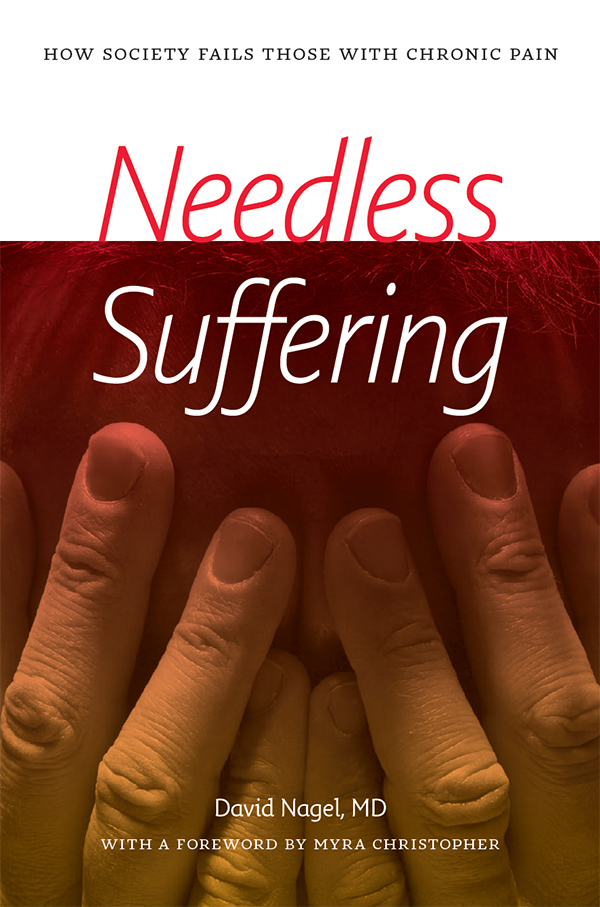

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all those who made this project possible.

I would like to begin by thanking Dr. Richard and Florence Nagel, my mom and dad. In addition to being wonderful parents, they also showed me how to live a dignified life despite pain and disability.

I would like to thank my wife, Mary, and my sons, Tommy and Andrew. Their never-ending support for all I do is inspirational. I also would like to thank Anjali Shah and her family, our extended family in Kolkata, India, who has made the example of Mother Teresa, and so many others who minister to the poorest of the poor, real for me.

I am indebted to all those who have mentored me throughout my personal and professional life; oftentimes the two were enmeshed. It would be challenging to name them all, but many are mentioned in the book. I am most indebted to my patients. In working together to help them overcome their barriers, I have learned much more than I ever could in a classroom. Those lessons have enriched all aspects of my life. Thank you!

I was honored to have attended medical school at the University of Rochester, the only medical school in the United States with a four-year curriculum dedicated to teaching doctor-patient communication, a skill invaluable in my work in pain management. I would like to thank all my mentors, patients, fellow students, and faculty alike, who have helped me become who I am. I would especially like to thank my special mentor, Dr. David Rosen. I learned so much from him. He taught me to use writing as a tool to deal with strong emotion. I took his advice, and I have been writing ever since. It was strong emotion that led me to start writing this book. Thank you, David!

This book, like many of the other stories I have written, began as an emotional catharsis intended for my eyes only. After I had completed what became the prologue and much of part 1, I shared it with Mary Ashcliffe, an author and a chronic pain sufferer. She told me that what I had written was too important not to be shared. She told me I was giving people like her a voice. Thank you, Mary, for the inspiration!

Writing is easy, getting published is not. I would like to thank the folks at the New Hampshire Writers Project, especially Linda Chestney, for your guidance on that step of my journey. I would have been lost without your support. Linda referred me to Jeremy Townsend, who did a wonderful job with the first edit of the manuscript. Thanks, Jeremy!

With an edited version in hand and no clear direction, I fortuitously bumped into Dr. John Butterly. He asked me to send a summary of the book to him, which he shared with Phyllis Deutsch at University Press of New England. I would like to thank both of you for your support. What you have done means the world to me and so many others.

