Armstrong - Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness

Here you can read online Armstrong - Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Armstrong: author's other books

Who wrote Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

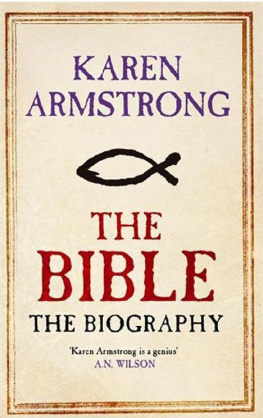

ALSO BY KAREN ARMSTRONG

Through the Narrow Gate

Beginning the World

The First Christian: St. Pauls Impact on Christianity

Tongues of Fire: An Anthology of Religious and Poetic Experience

The Gospel According to Woman:

Christianitys Creation of the Sex War in the West

Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on Todays World

The English Mystics of the Fourteenth Century

Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet

A History of God: The 4000-Year Quest of

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths

In the Beginning: A New Interpretation of Genesis

The Battle for God

Islam: A Short History

Buddha: A Penguin Life

Karen Armstrong

THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE

Karen Armstrong is the author of numerous other books on religious affairs, including A History of God, TheBattle for God, Through the Narrow Gate, Holy War, Islam, and Buddha. Her work has been translated into forty languages. She is also the author of three television documentaries and took part in Bill Moyerss television series Genesis. Since September 11, 2001, she has been a frequent contributor to conferences, panels, newspapers, periodicals, and throughout the media on both sides of the Atlantic on the subject of Islam. She lives in London.

1. Ash Wednesday

I was late. That in itself was a novelty. It was a dark, gusty evening in February 1969, only a few weeks after I had left the religious life, where we had practiced the most stringent punctuality. At the first sound of the convent bell announcing the next meal or a period of meditation in the chapel, we had to lay down our work immediately, stopping a conversation in the middle of a word or leaving the sentence we were writing half finished. The rule which governed our lives down to the smallest detail taught us that the bell should be regarded as the voice of God, calling each one of us to a fresh encounter, no matter how trivial or menial the task in hand. Each moment of our day was therefore a sacrament, because it was ordained by the religious order, which was in turn sanctioned by the church, the Body of Christ on earth. So for years it had become second nature for me to jump to attention whenever the bell tolled, because it really was tolling for me. If I obeyed the rule of punctuality, I kept telling myself, one day I would develop an interior attitude of waiting permanently on God, perpetually conscious of his loving presence. But that had never happened to me.

When I had received the papers from the Vatican which dispensed me from my vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, I was halfway through my undergraduate degree. I could, therefore, simply move into my college and carry on with my studies as though nothing had happened. The very next day, I was working on my weekly essay like any other Oxford student. I was studying English literature, and though I had been at university for nearly eighteen months, to be able to plunge heart and soul into a book was still an unbelievable luxury. Some of my superiors had regarded poetry and novels with suspicion, and saw literature as a form of self-indulgence, but now I could read anything I wanted; and during those first confusing weeks of my return to secular life, study was a source of delight and a real consolation for all that I had lost.

So that evening, when at 7:20 p.m. I heard the college bell summoning the students to dinner, I did not lay down my pen, close my books neatly, and walk obediently to the dining hall. My essay had to be finished in time for my tutorial the following morning, and I was working on a crucial paragraph. There seemed no point in breaking my train of thought. This bell was not the voice of God, but simply a convenience. It was not inviting me to a meeting with God. Indeed, God was no longer calling me to anything at allif he ever had. This time last year, even the smallest, most mundane job had had sacred significance. Now all that was over. Instead of each duty being a momentous occasion, nothing seemed to matter very much at all.

As I hurried across the college garden to the dining hall, I realized with a certain wry amusement that my little gesture of defiance had occurred on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. That morning, the nuns had knelt at the altar rail to receive their smudge of ash, as the priest muttered: Remember, man, that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return. This memento mori began a period of religious observance that was even more intense than usual. Right now, in the convent refectory, the nuns would be lining up to perform special public penances in reparation for their faults. The sense of effort and determination to achieve a greater level of perfection than ever before would be almost tangible, and this was the day on which I had deliberately opted to be late for dinner!

As I pushed back the heavy glass door, I was confronted with a very different scene from the one I had just been imagining. The noise alone was an assault, as the unrestrained, babbling roar of four hundred students slapped me in the face. To encourage constant prayer and recollection, our rule had stipulated that we refrain from speech all day; talking was permitted only for an hour after lunch and after dinner, when the community gathered for sewing and general recreation. We were trained to walk quietly, to open and close doors as silently as possible, to laugh in a restrained trill, and if speech was unavoidable in the course of our duties, to speak only a few words in a low voice. Lent was an especially silent time. But there was no Lenten atmosphere in college tonight. Students hailed one another noisily across the room, yelled greetings to friends, and argued vigorously, with wild, exaggerated gestures. Instead of the monochrome convent scene black-and-white habits, muffled, apologetic clinking of cutlery, and the calm, expressionless voice of the readerthere was a riot of color, bursts of exuberant laughter, and shouts of protest. But whether I liked it or not, this was my world now.

I am not quite sure of the reason for what happened next. It may have been that part of my mind was absent, still grappling with my essay, or that I was disoriented by the contrast between the convent scene I had been envisaging and the cheerful profanity of the spectacle in front of me. But instead of bowing briefly to the principal in mute apology for my lateness, as college etiquette demanded, I found to my horror that I had knelt down and kissed the floor.

This was the scene with which I opened Beginning the World, my first attempt to tell the story of my return to secular life. I realize that it presents me in a ridiculous and undignified light, but it still seems a good place to start, because it was a stark illustration of my plight. Outwardly I probably looked like any other student in the late 1960s, but I continued to behave like a nun. Unless I exerted constant vigilance, my mind, heart, and body betrayed me. Without giving it a seconds thought, I had instinctively knelt in the customary attitude of contrition and abasement. We always kissed the floor when we entered a room late and disturbed a community duty. This had seemed strange at first, but after a few weeks it had become second nature. Yet a quick glance at the girls seated at the tables next to the door, who were staring at me incredulously, reminded me that what was normal behavior in the convent was little short of deranged out here. As I rose to my feet, cold with embarrassment, I realized that my reactions were entirely different from those of most of my contemporaries in this strange new world. Perhaps they always would be.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness»

Look at similar books to Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Spiral Staircase: My Climb Out of Darkness and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.