Brandeis Series on Gender, Culture, Religion, and Law

SERIES EDITORS: LISA FISHBAYN JOFFE AND SYLVIA NEIL

This series focuses on the conflict between womens claims to gender equality and legal norms justified in terms of religious and cultural traditions. It seeks work that develops new theoretical tools for conceptualizing feminist projects for transforming the interpretation and justification of religious law, examines the interaction or application of civil law or remedies to gender issues in a religious context, and engages in analysis of conflicts over gender and culture/religion in a particular religious legal tradition, cultural community, or nation. Created under the auspices of the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute in conjunction with its Project on Gender, Culture, Religion, and the Law, this series emphasizes cross-cultural and interdisciplinary scholarship concerning Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and other religious traditions.

For a complete list of books that are available in the series, visit www.upne.com

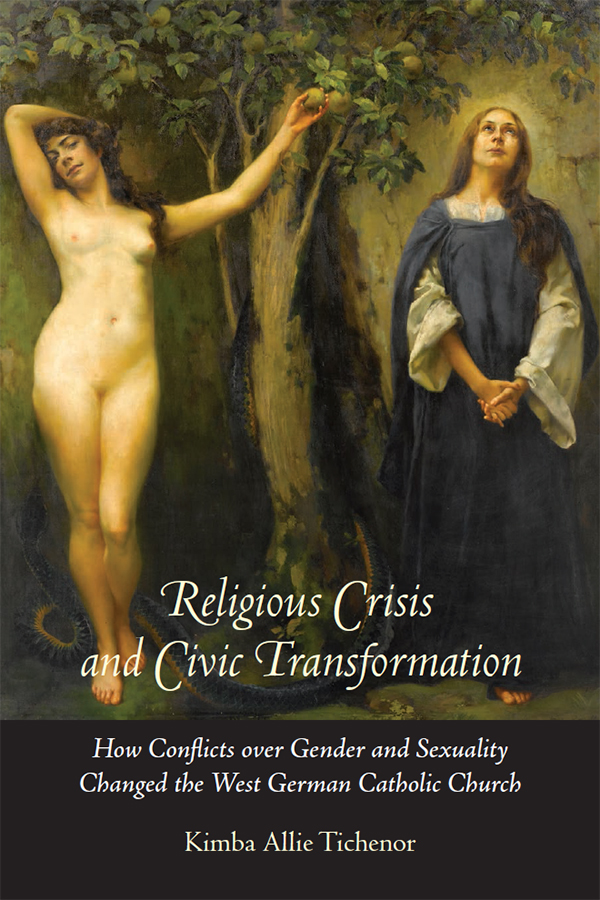

Kimba Allie Tichenor, Religious Crisis and Civic Transformation: How Conflicts over Gender and Sexuality Changed the West German Catholic Church

Margalit Shilo, Girls of Liberty: The Struggle for Suffrage in Mandatory Palestine

Mark Goldfeder, Legalizing Plural Marriage: The Next Frontier in Family Law

Susan M. Weiss and Netty C. Gross-Horowitz, Marriage and Divorce in the Jewish State: Israels Civil War

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe and Sylvia Neil, editors, Gender, Religion, and Family Law: Theorizing Conflicts between Womens Rights and Cultural Traditions

Chitra Raghavan and James P. Levine, editors, Self-Determination and Womens Rights in Muslim Societies

Janet Bennion, Polygamy in Primetime: Media, Gender, and Politics in Mormon Fundamentalism

Ronit Irshai, Fertility and Jewish Law: Feminist Perspectives on Orthodox Responsa Literature

Jan Feldman, Citizenship, Faith, and Feminism: Jewish and Muslim Women Reclaim Their Rights

R eligious C risis and C ivic T ransformation

How Conflicts over Gender and Sexuality Changed the West German Catholic Church

KIMBA ALLIE TICHENOR

Brandeis University Press

WALTHAM, MASSACHUSETTS

Brandeis University Press

An imprint of University Press of New England

www.upne.com

2016 Brandeis University

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tichenor, Kimba Allie, 1959 author.

