Published by Messenger Publications, 2021

Copyright Thomas J Morrissey SJ, 2021

The right of Thomas J Morrissey SJ to be identified as the author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photography, filming, recording, video recording, photocopying or by any information storage and retrieval system or shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover image: Detail View of Drogheda , Gabriele Ricciardelli, fl. 17431782, 1754, Oil on canvas. Reproduced with kind permission Highlanes Municipal Art Gallery, Drogheda, Co Louth.

Maps on inside front and back covers from Atlas of Irish History , General Editor Sen Duffy, published in Ireland by Gill & MacMillan Ltd, 1997, and reproduced with kind permission.

ISBN 9781788123402

ePUB ISBN 9781788123433

Mobi ISBN 9781788123426

Messenger Publications,

37 Leeson Place, Dublin D02 E5V0, Ireland

www.messenger.ie

Acknowledgements

In researching and writing this book, I owe much to the knowledge and assistance of Damien Burke, of the Irish Jesuit Archives, and to the courtesy and support of the Librarian and staff of Milltown Park Library. Dr Fergus ODonoghue SJ was a most helpful and critical reader of the text, and he also made available to me his specialist knowledge of seventeenth-century Ireland. To Fr Paddy Carberry SJ this book owes much. His interest in the work, his advice and his painstaking editing of the text have made a considerable contribution to its eventual format. I am grateful to Sean Collins, MA, Drogheda, for his interest and background knowledge of the citys history; and to the Highland Municipal Gallery, Drogheda, for the splendid image of Drogheda in 1754. Once again, I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to the publisher and staff of Messenger Publications for their skill and consideration on all occasions. Finally, this book was made possible thanks to the interest and support of the Jesuit Provincial, Fr Leonard Moloney SJ, and to the support of the Rector and community of Milltown Park, Dublin.