Phyllis referred me to Stephanie Golden to edit and prepare the final manuscript. Stephanie did a wonderful job, and I will greatly miss our weekly, sometimes daily e-mails, which helped keep me concise and focused, two skills I am lacking. I am forever indebted to her.

I would like to thank my friends Pat DAmbrosio, Gail Petterson, and Cindy Steinberg for reviewing the manuscript. I would especially like to thank Myra Christopher, the director of the Pain Action Alliance to Implement a National Strategy (PAINS), for her friendship and support. Throughout this project, I felt like a meek voice crying out in the wilderness on behalf of the patients with whom I work. Myra truly believes that all voices, big and small, have value and should be listened to. Thank you, Myra, for reviewing my work, listening to me, and supporting me!

ONE

A Young Doctor Transformed by a Man in Pain

Pain is the most terrible of all the lords of mankind.

Albert Schweitzer, On the Edge of the Primeval Forest

The year was 1986. I was a resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation and had been asked to see a man who had recently had back surgery.

Have fun, my colleagues joked. Nothing like wasting time on a chronic painer! Those back patients were all the same, werent they? Just lazy people looking for a ticket out of their responsibilities. X-rays all negative. No objective explanation for their pain. If they only got off their butts and lost some weight, they would be fine. Why did they have to waste my time? I had more important things to do than treat people who werent going to get better no matter what I did. All they wanted were drugs. At least, thats what my professor said.

I hardly thought that my encounter with Mr. Smith would change my life.

The Veterans Administration hospital where I was training was very large, and it was a long walk to this mans room. I purposely made the walk longer, for I dreaded what was at the end of it. But eventually, I arrived at his room and reluctantly entered. It was one of the old VA four-bed rooms with flimsy yellow curtains separating the beds. I looked for bed B, saw the patient, Mr. Smith, and watched him for several moments.

Mr. Smith lay uncomfortably in his bed. Every few minutes he shifted in agony. Then he was still, the grimace on his face replaced by a look of fear. What did he fear, I wondered? Several minutes later, the agony reappeared; his face contorted in a manner only pain can produce.

At first, I was suckered into this performance. Who could fake such an act? But the doctors who had operated on him told me nothing was wrong, and it was my job to get him off his butt and out of the hospital. They couldnt be wrong, could they? I didnt know it, but I was caught in a battle. Whom should I believe, patient or doctor?

I sat down next to the man, coldly introduced myself, and dutifully began to take a history. Hello, Mr. Smith. I am Dr. Nagel, and I am here to help get you back on your feet, I said with no enthusiasm. Mr. Smith showed little acknowledgment of me. He continued to alternate between expressions of fear and agony. But as we talked, his story unfolded.

Mr. Smith was forty-seven. He had been born in the same city and with the same hopes as me, maybe even at the same hospital. His parents didnt have a lot of money, so he had to work after school. Up at 5:00 AM to do homework, off to school, then to work, and back home by 10:00 PM five days a week. He worked on Saturdays too. His job was physical, and pain was a part of his life. School didnt offer him much, so he left to work full-time. When he turned eighteen, he joined the army. He served in Korea and returned with medals. He was a hero, but he didnt have time to relish his accomplishments. Medals look good on shelves, but they dont pay the bills.

He returned to work. The best jobs were at the steel plants. They were physically demanding, but the pay was good. At twenty, he was a war veteran and a work veteran. At twenty-one he had his first back injury. He ignored it. Pain was part of life, and a hard worker had back pain. It was a medal, an award for his labors. Over the years, though, the pain increased. At first, it was just in his back. Then it started to go down his leg. First it was just a little numbness, but then an electrical fire shot through him that tore at his soul.

He had never been to a doctor in his life. Pain is part of life, he kept telling himself, but over time he believed this less and less. He decided his pain was one medal he wanted to send back. Disabled by pain at twenty-five, he wanted to see if the doctors could help him.

The doctor he saw was very supportive. After an examination and tests, he told Mr. Smith he had a ruptured disc. All he needed was a simple operation, and hed be back to his old self in no time. He was told he had a 99 percent chance of being cured. Mr. Smith thought those were pretty good odds. He told his boss he needed an operation, and hed be back soon.

Next page