For my parents,

Douglas Keith and Jean Margaret Barrett

Contents

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicized Catholic Edition, copyright 1989, 1993, 1995 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

How do you cope with Psalm 78? the young nun asked me.

I promise you, not every conversation between Benedictine nuns and monks has to do with sacred texts and spiritual aspirations. We can time-waste in gossip along with the best. But this question, asked some 40 years ago, came from one monastic newcomer (or novice) to another, and novices tend at least to aim for more edifying discussions.

Psalm 78 is the longest account of Israels sacred history in the Old Testament Hebrew hymn book, the psalter, as the book of Psalms is often called from its Latin title psalterium . Give ear, O my people, to my teaching; incline your ears to the words of my mouth, the psalm begins (Ps. 78.1). One point being made by that young nun is that, with it being 72 verses in total, inclining ones ear to the entirety of Psalm 78, to say nothing of lending ones mouth to its words to recite them in choir, is a significant test of any novices monastic endurance. Israels desert wanderings took Gods people 40 years, we are told. This psalm, when you first meet it full-length in worship, can seem to be taking at least as long. Are we there yet? the heart murmurs.

Monastic men and women spend more hours of the day sitting with the psalms than we do in most other activities. I suppose you might call us professional psalm-singers. So it is very far from unreasonable for one monastic to ask another about how he or she approaches prayer with the psalms. Its the kind of necessary specialist conversation that, between those with a passion for any endeavour, indicates a healthy approach to improving an individuals skills in their chosen field; a good thing in most peoples books.

And so, when I was asked about the challenges of approaching this lengthy psalm, I might for example have pointed my novice friend to Psalm 78s opening words Give ear to my teaching, echoed very directly in the first words of the Rule of St Benedict: Listen, my child, to my teaching, and incline the ear of your heart. One way to appreciate the psalms is to recognize the various ways in which their perspectives, language and images inform so much of our Christian tradition, including the Rule, or way of life, written for monastics in the sixth century by St Benedict of Nursia; the classic Christian text that continues to inspire the life of Benedictine monasteries to this day.

Alternatively, my answer that day might have targeted the colourful imagery of divine action bringing help to Gods chosen ones that runs through the psalmists account of Israels desert journey. In Psalm 78, God and Gods chosen people Israel are portrayed in a species of salvific dialogue, with the whole natural order becoming the vehicle of that conversation. And so, in this psalm, when the wind blows it does so because it was summoned by God to bestow the blessing of food in the wilderness on a hungry nation:

he sent them food in abundance.

He caused the east wind to blow in the heavens,

and by his power he led out the south wind.

(Ps. 78.25-26)

The dry, desert landscape through which Gods people venture is suddenly watered by fountains springing from the rocks, shattered by earthquake at the Lord Gods command:

He split rocks open in the wilderness,

and gave them drink abundantly as from the deep.

He made streams come out of the rock,

and caused waters to flow down like rivers.

(Ps. 78.15-16)

And, through the trackless wilderness, the compassion of God blazes like a column of raging fire ahead of his chosen, guiding them towards their ultimate destination:

In the daytime he led them with a cloud,

and all night long with a fiery light.

(Ps. 78.14)

The attitude of attentive listening, of receptivity before Gods word, inculcated by our centuries-old Benedictine way of life; the capacity of the language and imagery of the psalter, the Book of Psalms, to perform evocatively by stirring up a great wind from God, breaking open a fountain of living water within our hearts, inflaming us with a fire that cannot be easily quenched these might have offered me the beginning of an answer when I was asked about Psalm 78. But to my embarrassment, I had to admit to the novice nun that my own monastery did not attempt to cope with Psalm 78, whole and entire. At that time, it was delivered to us in bite-size portions, spread over several days, and then only during Lent. As a consequence, I really had never thought about the wider implications of the question she was asking. I wont tell you what my interlocutor said in response to that. Suffice it to say that any emerging aspiration on my part to guru status was rapidly and quite rightly dismissed.

More recently, my brethren and I have mended our ways. We now trek through the full extent of this psalmic tale of Israels infidelity to our faithful God throughout the year, on every other Thursday morning though we do take a brief pause about halfway through Psalm 78 in an attempt, not always wholly successful, to get the reciting note back up again. Now that I do have a regular experience of attempting to cope with this demanding psalm, I can (somewhat belatedly) attempt the answer I should have been ready to offer forty years ago to my fellow monastic novice. This book is a version of that answer; though I must allow that the answer has now grown a fraction longer than it might have been all those years ago! And I suppose it has done so not least because I write now with an awareness that it isnt only the professional psalm-singers of our monasteries and religious houses who may struggle from time to time to find their way into some of our sacred texts. I hope that readers who perhaps have less time to spend among the psalms and the rest of scripture than we nuns and monks have in our monasteries may find something of value in the pages that follow.

