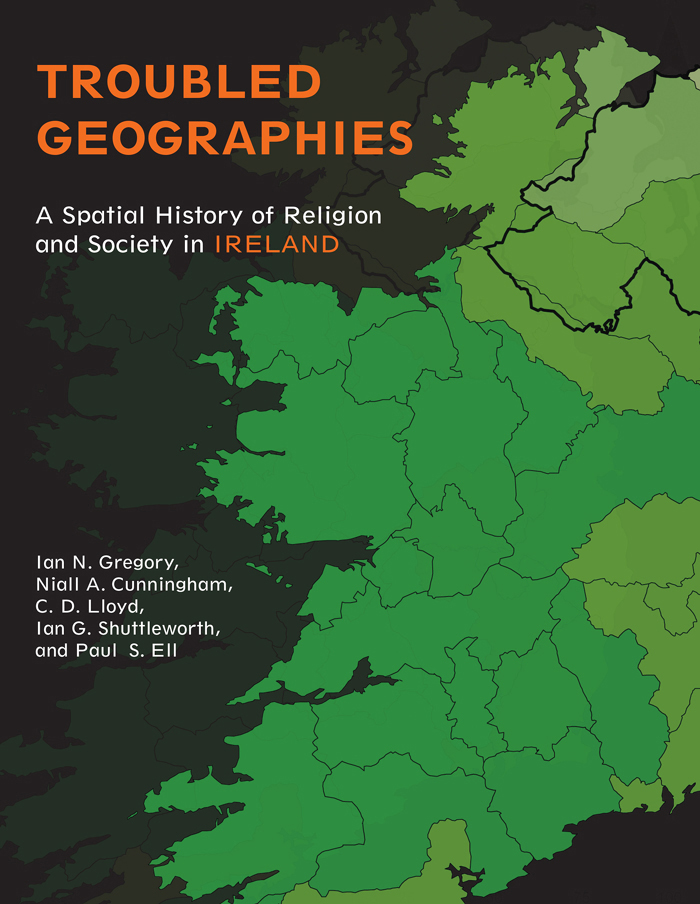

Troubled Geographies

THE SPATIAL HUMANITIES

David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, editors

TROUBLED

GEOGRAPHIES

A SPATIAL HISTORY OF RELIGION

AND SOCIETY IN IRELAND

IAN N. GREGORY, NIALL A. CUNNINGHAM, C. D. LLOYD, IAN G. SHUTTLEWORTH, AND PAUL S. ELL

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2013 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gregory, Ian N.

Troubled geographies : a spatial history of religion and society in Ireland / Ian N. Gregory, Niall A. Cunningham, Paul S. Ell, C. D. Lloyd, and Ian G. Shuttleworth.

pages cm. (The spatial humanities)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-00966-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-253-00973-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN (invalid) 978-0-253-00979-1 (ebook)

1. Human geographyIreland. 2. IrelandEthnic relations. 3. IrelandReligious life and customs. 4. IrelandSocial life and customs.

I. Title.

GF563.G74 2013

304.209415dc23

2013016440

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 13

The research that produced this book was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council/Economic and Social Research Councils Religion and Society Programme under grant AH/F008929/1 Troubled Geographies: Two Centuries of Religious Division in Ireland. It benefited from additional support from the British Academy under grant SG090803 The Presbyterian Church in Ireland, 18712001. Our sincere thanks go to Malcolm Sutton for allowing us to use his database of deaths during the Troubles and to Martin Melaugh (University of Ulster) for making the data set available to us. Many of the census data used have been taken from L. A. Clarkson, L. Kennedy, E. M. Crawford, and M. E. Dowling, Database of Irish Historical Statistics, 18611911 (computer file) (Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], November 1997, study number 3579); and from M. W. Dowling, L. A. Clarkson, L. Kennedy, and E. M. Crawford, Database of Irish Historical Statistics: Census Material, 19011971 (computer file) (Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], May 1998, study number 3542). Our thanks go also to Elaine Yeates and others at the Centre for Data Digitisation and Analysis, Queens University Belfast, for additional work on these and related data sets. Census data for the Republic of Ireland for 1981 to 2002 were provided by the Central Statistics Office, Ireland. Access to the grid square data for Northern Ireland were provided by the Census Office of the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Their use in this analysis benefited from Economic and Social Research Council grant RES-000-23-0478. Spatial data on Belfasts peace lines were downloaded from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Office website, http://www.nisra.gov.uk/geography/default.asp12.htm (23 September 2011). Many of the color schemes used benefited from input from ColorBrewer.org, http://www.colorbrewer.org (23 September 2011).

Troubled Geographies

Geography, Religion, and Society in Ireland: A Spatial History | |

Catholicism is seen as synonymous with Irish nationalism and republicanism, which have sought to remove British influence from Ireland.

Religion and territory thus are explicitly linked, a link that has at worst led to killing, arson, and other forms of violence aimed at establishing or protecting territorial control. While these are the most overt and unpleasant expressions of the impact of religious geography on Ireland, spatioreligious processesthe way in which religion and geography become intertwined with each other and a range of broader factors within societyhave a long tradition. Recent work by Alexandra Walsham has drawn attention to this link, seeing religious space in Ireland as a sort of theological palimpsest, constantly being written and overwritten by competing Catholic and Protestant imaginings of the past. opportunity and a range of other issues affecting almost every aspect of a persons life.

This intermingling of geography, religion, and the wider society is not new. Protestantism arrived in Ireland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the plantations, whose aim was to plant specific areas with English Protestants, loyal to the Crown, to defend English influence from the threats posed by indigenous Catholics. This took place against the backdrop of the wider European struggle between Protestant England and Catholic Spain and France. The plantations were focused on certain key strategic areas, including colonial Dublin and its historic sphere of influence known as the Pale, parts of Munster and the midlands, and west Ulster. Around the same time, Scottish Presbyterians arrived in large numbers in east Ulster, reflecting long-term economic and cultural links between southern Scotland and Ulster rather than the processes of large-scale, organized colonization.

The plantations laid the foundation for the fusing of religion, identity, politics, and geography, and, as will describe, many of the spatioreligious patterns that were laid down in this period have shaped, and been reshaped by, the processes that ran through nineteenth-and twentieth-century Ireland. These processes can be divided into two types. At one extreme there have been the short-term shocksperiods of intense violence or trauma that led to sudden upheavals. At the other there are the longer-term, more gradual processes associated with economic and social development.

The most obvious trauma was the period of violence from the Easter Rising in 1916 to Partition and the civil war in the early 1920s. The geographical legacy of this was the division of the island into the mainly Catholic Republic of Irelandor the Irish Free State, as it was first calledand the predominantly Protestant Northern Ireland. As In what is now the Republic, however, there have been fewer such problems, and the much smaller Protestant minority has generally coexisted in relative harmony with their Catholic neighbors.

These two periods of violence are not the only traumatic processes to have affected the geographies of Ireland over the past two centuries. The Great Famine of the late 1840s was the last major famine in western Europe, and its effects have been profound in both the short and long term. moves on to describe how the Famine caused the population to crash from over eight million to less than six million as a consequence of death and emigration. Stagnation followed such that the population recorded by the 1841 census is still the largest ever population of Ireland, a situation that is virtually unique in western countries, where populations have typically increased dramatically since the early nineteenth century. Geography, religion, and politics are also part of the story of the Famine. It was perceived to have disproportionately affected Catholic areas in the west of the island, and the British governments response, or lack of it, to the unfolding tragedy, combined with the indifference of absentee landlords, did much to stimulate movements for agrarian reform and Home Rule.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.