Our hearts ache, but we always have joy. We are poor,

but we give spiritual riches to others.

We own nothing... yet we have everything.

Paul(2 Corinthians 6:10 NLT)

The glory of God is humanity fully alive.

Irenaeus

The more humility aims at the depths, the higher

it climbs on the path to the summit.

Gregorythe Great

Rest assured of the truth of a saying that seems paradoxical, that he who hurries delays the things of God.

Vincentde Paul

Christians live with a constant paradox. They have

come home, but they are on a journey. They are freed

from sins power, yet daily confess their sins. They have

received eternal life, yet wait for the age to come.

CharlesR.Ringma

Foreword by Gerald R. McDermott

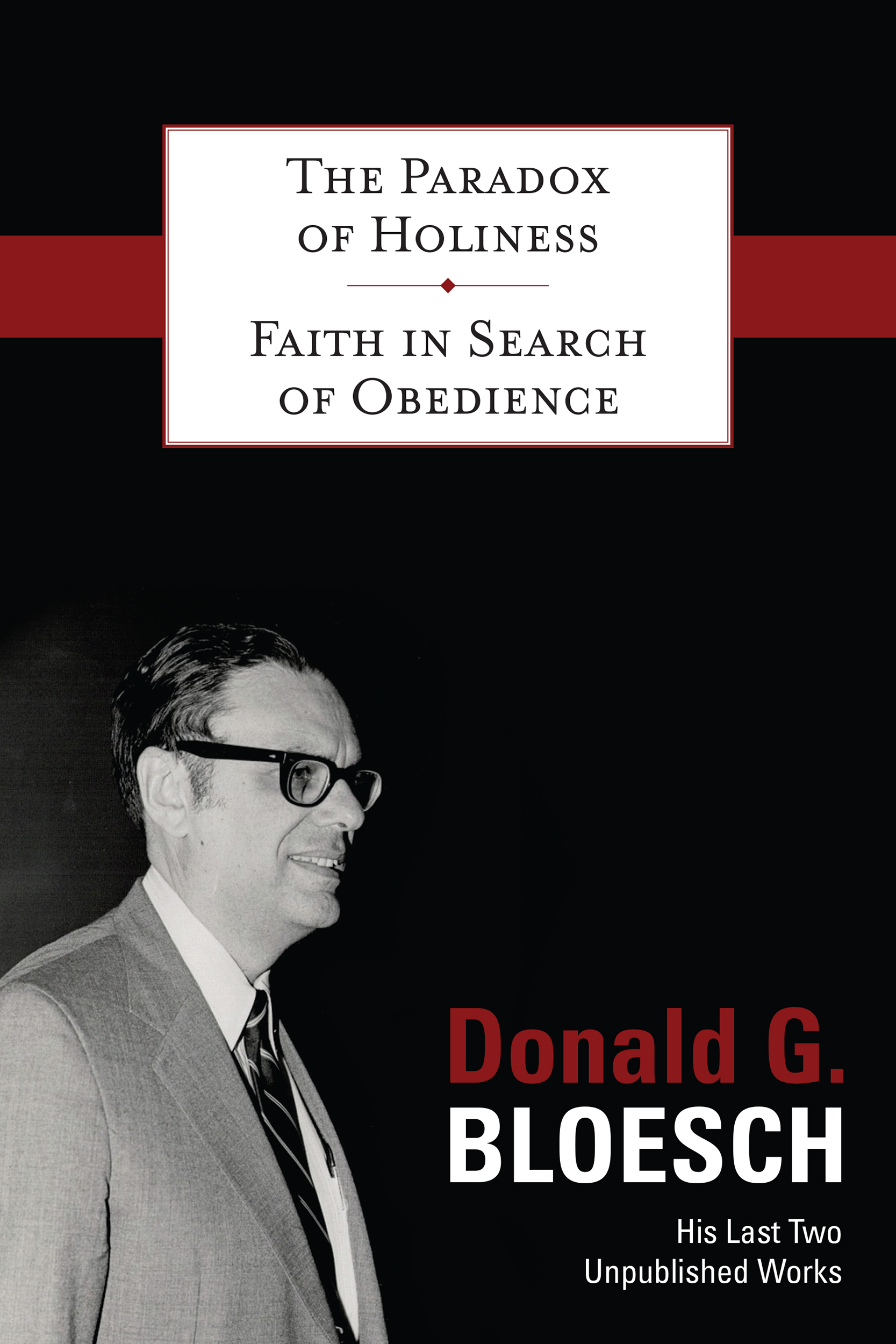

Michael McClymond has remarked that the only theologians worthy of deep study are those who are also saints. One thinks immediately of Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and Jonathan Edwards. I would add Donald Bloesch.