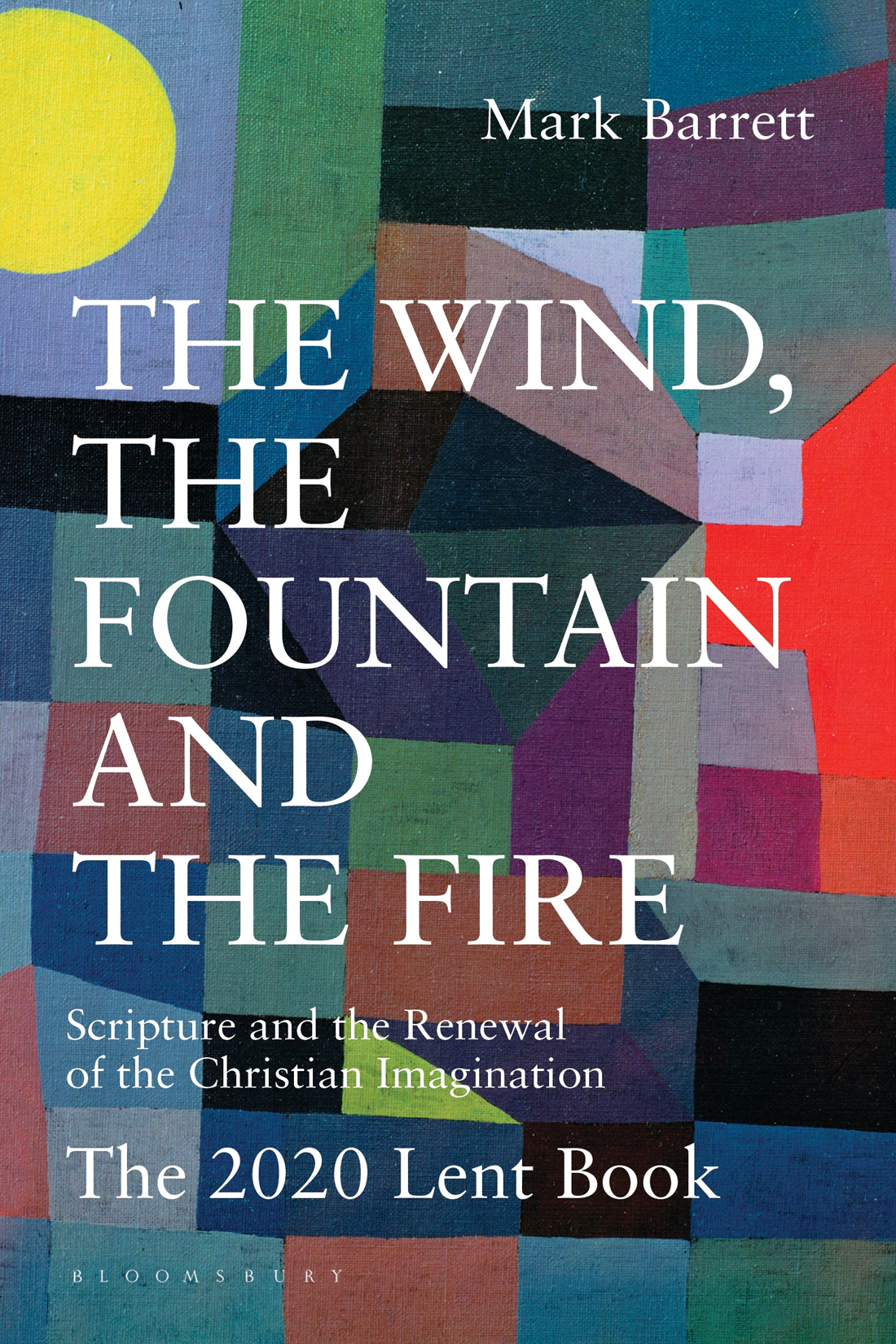

In The Wind, the Fountain and the Fire I invite you to join me in noticing in the psalms and more widely across the pages of the Bible particularly the magnificent sequence of Lenten Sunday Gospel texts some of the things it would have helped me to be aware of when I was asked about praying with Psalm 78, 40 years ago. The question I ought to have been asking is: how does any of us find her or his way into scriptural texts? Where do we discover the wind of the Spirit, the fountain of living water and the fire from which God speaks, among the printed pages of our Bibles? Looking back, I realize that it is the regular practise of psalmody singing the psalms in community along with a daily attending to the sacred reading of scripture during worship and in personal prayer, that rubs away at the edges of my ignorance, slowly eroding some of my hardness of heart. Repetition opens doors. One of the ways that it does this, I now appreciate more fully, is by bringing my experience of praying the psalms right up against my reading of the rest of the books of the Bible, especially the New Testament and the Gospels. The images and word-pictures I encounter throughout the day in the psalms I sing among my brethren in the monastery choir resonate with the central themes of Jesus message of salvation in the Gospels; at the same time, the Gospel sayings and actions of Jesus are reflected back onto the texture of our psalmody, enriching and renewing its ancient insights.