The Eye of the Law

Two Essays on Legal History

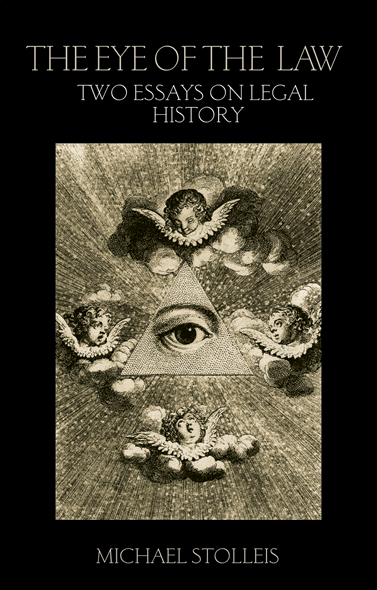

Written by the eminent German legal historian, Michael Stolleis, these two Essays on Legal History offer an original and compelling history of the symbolism through which law is characterised as being above us. In The Eye of the Law, the history of this metaphor is followed from antiquity through to the present day: from the Greek Eye of Justice, the eye of the impartial judge of the Underworld, the Eye of God watching past, present and future, the Eye of the Prince, guiding his subjects, to the almighty Eye of the Law. While our belief in the law may have become brittle, nothing escapes what is now the Eye of Big Brother. In the Name of the Law takes up the various formulas used to legitimate the decisions of the courts, from the times of absolutism, through the nineteenth century, until today. The speaker who speaks in the name of a higher being underlines his function: his authority comes from above. And it is in the name of god, king, people, state, nation, or law, that a weak, earthly, justice receives its support.

Michael Stolleis is Professor of Law and Legal History at the University of Frankfurt, and Director of the Max Planck Institute of European Legal History. He has been awarded the Leibniz Prize (1991), the Balzan Prize (2000) and honorary doctorates at the universities of Lund, Toulouse and Padua.

The Eye of the Law

Two Essays on Legal History

Michael Stolleis

Published 2009

by Birkbeck Law Press

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Birkbeck Law

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Birkbeck Law Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

2009 Michael Stolleis

Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Munchen 2004

This book is a translation of an original work Das Auge Des Gestezes by Michael Stolleis originally published in 2004 by Verlag C. H. Beck, Munchen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN13: 978-1-134-02810-8 ePub ISBN

ISBN13: 978-0-415-47273-9 (hbk)

ISBN10: 0-415-47273-3 (hbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-415-47274-6 (pbk)

ISBN10: 0-415-47274-1 (pbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-203-88981-7 (ebk)

ISBN10: 0-203-88981-9 (ebk)

Foreword

The blindness of law and the insight of justice

Costas Douzinas

Certain rare books carry a little bit of magic, they offer a kind of surplus value. They tell a story. How does (the metaphor of) the eye attach to law, for example? What kind of image comes to the fore when someone (a prince, a judge, a constitution) speaks in the name of the law? Their surface texture is full of historical detail, packed with artistic adornment, replete with sages and gods, brimming with princes and judges. Michael Stolleiss The Eye of the Law is such a book. It shows what it says, in semiotic terms it is deictic: if it talks about the eye of the law, it attracts the eye to look at laws eyes and pyramids, justices swords and scales. In this fantastical world of emblems and icons, the eye luxuriates on the Eye, vision reflects on visibility, on what it means for the eye to see itself, to contemplate its double.

Such are the seductions of the book you are holding. It bridges legal and art history, reminding us of the ars juris, the oldest juridical tradition. And yet while this book speaks about the visible and the nameable, while it gives the Eye to the eye, at the same time it makes us see differently: it is literally an allegory, an all agoreusis, another address or a speaking otherwise. You get the apparent story, the story of laws eye and name, well structured and presented with a beginning, a middle and an end, you get what you paid for. But like the magic of surplus value, you get more than you bargained for. The visible surface has its invisible side, an underlying plot; not some Greimasian deep grammar, but a labyrinthine story of the eye which calls the reader to see from another angle or place: an allegory about laws other scene, its heterotopia. In a few beautifully written pages, this book unravels before your eyes and discloses the story of law much more accurately and effectively than a sleepy librarys shelf-full of books by doctors and philosophers of law.

If the eye of the law majestically inspects the scene, pretending to be all-seeing, even when it is an evil eye, it is also a vulnerable eye, as Georges Bataille taught us. It mirrors in its reflection the story of laws coming to be and of its passing away, in the same way that the dead eye of the victim holds the image of his murderer. Books like Michael Stolleiss The Eye of the Law can teach you in their opulent images and parsimoniously wise text more than many a tome of the complacent exercises that largely pass these days as jurisprudence, the prudence of the law.

Why does the law have a head, eyes and mouth, a body with flesh? Why is law a person with a name, in whose name its servants and mouthpieces speak? How and when did the assumed qualities and characteristics of law become displaced, transferred to a person? Conversely, which assumptions about a person, about identity, integrity and unity, are displaced into justice, law, the state when they appear as single entities with the dignity of seeing, hearing, speaking a name? These are the questions that Michaels essays call us to see, to speculate on, naming at the same time the avenues of thinking we must transverse if we are to understand laws name. The remarks that follow attempt necessarily and impossibly to tease out some of the extra meaning, the excess value The Eye of the Law so generously offers to the unsuspecting reader.

Laws name

Semiotics explains how the subject of enunciation and the subject of statement are two separate speaking positions. In literature, for example, the subject of enunciation is the author of a novel, while the novels fictional narrator is the subject of the statement, (s)he who tells the story. This crucial distinction animates legal discourse and is most apparent in constitutional texts. The 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen speaks on behalf of humanity and its eternal and inalienable rights. The 1975 Greek constitution constitutes in the name of the most Holy Trinity. We the people of South Africa recognising the injustices of our past [and] honouring those who suffered adopt the new Republics 1995 constitution. In each case, the subject of enunciation is the constitutional assembly, but its statement is made in the name of God, humanity, the people. The constitutional legislator and the new sovereign are the result of revolution, war, violence. Yet this outcome of the history-changing and law-creating event claims to be a mouthpiece, the dummy of a higher ventriloquist authority.