I first met Bloesch when I was in graduate school at the University of Iowa. I remember being one of several PhD students invited by Dr. Bloesch and his lovely wife Brenda to their home for dinner, and then to hear him lecture at a nearby college. One of my friends struggled with his advisor and committee at Iowa, and Dr. Bloesch, who had taught there for a semester, intervened on his behalf and shepherded him through a long ordeal. From my friends who had been to Iowa before me, I heard story after story of the kindness and sacrifices Bloesch had expended for students, colleagues, and assorted souls wrestling with the vicissitudes of life.

Bloesch helped me through my own theological vicissitudes. As I struggled to find the meaning of Christian orthodoxy, I turned so often to his Essentials of Evangelical Theology that my copies of those two volumes are now dog-eared. Shortly before his death, I asked him to write an essay on justification and atonement for The Oxford Handbook of Evangelical Theology. As always, it was balanced and wise, advising that atonement in the Bible represents much more than the forgiveness of sins... [but also] liberation, acquittal, regeneration, satisfaction, expiation, propitiation, and certainly also sanctification. This was an important word when much of Protestant theology limited the meaning of justification to pardon.

Donald Bloesch unabashedly called himself an evangelical when it was unpopular in the academy to do so. When evangelicals themselves debated whether the term had clear meaning, Bloesch fought to reorient its meaning by teaching them and the wider world to return to the enduring visions of the Reformers and the church fathers.

These visions, recaptured by Bloesch, are timely for our troubled church and world. When some Christians reduce the gospel to a declaration of forgiveness, Bloesch reminds us of the inseparability of orthodox doctrine and holy living. As he put it (in one of his countless pithy and memorable expressions), Sin is behind us but righteousness before us.

But righteousness, he warned, must beware of being merely social, and it must not try too hard to be relevant. The gospel contains its own relevance. Faith, he urged, resists accommodating truth to social programs. Gods revelation might strike some as insensitive to todays cultural orthodoxies, but Bloesch advised that altering the form of revelation risks altering its content. Truth must never be sacrificed at the altar of unity. Greater than the sin of disunity, he cautioned, is the sin of disloyalty to the Scriptures and the Lord of the church.

These words of wisdom, which run throughout these two last works of Bloeschs fertile career (over four hundred publications, and without a computer!), are the perfect medicine for todays ailing evangelicalism. The very last work is his spiritual autobiography, Faith in Search of Obedience. One of its recurring themes is the course evangelicalism must take if it is not to go the way of all flesh.

First we should be reminded, he avers, that good theology is reflection on Scripture and that our best commentaries on Scripture come from the church fathers and the Reformers. Evangelicals can also learn from Pietism the necessity of costly discipleship and the need for life in the Spirit. But they should beware that rationalism and Pietism are not necessarily antithetical, for both are focused on the human response to God rather than Gods revelation. They should adopt a theology of Word and Spirit rather than a theology of experience (pietistic subjectivism) or moral commitment (liberal moralism).

Yet Bloesch was not uncritical of the Reformers. He believed that Luther was wrong to put law before gospel, for he learned from Barth that the law itself was a giftafter the gift of the Exodus. From Barth he also learned our need to subordinate subjective experience to Gods objective revelation. Yet at the same time, Bloesch warned that Barth wrongly taught an incipient universalism and could be perilously anti-sacramental.

From Reinhold Niebuhr, Bloesch learned the dangers of pacifism. As he put it so memorably, love without power surrenders the world to power without love. Niebuhr also taught Bloesch the importance of public theology. The voice of faith, Bloesch proclaimed, should never be excluded from the public square. Public policy must never impede the evangelical thrust of the churchs message.

In a day when the meaning of marriage is so sharply contested, these last works portray the beauty of biblical marriage. Donald and Brenda steered a way between patriarchalism and feminism. Holding a PhD herself (in French literature), Brenda was his helpmeet and theological partner. Both believed in women in ministry. She reproved and instructed her husband, and he instructed husbands to always listen to their wives.

Both Kierkegaard and Solzhenitsyn observed that courage is rare in the modern world. Yet Bloesch exemplified it. He was not afraid to present a paper on the reality and theological importance of the devil to a liberal faculty, one of whom walked out of the room. At a faculty-staff retreat he boldly lectured on the second coming of Christ, knowing this might not be appreciated by his colleagues. He regularly spoke at regional and national meetings dominated by liberal theologians on themes that challenged their presumptions. That same boldness characterized his ministry in the church. He insisted that godparents to a baptized child be God-fearing, and lost some church members as a result. Three times he walked out of evangelical services that he felt were exalting the preacher rather than our Lord.