claude Clegg III, Amado Padilla, Evangeline Corona, drafting supervisor for the Pinal County Assessors Office, Julie Hoff of the Arizona Capitol Library, Baptist historian, Bill Hunke, the staff at the Zimmerman Library (UNM), and numerous nuevomexicanos who smoothed my path at every turn in my research. Although I never knew him personally outside of a brief correspondence, an enormous debt is owed to the late Clark S. Knowlton, whose long view of Tijerina and the Alianza resulted in a valuable corpus of writing crucial to understanding Tijerina and his context.

Despite the assistance of all of these scholars upon whose work this book depends, I need only add that responsibility for the interpretation put forth, as well as any errors and omissions, is mine alone.

I am forever grateful to my family for all of their love and support, especially to my mother, Socorro Busto-Hiatt, for her unending prayers and instilling in her children the love of books and insisting on the power of Philippians 4:13. A large measure of love and gratitude is reserved for Tony Feudo and Maria Elizabeth Carlotta Feudo, who continually remind me of the priorities in this life, encourage me, and make it worth the effort. I acknowledge my cat, Puss Puss, the only sentient being who truly knows all that this project required.

The process of putting this book together has been lengthy, and so I owe a great debt of gratitude to David Holtby and Maya Allen-Gallegos of the University of New Mexico Press for their forbearance and oversight.

TERMS

The term Mexican American is used to refer to persons of Mexican descent living in the United States since the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. It is also used to refer to Mexican descent Americans prior to the 1960s adoption of the ethnopolitical term Chicano. Mexican is used to denote nationality and as descriptive of cultures and traditions originating in Mexico (e.g., Mexican Catholicism). Chicano is used to describe the progressive, sometimes radical assertion of ethnic and political identity, particularly by young Mexican Americans beginning in the mid-1960s, and then as descriptive of the culture and scholarship arising out of the Chicano Movement (e.g., Chicano history). The term Hispanic is for the most part avoided, but used to describe the leveling of Spanish-speaking Americans by the federal government in the 1980s. Among Chicanos it is a derogatory term. On the other hand, Latino is the commonly accepted label encompassing the larger population of Spanish-speakers in the United States.

Regional Mexican Americans have their own labeling traditions, and so I use Hispano to indicate the people and cultures associated with the traditions specific to Spanish-speaking New Mexicans reaching back to the Spanish settlements in the sixteenth century. Similarly, I employ the local colloquialism, vecino (literally, neighbor) and nuevomexicano or Nuevo Mexicano to refer to land grant heirs in northern New Mexico. Spanish American is an older regional ethnic term constructed around the history and continuation of the earliest Spanish arrival into what is now New Mexico and southern Colorado at the end of the sixteenth century. Tejano refers to Mexican Americans from Texas. Anglo is an awkward but common label used historically by Mexican Americans and Chicanos to refer to all European Americans. Clearly these are cultural and political labels more than they are racial ones.

The term evangelical is used as an umbrella term to denote a distinct theological worldview. Broadly speaking it includes traditions that subscribe to a literalist interpretation of the Bible, the intense experience of born again conversion, active missionary efforts, and the expectation that Jesus will physically return at a future date to gather up the saved. Fundamentalism refers to a harsher, ethically stringent and uncompromising form of evangelical belief and practice.