Thomas J Morrissey SJ

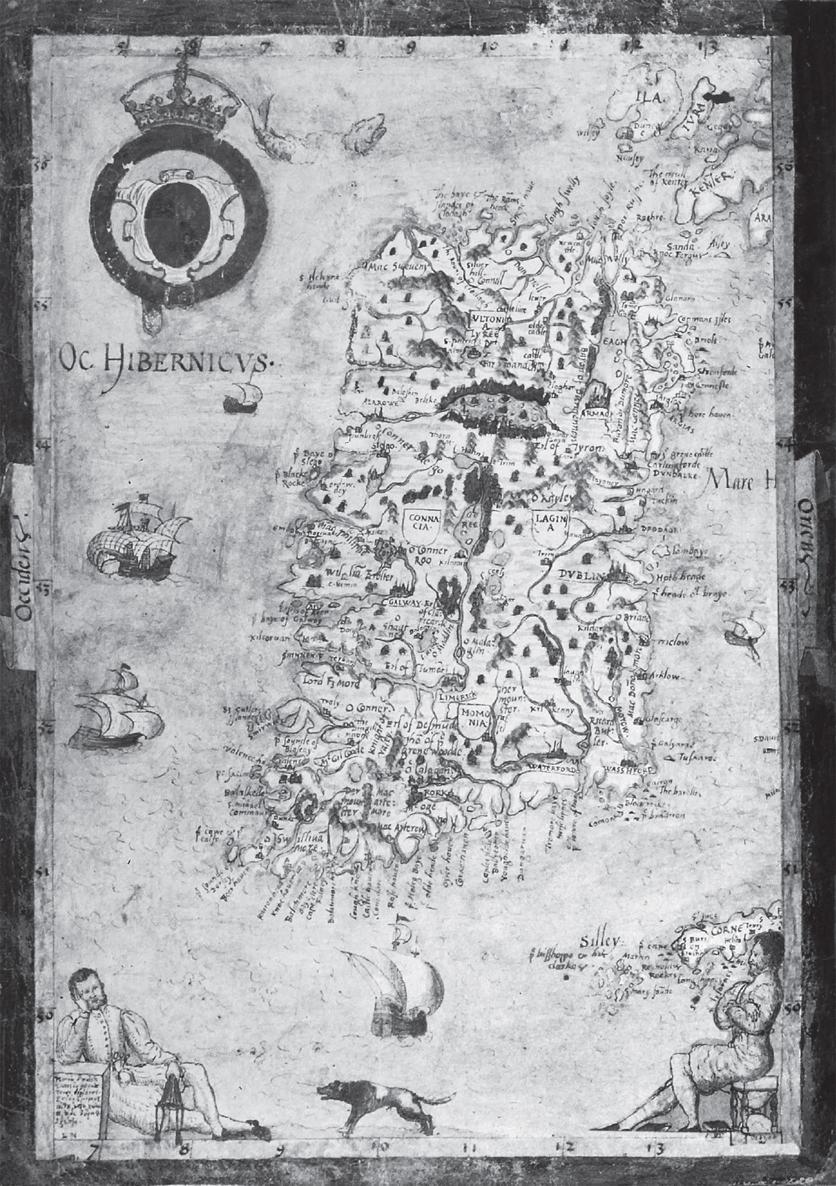

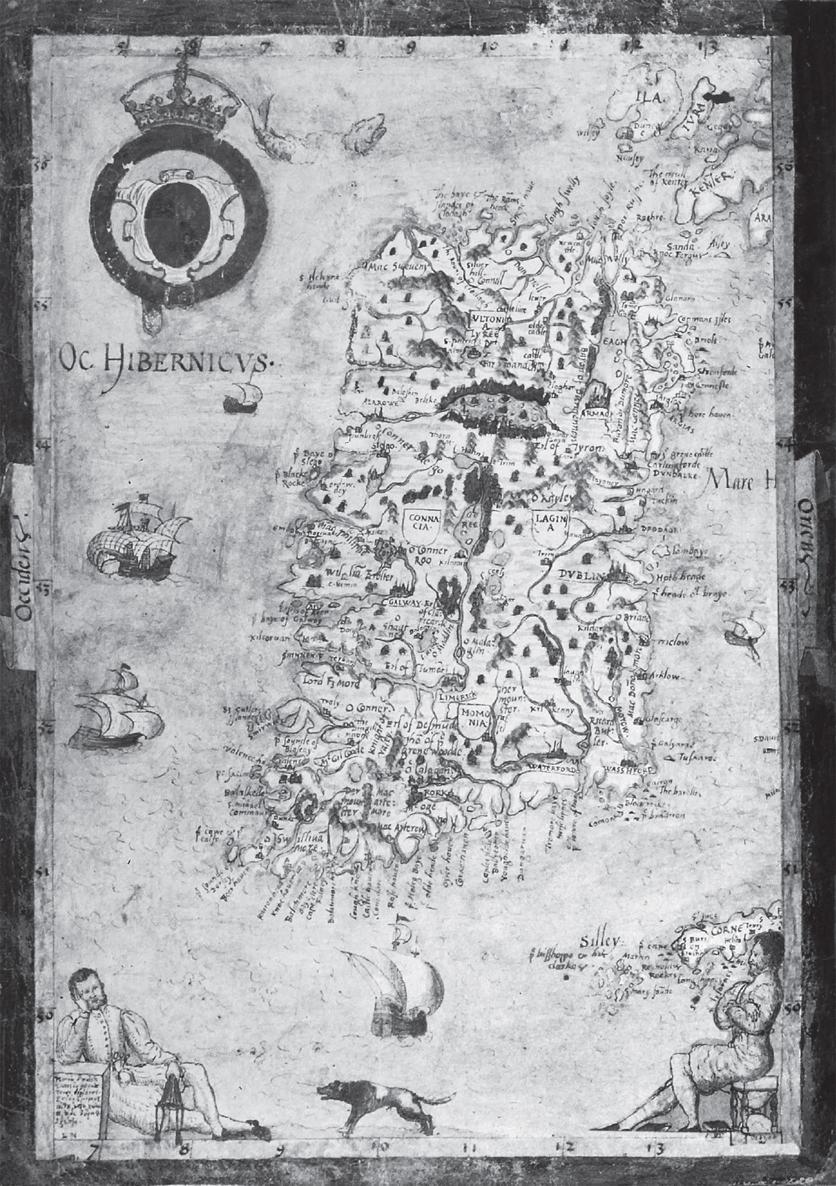

Map Image Marzolino / Shutterstock

Laurence Nowell, 1564

Foreword

IRISH Jesuits in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries lived in danger of imprisonment and death in their own country. They were fortified, however, by their membership of a wider body, the Society of Jesus, which was bringing new life to the Catholic Church. The Jesuits strength lay in the common spiritual and theological training of its members, and in their commitment to the God of mercy as revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. Jesuits were prepared, under obedience, to go to any place and to face any peril, including death, in the service of Christ. The special vow of obedience to the pope, which professed members made, added to the Jesuits status within the Church, while also making them a special target for enemies of the papacy.

During penal times, Irish Jesuits were trained abroad in Portugal, Spain, France, Italy and the Low Countries. From their experience in these lands, they were familiar with the impact their colleagues were making across most of Europe through their ministries in churches, schools, seminaries and universities and above all by the witness of their lives. The demand for Jesuit education in particular was immense. In 1593, Superior General Claudio Acquaviva (15811615) had to decline 150 invitations from all over Europe to open schools. At his death in 1615, the Society was conducting 320 colleges. In an era when spiritual reform was in the air, together with an eagerness for humanist learning, the Jesuit schools promoted this reform while providing a Christian humanist education. Their emphasis on the classical languages and on articulation in Latin, together with the attention given to drama, music and self-expression, contributed significantly to the European humanist tradition.

The Jesuit schools flourished in countries where the monarchs were supportive of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, such as Portugal, Spain, France and the Spanish Netherlands, but they also exercised considerable influence in Germany, Poland and central Europe.

The Jesuit schools that received most attention were usually those liberally sponsored by monarchs or princes, but the vast majority of them served a poorer population. By offering their services free of charge, these schools provided opportunities for numerous boys of ability to benefit from an education to which they otherwise could not have aspired. The Jesuit colleges proved an important agency for the renewal of Catholicism, and a significant number of future Jesuits came from them. A further important agency was the Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was far-reaching in its influence, and not only in the context of Jesuit schools. From cities throughout the world flowed a stream of reports about the effectiveness of this instrument for the formation of a spiritual elite in all classes of society.

