ALSO BY PETER BEBERGAL

The Faith Between Us (coauthored with Scott Korb)

Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood

JEREMY P. TARCHER/PENGUIN

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright 2014 by Peter Bebergal

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Most Tarcher/Penguin books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write: Special.Markets@us.penguingroup.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bebergal, Peter.

Season of the witch : how the occult saved rock and roll / by Peter Bebergal.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-698-14372-2

1. Rock musicHistory and criticism. 2. Music and occultism. 3. Mysticism in music. 4. MusicPhilosophy and aesthetics. I. Title.

ML3534.B38 2014 2014027012

781.66dc23

Version_1

For my father, my captain, my friend, Byron Leon Bebergal (19282014)

CONTENTS

My hair is holy. I grow it long for the God.

EURIPIDES , The Bacchae

INTRODUCTION

WE ARE ALL INITIATES NOW

I

In 1978 my older brother had just joined the air force, leaving me access to the mysteries of his room. The suburbs of southern Florida were row after row of single-level ranch houses and manicured lawns. I was eleven, filled with restless, inexplicable feelings. It was just before the dawn of puberty. Except for what I could glean from my brothers dirty magazines, sex was still an abstraction. Some other secret thing was beckoning. I had caught glimpses when I heard the music coming from his room, so different from my own small collection of Bay City Rollers and Bee Gees 45s. One by one, I began to play his records, holding the sleeves in my lap, trying to learn the grammar of this new musical language. I was not quite prepared for what I found. His music made me feel hot and cold at the same time, a small fire starting in my belly while shivers ran up my spine. Here was a seductive and impenetrable catalogue of arcane and occult symbols, of magic and mystical pursuits, of strange rituals involving sex, spaceships, and faeries. I went into his room looking to hear some real rock and roll. I came out spellbound and hypnotized by the spectacle.

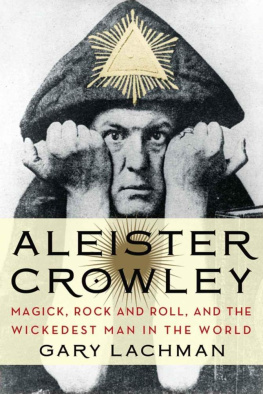

The record collection was a lexicon of the gods: the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Arthur Brown, King Crimson, Hawkwind, Yes, Black Sabbath, and Pink Floyd. Already immersed in the arcana of the 1970s by way of J. R. R. Tolkien reprints, Dungeons & Dragonsalmost universally known as D&DHeavy Metal magazine, horror comics, and the animated films of Ralph Bakshi, I sat in long hours of deep listening, studying the lyrics, the album cover art, and even the hidden messages etched into the inner ring of the vinyl. I searched for the clues to Paul McCartneys rumored death and felt the chill of ghosts staring out from the cover of Abbey Road, the barefoot Beatle unwittingly symbolizing his own demise through some terrible necromancy. I held the vinyl of Led Zeppelin III up to the light so I could search for the fabled occult missive carved into the records inner ring: Do what thou wilt. I stared in nervous fascination at the various characters inhabited by David Bowie and tried to crack the mystery of his lyrics that told of aliens, Aleister Crowley, and supergods who are guardians of a loveless isle. Black Sabbath was formed by sorcerers, working their dark art through heavy doom-laden riffs. Arthur Brown admitted he was the god of hellfire.

The music became a fixture of my psyche. I thought I alone had uncovered a well of arcane truth, like the paperback Necronomicon that sat on my bookshelf. There was something both transcendent and abysmal lurking within the grooves of these records and the fantastic lives of the characters inhabiting them. Roger Deans artwork on Yes albums were landscapes once populated by ancient races, their arcane wisdom lost, sunken like Atlantis. At the other end of the spectrum was the Beatles impenetrable and terrifying penultimate song on the White Album, Revolution 9, a spoken-word, feedback-infused collage of hidden occult messages suggesting a palpable violence. These often opposing qualities nonetheless shared a common thread: they referenced a reality beyond normal perception, a vast metaverse inhabited by demons and angels, aliens and ancient sorcerers, all of which could be accessed by potentially dangerous methods such as magic, drugs, and maybe even sex. But I also sensed the peril in reading too deeply into these songs and albums. The film Helter Skelter, often shown on the UHF channels late-night movie programs, taught me that fixating on a bands life and work can sometimes take a fanatical turn. In this instance, an album helped to precipitate a murderous call to arms when Charles Manson believed the Beatles were sending him secret, violent messages through their music. Although the connection between the music and the murders was overblown, my adolescent self couldnt shake the feeling there was something to the Beatles songs that made this kind of interpretation possible. And sure, it was crazy to think so and everyone knew it wasnt true, but maybe, just maybe... Paul really was dead.

Despite my ambivalence about my teenage fantasies, my brothers albums really were a glimpse into the sometimes explicit, sometimes hidden occult language of rock, a window into the pervasive influence of magic and mysticism on the most essential and influential art form of the twentieth century. Within a single collection representing a microcosm of rock history and styles was another hidden story, of how rockits songs and its staging, its lyrics and its pyrotechnicshave been shaped by magical and mystical symbols, ideas, and practices.

Like many teenagers in those days, I wondered if magic really did exist outside the lists of spells in the D&D Players Handbook. I bought books on white magic and lit candles, making sure the window was open so as to not alert my mother, who was ever on the lookout for the danger of an open flame. My friends and I dimmed the lights and hovered our fingers over the plastic planchette of my Ouija board. Nothing seemed to manifest. I could not pull out of thin air the potent feelings that came from those records. There was magic here, but it was even bigger than I could have imagined. From between the gatefold covers, from the vinyl tucked snugly into the sleeves, an enchantment had been woven that bewitched all of popular culture.