Navajo Code Talkers

Navajo

Code

Talkers

Nathan Aaseng

Copyright 1992 by Nathan Aaseng

All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce, or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018.

First published in the United States of America in 1992

by Bloomsbury Childrens Books

This electronic edition published in 2002

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aaseng, Nathan.

Navajo code talkers / Nathan Aaseng.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Describes how the American military in World War II used a group of Navajo Indians to create an indecipherable code based on their native language.

eISBN 978-0-802-72142-6

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

MOST VICTORIOUS SOLDIERS the world over return home to parades, medals, and statues built in their honor. Not true for those who served as Navajo code talkers during World War II whose battlefield contributions to victory were classified and kept secret for many years.

Navajo marine veterans were ordered not to reveal their mission as Navajo code talkers or, more precisely, as top-secret communicators. The designation "Navajo code talker" had not been coined yet and was utilized on a very limited scope. The code name for Navajo marine communicators was "talker" or "Arizona" and, occasionally, "New Mexico." The name Indian or Navajo was never used.

Nathan Aaseng's saga of unforgettable valor is a gripping chronicle of young Navajo men whose homeland was decimated and whose ancestors had been taken captive less than one hundred years prior to their becoming United States Marines. In spite of nearly two hundred broken treaties and the attempted eradication of their language by the Federal Indian Education System, they responded to the call to arms by the United States of America. Leaving behind the taste of lye soap with which teachers washed out their mouths for speaking their native language, they went on to develop the only unbreakable code in military history. They not only developed the code, but risked their lives to use it in hundreds of battles in the Pacific theater.

During World War II, Japan's code breakers were among the finest in the world. There was not a single message these experts could not decipher. But when the Navajo code talkers arrived in the Pacific, the Japanese code breakers met their match. It has been said that the Navajo Code Project was guarded as closely as the famed Manhattan Project, which was responsible for the development of the atomic bomb.

Marine code talkers were usually in the first wave of every island assault so that command centers could be immediately established and orders and directions could be secretly communicated to troop leaders. Although they were not a separate fighting unit, two and sometimes three code talkers were assigned to units of all six marine divisions. My own baptism by fire was on Okinawa where I went ashore with the first assault wave of the Seventh Regiment, Second Battalion, First Division.

At times, both my partner and I would be assigned to duties other than communications. As we manned thirty-caliber machine guns during Japanese assaults, we were always on the alert for the call "talker" from communications, which indicated an incoming Navajo code message or the urgency for a transmission. During an assault on Dakesha Ridge, my unit was pinned down for two days under heavy enemy fire, during which time the antenna on my radio was shot off. Using a pair of field wire cutters I succeeded in reconnecting the damaged antenna and reestablishing the transmission of messages in Navajo code calling for artillery fire and air strikes.

Many of the officers under whose leadership we served have stated the value of an unbreakable code in many of the Pacific battles. One major summed it up when he said, "without the Navajo code, we would never have taken Iwo Jima."

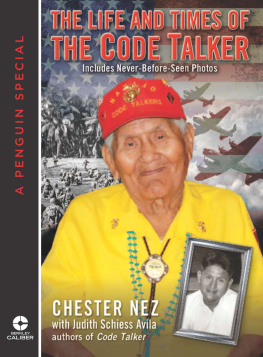

Nathan Aaseng's Navajo Code Talkers is a compelling and realistic portrait of all the courageous Navajo marines and the long-lasting contribution to freedom made by this dedicated group. I am pleased to have served these men as both the former president and current vice president of the Navajo Code Talkers Association. The association was founded in 1972 to foster, encourage, and perpetuate the experiences and friendships of our service; to exhibit patriotism and love of country; and to aid in the education of our descendants.

After fifty-eight years the United States Congress has enacted legislation awarding the Congressional Gold Medal and the Congressional Silver Medal to this unique group of United States Marines. Although we had to work in secrecy, we are delighted that readers will finally know our story.

Roy O. Hawthorne

Vice President of the

Navajo Code Talkers Association

US. MARINES ADVANCING ACROSS the Pacific island of Saipan during World War II hacked their way through lush, tangled wilderness and dense sugar-cane plantations. Steep ravines and rugged volcanic mountains barred their path.

There was no such thing as a battle line for these soldiers. Danger lay not just ahead of them, but also to the side and possibly even behind. The unseen guns of the enemy were hidden by the pitch dark of night, by the thick tropical vegetation, or by the walls of caves that burrowed deep into the mountains.

Each soldier knew his next step might be his last. The rustling of leaves a few yards away in any direction was as likely to be an enemy as a friend.

On the extreme left flank of the American forces trying to capture Saipan, a battalion of marines ran into blistering volleys of fire from determined Japanese defenders. In the furious struggle that followed, neither side gained any ground. One morning, however, the marines noticed a strange silence along the enemy front. Cautiously scouting the terrain, they discovered that the Japanese had abandoned the area and retreated to new defensive positions. The marines crept forward.

Suddenly, artillery shells exploded all around them. Hugging the ground to protect themselves from flying shrapnel, the marines soon discovered that the bombardment was coming from far behind them, obviously from their own artillery units!

Those American gunners were following orders to blast away at the Japanese in those positions. They had no way of knowing that the Japanese had pulled out and that U.S. Marines now occupied the area. Quickly, one of the marines radioed to headquarters, frantically calling for a stop to the bombardment.

Now the artillery commanders faced a knotty problem. The Japanese were in general far more fluent in English than the Americans were in Japanese. They often pretended to be Americans and sent out false radio messages in English. If the receiver believed these message, traps could be baited and entire battle plans disrupted. Was this one of those fake messages, sent out to halt a much needed artillery attack? Unfortunately, in the confusion of the scattered battle lines, there was no quick way of finding out just what was true.

Next page