The Jesuit influence stretched well beyond Europe, of course. From its earliest years the Society sought to bring the Gospel to India, Japan and even the closed empire of China. Subsequently, Jesuits were active among the indigenous populations of South and North America, and they frequently established schools in these territories. Among them was an Irish Jesuit, Thomas Field, from Limerick, who became celebrated as a missionary in Paraguay, where he died in 1626. By that date, the Society of Jesus had a membership of 13,000, and this continued to increase throughout the seventeenth century.

The present book is concerned with four Irish Jesuits who laboured in the seventeenth century, one of whom, James Archer, rose to prominence in the previous century. All four were involved in works that were characteristic of Jesuits across Europe. Three of the four devoted most of their attention to education.

For the benefit of the reader, the opening chapter, which is concerned with James Archer (15501620), begins with an account of the state of Ireland in the sixteenth century: its inhabitants, its structures of government and something of its history. That unhappy history caused Irish students to seek shelter in Spain from the end of the sixteenth century, opening the way for Irish Jesuits to become involved in their education. In time, the establishment and development of an Irish seminary college in Salamanca became the focus of the Irish Jesuits efforts. The purpose of the college was to teach and train young men who wished to be priests and who were prepared to return to Ireland to preserve the Catholic faith there.

James Archer was active in directing this college in its early years. To seek financial support for it, he returned to Ireland in 1596, but found on arrival that he was in danger of arrest. To evade the government agents, he sought shelter among the native Irish forces, led by Hugh ONeill, Earl of Tyrone. These forces were engaged in a struggle with the government in defence of their lands and their right to exercise their religion. Archer became active in support of their religious struggle, acted as emissary for ONeill to King Philip II of Spain, and travelled with the subsequent Spanish expedition to Ireland. Later, on his return to Spain, he was appointed procurator for all the Irish colleges operated by the Jesuits in Europe.