JAA (Jaa Mrevlje-Pollak) is one of the most prolific and influential contemporary European visual artists of his generation. He trained at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, where he graduated in 2004 with distinction and where he continues to teach. He has been featured in numerous publications, including Modern Painters, the Art Newspaper, and Art in America. Based in Ljubljana and New York, he has exhibited his work around the world, including at Frieze London and New York and at the Venice Biennale. Learn more at www.jasha.org.

* * *

Dr. Noah Charney is the internationally best-selling author of more than a dozen books, translated into fourteen languages, including The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art, which was nominated for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Biography, and Museum of Lost Art, which was the finalist for the 2018 Digital Book World Award. He is a professor of art history specializing in art crime and has taught at Yale University, Brown University, American University of Rome, and University of Ljubljana. He writes regularly for dozens of major magazines and newspapers, including the Guardian, the Washington Post, the Observer, and the Art Newspaper. Learn more at www.noahcharney.com.

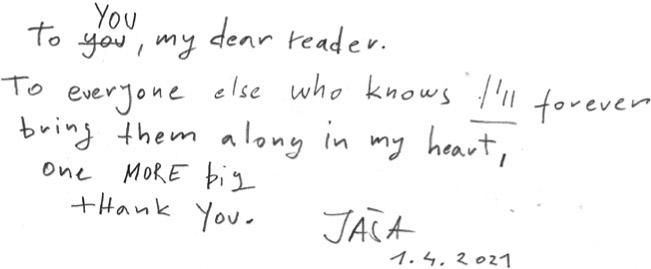

I f there is anything I got wrong and if anything offended you in some way, none of it was done intentionally. We have changed a detail or two on purpose, just to avoid unnecessary misunderstandings. All the rest is true to fact, at least as I have seen and lived it. I wrote this book thinking of everyone who made me, everyone I had the privilege to meet and share precious moments with on this incredible journey. My love goes to all of you, even if you do not see your name inscribed here.

The format and purpose of the book did not allow me to include you all, as we had to cut out whole passages in the editing process, all in our pursuit of universalityof my story talking to as many as possible out there, those who do not know me yet.

1

ON ORIGINS AND EARLY YEARS

I saw the Sistine Chapel as a lively and restless five-year-old. I was a major pain in the ass for my parents. At one point, they stopped taking me to restaurants, as I kept trying to sneak over and grab one corner of the tablecloth, my eye level at the time barely higher than the cutlery as it lay there. Then I would pull the tablecloth, filled plates and brimming glasses and flatware and all, onto the floor. There I would stand, the contents of the table piled at my feet, shattered glasses and chipped plates and lots of food, the tablecloth now hanging from my enthusiastic hands. I did this a lot, until my parents realized that it was best if I stayed home when they went out to eat.

The trip to Italy was a gift for me, though my two sisters were grumpy about having been left behind for the first time. My mother, father, and I were off to Rome for the wedding of the black sheep in the family, my lovably deviant uncle. Walking into the Sistine Chapel was the zenith of a trip that made me who I am more than I ever could have realized at the time. It is what led me to live in Italy, to study in Venice, once the idea of becoming an artist had infected me to such an extent that I knew there was simply no other way for me to live.

I remember holding my mothers hand that day. I remember the crowd, the voices, the immensity of the chapel. What I remember most was the gloom of the veil of human flesh, the browns it was before the chapel was famously restored to its current (and original) Day-Glo proto-Mannerist brightness. Back then it appeared stained, as if coffee had been spilled down the walls. At that point, the prevailing brown associated with human bodies left an indelible mark on me.

It was the climax of the trip thanks to my mother, who had hyped it up in anticipation of the visit. She talked about this Michelangelo guy, an artist who had worked for years on it, high up against the ceiling, rarely washing, eating, or sleeping, but managing to achieve, in the end and against the odds, this incredible thing, the Sistine Chapel. Holding my hand inside the colossal space, she leaned down toward me and pointed out Michelangelos self-portrait, hidden among his army of saints and devils, saying, You see, Jaa, this is him. He painted himself as the loose skin that Saint Bartholomew is holding. That is his self-portrait. Thats Michelangelo.

The only thing I remember afterward is absolute and utter terror and panic. It all started shaking, and I started screaming like mad. My father came running, and they took me out of the Vatican immediately.

On the way back home to Yugoslavia from the wedding, we stopped in Genoa. My mother took me into a church. Seeing the inside caused an even worse reaction in me, and my mother had to promise that I would never again have to go into any church. And so it was, for years.

I only recently managed to overcome this fear, as entering a church always causes an overwhelming emotional, and in many cases physical, reaction. I experienced a similar sensation as a twelve-year-old when I walked into a modern art museum in Vienna. It provoked a similar fear that I knew well from those past panic attacks in churches.

DO I NEED TO HAVE SOME ORIGIN STORY TO BE AN ARTIST, AS IT SEEMS THAT MOST ARTISTS HAVE THEM?

As artists, we tend to mythologize our youth all the time. Am I an artist because I was born one? Was there some lunar movement that set me on my path? Was it because my parents blasted Mozart or Pink Floyd into my crib? Or was it the laughter and all the fights I overheard while unconsciously cocooning in my moms belly that made me who I am today? Does our origin really have anything to do with it?

So many stories of great artists, dating back to Giorgio Vasaris 1550 Lives of the Artists the first great biography of artists that helped establish how we in the modern world think of art, its history, and the people who create itbegin with some origin story of miraculous talent or deed in extreme youth. Sigmund Freud published a whole book analyzing Leonardo da Vinci and beginning with Leonardos earliest recollection of being attacked by a vulture while still in his crib. Vasaris biography of each artist begins with some early trauma or demonstration of artistic talent, so maybe its his fault that we all look for such origin stories to explain why we want to become that strangest of professions, an artist.

Perhaps it was thanks to my father, a renowned psychiatrist, who took me to lunch during a visit home after having left to study art at the Accademia in Venice, saying, You always were extremely problematic. Apart from being hyperactive, your behavior was, from an early age, borderline. It was clear to me that, if we did not take the right measures, you would end up as a criminal. Probably a very successful one, but a criminal. As that did not happen, I knew that a different option had opened for you. You had to channel your boiling energy. I knew that, if you could maintain your course, you could do something great.

I know exactly what you might be thinking at this point. Another case of a parental experiment. I was a wild child, hyperactive (as he would put it) and adorable but often a handful without a pause button (as my dear mother would put it). I knew exactly what he was talking about, so not only did it not come as a shock, it came at the right moment. I just did not yet know how to fulfill his prescient comment, but I felt that hed helped reveal one of my hidden secrets. It was liberating, like I could jump out of my skin, scream my lungs out, make love to everyone, ride on a cloud, while tiptoeing along the edge of an abyss, that ecstatic, intoxicating notion of beauty.