First Published 1985 in Great Britain by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and in the United Stales of America by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

270 Madison Ave,

New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

Copyright 1985 Elmar Dinter

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Dinter, Elmar

Hero or coward.

1. WarPsychological aspects

I. Title II. Held oder Feigling. English

355 02019U22.3

ISBN 0-7146-3230-9 (hbk)

ISBN 0-7146-4048-4 (pbk)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Frank Cass and Company Limited.

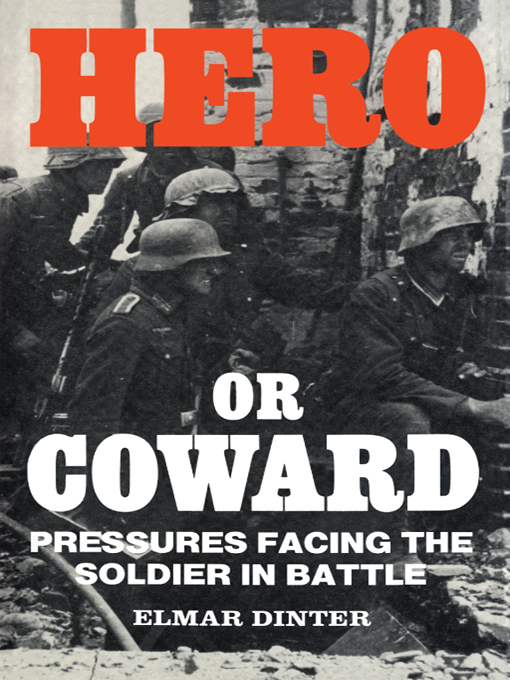

Cover illustration: The Battle for Stalingrad. German infantry group sheltering behind a wall in the mined city of Stalingrad. By permission of the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Contents

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

Acknowledgements

I received a great deal of help in the preparation of this book and I should like to mention especially:

The Staff College, Camberley, which under the command of Major General D.B. Alexander-Sinclair and his deputy Brigadier J.B. Bettridge constantly provided me with fresh inspiration.

Its Librarian, Mike Sims who helped me considerably with the translation and editing of the English version.

His predecessor Ken White who with his staff helped me to obtain source material.

My wife Ulrike, and Tricia Hughes who prepared the German and English manuscripts respectively.

Enid Martin and Sheena Lill of the Staff College Work Production Centre, who prepared the illustrations.

The Directing Staff and students of the Staff College who assisted me with their helpful discussions.

And, last but not least, my sons Christian and Tim who suffered with equanimity the fact that their father, for many months, spent his spare time reading and writing and not with them.

I am indebted to them all and it is to them that this book is dedicated.

Elmar Dinter

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

For every soldier without battle experience, the question of how he would react to the physical and psychological pressures of war is both fascinating and frightening. The thoughts and emotions which this question evokes are similar to those of mountain climbers on a rock face, or of ocean sailors who have got themselves involved in an adventure which, in spite of the excitement, has dangerous aspects.

Even though the average soldier will not seek battles, and even if war, with its terrors for combatants and non-combatants alike, can hardly be described as an adventure, the individual in the fighting is faced with the same challenge as men engaged in an adventure: that of proving himself. He may well ask: Will I emerge from the battle as a hero or as a coward?

Even when talking to soldiers with battle experience it becomes evident that they too ask themselves the same question over and over again. Although they are aware that their successful performance can be counted as a positive experience, they are aware too that they must always prove themselves anew and that every battle will involve new terrors.

Even for those who have never served in the armed forces and do not intend to do so, this question is both fascinating and disturbing, because the answer to it aims very quickly at the deep conscious and unconscious inner self, past the somewhat shallow terms of hero and coward. In this investigation of the inner self, one almost feels like a potholer, who would love to know where the labyrinth of passages and caves will lead him and what it contains, but knows that each step takes him ever further from the apparent safety of the surface.

The answer to the question is not only intriguing and exciting for the individual, but is the decisive criterion for the selection of personnel, the organization, equipment, training, education, leadership and tactics of armed forces.

If, for example, the dominating role of the small group is demonstrated, the organization must take it into account. If noise is an above average pressure, this could be allowed for in the development of weapons and equipment. If lack of understanding in certain fields results in additional nervous strain, the subjects studied and the time allocated for training should be altered. If formal discipline provides definite moral support in battle, it should be part of a soldiers training; and if the pressures the leader faces are different from those of his men, this will affect personnel selection. This should suffice as an indication the subject is dealt with at length later in the book.

Because of the importance of this topic to the military leader, this book is directed at him rather than at the scientist, and discussions of a technical nature such as the distinction between fear and anxieties are avoided as far as possible.

There will be many answers to our question. Nothing is gained by listing them all; this would only highlight conflicting requirements some of which could not be realized. Some would be contradictory. Others might be too expensive or run counter to the ethics of society.

Therefore, it is essential that the different pressures and their consequences should not only be enumerated, but should be compared, weighed and placed in an order of priority. This is the main aim of this study.

Let us consider, for example, possible consequences for the organization of the armed forces. If group cohesion proves to be important, this might require the setting up and maintenance of stable groups. However, there are also justifiable demands for movement of personnel, and this becomes particularly important in battle. It is equally vital for leaders, who can broaden their experience only in this way. Movement also makes it possible for ambitious soldiers to get promotion, and it ensures adequate replacements. It may also assist in the admission of women in order to achieve equality. All these points of view must be taken into account. Mere listing would be of little value. Only comparative assessment will get us any further.

Thus it is not merely a case of investigating what weighs on the soldier in time of war; what matters is to find out the decisive pressures and then to set out the conclusions in some order.

Finally, it is helpful to disclose to the soldiers themselves the answers to this question. With a full knowledge of what they can expect in war, soldiers without battle experience are in a better position to control their own reactions. By taking appropriate measures, commanders are able to reduce the effects of the pressures. Here, too, knowledge is helpful. It prepares the individual and the group for battle conditions. The terrors are depressing enough. Almost everyone will try to avoid them, but if this is not possible, they are more bearable this way.