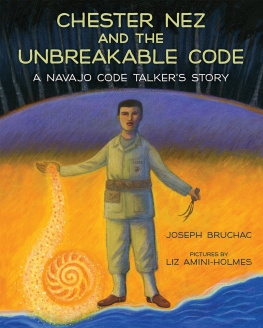

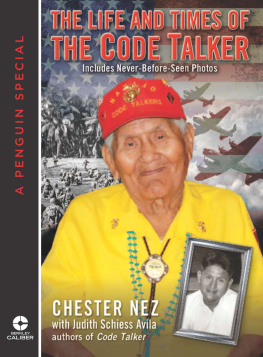

THE NAVAJO CODE TALKERS

OF WORLD WAR II

Cloaked in secrecy and syntax, code machines were the pride of World War II cryptographers. State-of-the-art devices with cryptic names like Enigma, Purple, and The Bomb, these black boxes used rotors and ratchets to shroud messages in a thick alphabet soup. But U.S. Marines storming Pacific beaches used a different kind of code machine. Instead of rotors, each Marine cryptograph had two arms, two legs, an M-1 rifle, and a helmet. Their code name was Dineh The People. In English, they were called Navajos.

As Marines fought cave to cave on Iwo Jima, a foreign language crackled over field radios. Bombers were called jaysho (buzzards), and bombs were ayeshi (eggs). The commanding officer was bihkehhe (war chief), and each platoon was a hasclishnih (mud clan). On the morning of February 23, 1945, when six soldiers on a mountaintop hoisted the Stars and Stripes for all the world to see, the word went out in code: Naastsosi Thanzie Dibeh Shida Dahnestsa Tkin Shush Wollachee Moasi Lin Achi. Marine cryptographers translated the Navajo words for Mouse Turkey Sheep Uncle Ram Ice Bear Ant Cat Horse Intestines, then told their fellow Marines in English: The American flag was flying over Mount Suribachi.

In most movies, the Navajos speak in a primitive pidgin and still fight on horseback. But long after the West was won and lost, a group of Navajo patriots sharpened speech into a precise weapon and went to war for the nation that surrounded their own. They hit every Pacific beach from Guadalcanal to Okinawa, but their story is at best a footnote in war chronicles. They are the Navajo Code Talkers, and theirs is one of the few unbroken codes in military history.

More than 3,600 Navajos served in World War II, but only 420 were Code Talkers. Members of all six Marine Corps divisions in the Asian-Pacific Theater, they coded and decoded messages faster than any black box, baffling the Japanese with a hodgepodge of everyday Navajo and some 400 code words of their own devising. In early Pacific invasions their code was barely used by skeptical officers, but Marine commanders came to see it as indispensable for the rapid transmission of classified dispatches. For three critical years, these Navajo linguists proved that when it came to heroism, The People, too often known for their silence, spoke volumes.

Like all Americans of his generation, Keith Little remembered exactly where he was when he heard the news of Pearl Harbor. Little recalled the boarding school on the reservation of Ganado, Arizona. He and his fellow students had some choice words for the cafeteria gruel, Little remembered. So on Sunday afternoon, December 7, Me and a bunch of guys were out hunting rabbits with a .22. We had a rabbit cooking down in the wash, and somebody went to the dorm, came back and said, Hey, Pearl Harbor was bombed! One of us asked, Wheres Pearl Harbor?

In Hawaii.

Who did it?

Japan.

Whyd they do it?

They hate Americans. They want to kill all Americans.

Us, too?

Yeah, us too.

Then and there, we all made a promise, Little recalled. We were, most of us, 15 or 16, I guess. We promised each other wed go after the Japanese instead of hunting rabbits.

The morning after Pearl Harbor, the superintendent of the Navajo reservation looked out his office window. There stood dozens of ponytailed men in red bandanas, carrying hunting rifles, ready to fight. A year earlier the Navajo Tribal Council, acknowledging a world at war, had unanimously resolved to defend the United States against invasion. There exists no purer concentration of Americanism than among the First Americans, the council declared. But on December 8, 1941, the Navajo volunteers were sent home. No official call to arms had been issued, and besides, most of the men only spoke Navajo.

When the war broke out, Philip Johnston was working in Los Angeles as a civil engineer. With wire-rimmed glasses and a buttoned-down mind, Johnston did not seem a likely candidate to speak Navajo. Yet as the son of missionaries, he had grown up on the Navajo reservation in Arizona. Decades later, reading about an Army test of Native American languages in combat maneuvers, Johnston had a mousetrap of an idea. During World War I, Indians in the American and Canadian armies had sent messages in their native languages. But lacking words like machine gun and grenade, their use was limited. Early in 1942, Johnston visited the Marine Corps Camp Elliott, north of San Diego to propose an up-to-date code he guaranteed would be unbreakable. The Marines were skeptical at first, but a few weeks later Johnston returned with some Navajo friends. For 15 minutes, while the iron jaws of Marine brass went slack, the Navajo translated messages from English to Navajo and back. Code machines would have taken up to 30 minutes to make the translation; the Navajo did the same work in seconds. A few days later, Marine Commandant Thomas Holcomb received a letter describing the test and urging the recruitment of Navajo men whose language is equivalent to a secret code to the enemy, and admirably suited for rapid, secure communication. In April 1942, as the Japanese sent American prisoners on the Bataan Death March, Marine recruiters set out for the land of Changing Woman, the Navajo fertility goddess.

The Marines had been from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli, but they had never seen a place like the Navajo Nation. Scattered across the red-rock Southwest desert, fewer than 40,000 Navajos lived in a territory the size of West Virginia. The reservation had few paved roads, no electricity or plumbing, only a handful of schools. Nearly all Navajos herded sheep, lived in houses called hogans and bought what little they could not grow or make at the nearest trading post. Recruiters set up tables in the sagebrush and sandstone, called them enlistment offices and began looking for a few good men fluent in Navajo and English. Recruitment figured to be a tough job.

Fewer than 80 years had passed since the Navajo Nation had fought against the U.S. military. In 1864, following Kit Carsons scorched-earth campaign, bands of starving, ragged Navajos were forcibly marched 350 miles across New Mexico. Along the way, some 200 died, while others staggered on, bewildered, heartbroken at the loss of their land. Navajos called the brutal relocation The Long Walk, and although the evacuees were returned to their land after four years, by 1942 the horror was still fresh in tribal memory. Meanwhile, battles with the federal government continued. Even as Navajo were volunteering to fight in the war, President Franklin Roosevelts administration was destroying their sheep to reduce soil erosion and overgrazing. Why would men fight for a nation that had humbled their ancestors, killed their herds, and would not let them vote? (Voting rights for Navajos were restricted until 1948 in Arizona, 1953 in New Mexico, and 1957 in Utah.) Why do you have to go? asked one mother. Its not your war. Its the white mans war.

From nation to nation, soldiers enlist for reasons that lose nothing in translation, including jobs, adventure, and patriotism. The Navajo had a different reason a global one. What happened to the Navajos in the past were social conflicts, said Albert Smith, a soft-spoken, highly spiritual man and former president of the Navajo Code Talkers Association in Gallup, New Mexico. But this conflict involved Mother Earth being dominated by foreign countries. It was our responsibility to defend her.

The Navajo creation story tells how The People emerged through a series of imperfect worlds. From a First World black as wool to a second, third, and fourth realm, First Man and First Woman led Navajos to this world where beauty surrounds them. Not all the boys boarding the train for boot camp in San Diego believed the old story. Nevertheless, the Code Talkers, switching from hogans to Quonset huts, stood at the rim of one world looking into another.