Title: Religious crisis and civic transformation: how conflicts over gender and sexuality changed the West German Catholic Church / Kimba Allie Tichenor.

Description: Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2016. | Series: Brandeis Series on gender, culture, religion, and law | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015040835 (print) | LCCN 2015040190 (ebook) | ISBN 9781611689709 (epub, mobi & pdf) | ISBN 9781611689082 (cloth) | ISBN 9781611689099 (paper)

Subjects: LCSH: SexReligious aspectsCatholic Church. | CelibacyCatholic Church. | Gender identityReligious aspectsCatholic Church. | Religion and civil societyGermany (West) | Catholic ChurchGermany (West) Classification: LCC BX1795.S48 (print) | LCC BX1795.S48 T534 2016 (ebook) | DDC 282/.4308109045dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040835

Contents

Foreword

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe

Kimba Allie Tichenor notes that the challenge of reconciling womens rights and religious law is often raised in discussions of Islam in Europe but is rarely explored in connection with Christian denominations. The Brandeis Series on Gender, Culture, Religion, and Law is committed to publishing work that deepens our understanding of the dynamics surrounding womens struggle for gender equality under religious law across a broad range of traditions. Much can be learned from comparing the struggles for ritual inclusion, interpretive authority, and equality under law in different religious traditions and different nations.

Some of the works in this series are directly comparative, such as Jan Feldmans study of religious womens advocacy in Israel and Kuwait in Citizenship, Faith, and Feminism and our anthology Gender, Religion, and Family Law. Others present an in-depth analysis of a single religious tradition. Jewish law is explored in Ronit Irshais Fertility and Jewish Law, Susan Weiss and Netty Gross-Horowitzs Marriage and Divorce in the Jewish State, and Margalit Shilos Girls of Liberty: The Struggle for Suffrage in Mandatory Palestine. Islam is the focus of Chitra Raghavan and James Levines book Self-Determination and Womens Rights in Muslim Societies, and Janet Bennions Polygamy in Primetime looks at the changing face of Mormonism in America.

Tichenors book on struggles over womens rights in Catholicism provides a detailed and incisive analysis of the decline and reemergence of the Catholic Church as a potent political force in postwar Germany. She demonstrates how the worldwide Catholic Church responded to womens demands by developing and emphasizing theological norms that made achievement of gender equality more difficult.

The Catholic Church has faced the dual challenge of declining interest among men in becoming celibate priests and of womens increasing demands to be allowed to take on a priestly role. Tichenor describes how the German Catholic Church resisted claims that it afford equality in achieving access to ritual roles and in shaping religious doctrine on contraception, abortion, and assisted reproduction. As in other religious traditions, Catholicism confronted the feminization of the community of congregants filling the pews and available to do the work of creating and maintaining communal religious life. As women took on much of the day-to-day work in churches (and synagogues), they began to ask why they should continue to be excluded from the more highly valued ritual roles of rabbi in the synagogue and altar server or deacon in the Catholic Church. Tichenor describes how this challenge was viewed by the Catholic Church as an attack not just on male dominance in the Church but also on the theological underpinnings of priestly power. Recognizing equality between men and women would necessitate recognizing equality between clergy and laity.

In other religious traditions, the creation of opportunities for advanced learning about religious doctrine has enabled women to become qualified to fulfill positions of religious leadership and to become informed challengers of doctrines that purport to exclude them on the basis of their sex. Over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, women have become eligible for ordination in other Christian denominations and in the more liberal branches of Judaism. In 2015 a small cohort of Orthodox Jewish women in America and Israel were ordained with authority to decide questions of law. Women have been recognized as pleaders in rabbinical and Islamic courts, as Islamic court judges, and as authorized interpreters of some branches of Jewish law, as yoatzot halacha.

Tichenors elegant and comprehensive work helps us understand how and why the Catholic Church has been able to resist similar demands and the implications its stance has had. She shows how even widespread demands for gender equality among members of a religious community may not translate into transformation of discriminatory religious norms. Many women and moderates have left the Church. The reconstituted body is even more conservative and punitive toward those seeking gender equality than the old Church.