All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Due to technical issues, this eBook may not contain all of the images or diagrams in the original print edition of the work. In addition, adapting the print edition to the eBook format may require some other layout and feature changes to be made.

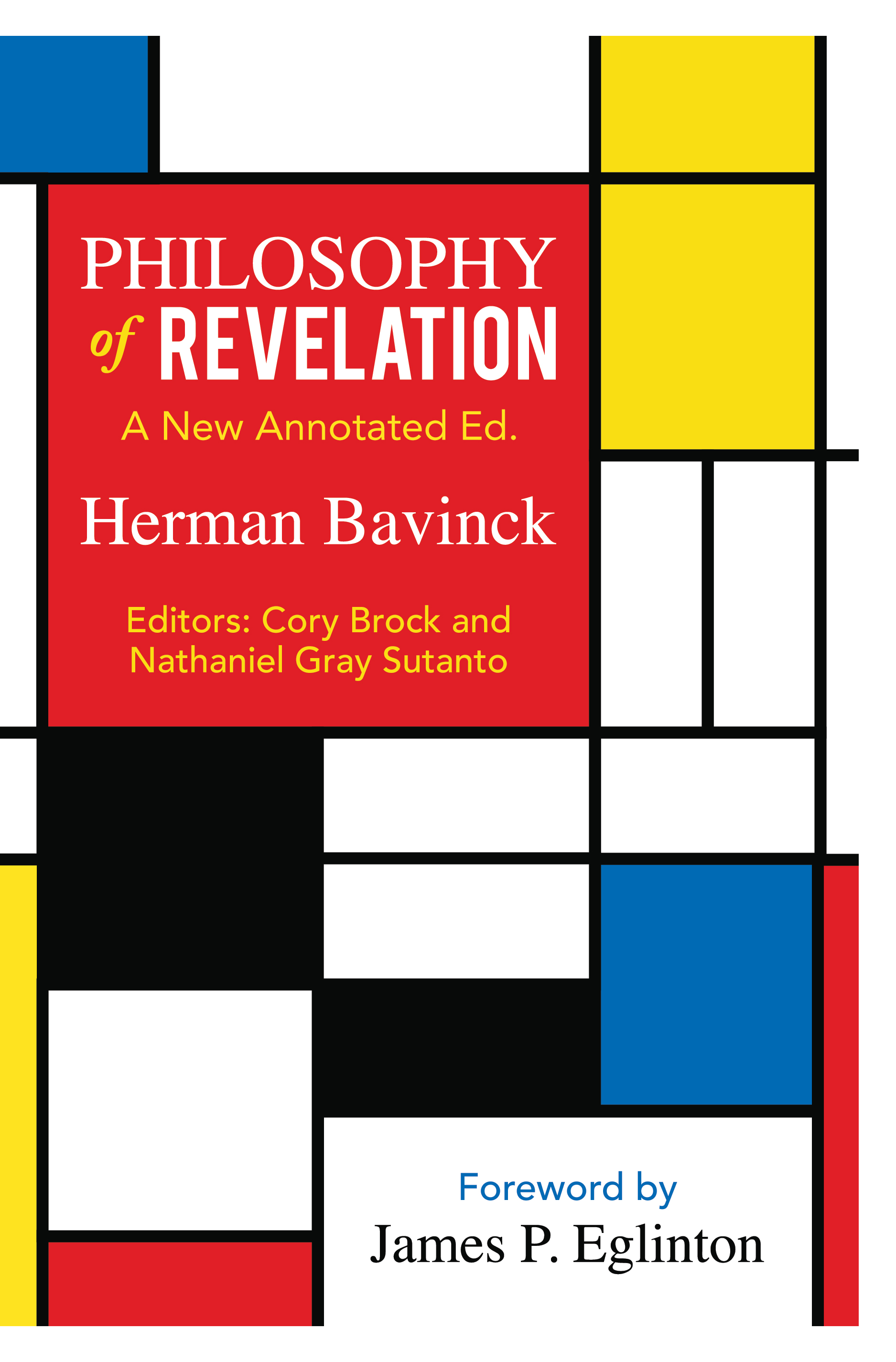

F oreword

This new edition of Herman Bavincks Philosophy ofRevelation, carefully revised by Cory Brock and Nathaniel Gray Sutanto, is a timely publication. In the century since the books first appearance, the heyday of late modern Western culturewhen supremely confident human knowers went about their task of grasping a comprehensible, orderly worldhas run its course and given birth to a new age. In the present day, cultural natives find the Western world as an altogether more chaotic, discordant place. It is a scene of profound and painful social divisionsclass-based, political, cultural, racial, and generational, among otherswhere imaginings of the past and visions of the future jostle endlessly to nobodys great satisfaction.

Against that backdrop, the great questions at the heart of Philosophyof Revelation remain pertinent, albeit taking on a twenty-first-century flavor: How should we understand the world and our place within it? Is such an understanding even possible, given the dampened epistemological self-confidence that pervades twenty-first-century Western culture? What of the Dawkinsesque claim that the natural sciences are the bestor perhaps the only reliableway to understand the cosmos and all that is found therein? Should we expect the natural sciences to provide a rich and satisfying account of life in its entirety? In an era where revived populist nationalisms set themselves against liberal progressivism, how ought we to understand the existence and development of human culture in this world? Is progress self-evidently good or inevitable? Are progress and regress in any sense useful terms? In that light, is it possible to think meaningfully about either history or the future? Why, despite the dire prognosis afforded to religion in the late nineteenth century, does religiosity remain the norm rather than the exception across human cultures in the present day? (And from this, the supremely Christian concern remains: What is the significance of Jesus Christ in the Wests current cultural iteration?)

In this book, Herman Bavinck advances an argument of stark consequence for present-day readers: namely, that the deep issues undergirding these questions (an account of humanity and the world, God, history and progress, science, and the power of religion) must be answered to our satisfaction if our lives are to be well lived. Should we fail to do so, Bavincks logic implies, we will remain locked in the existential and intellectual ennui that marks our secularized age. This implication flows from Bavincks belief that the search for all knowledge is, at heart, a ceaseless effort to understand the relationship between God, humans, and the worldan undertaking that necessitates and births the aforementioned questions.

God, the world, and humanity are the three realities with which all science and all philosophy occupy themselves. The conception which we form of them, and the relation in which we place them to one another, determine the character of our view of the world and of life, the content of our religion, science and morality. (70)

For Bavinck, to ignore any of theseor to treat them as unanswerable, as is assumed by some streams of twenty-first-century thoughtis inherently existentially unsatisfying. To do so is to neglect the greatness of the human spirit, which longs for a satisfying knowledge of who God is, who we are, and how we should exist in this world.

How did Bavinck direct his early twentieth-century readers in answering these questions? Where were they to begin in search of a satisfying knowledge of the world and their place in it? This book is an extended argument for the necessity of revelation in making sense of life in the world, and God, to our own satisfaction. Echoing the classically Augustinian desire to know both God and self, Bavinck argues that our search for a fulfilling knowledge of ourselves and our world must begin with Gods own knowledge of himself. As God knows himself perfectly and fully, and finds this self-knowledge to be delightful, God chooses to share it in an act of self-disclosure. God reveals what would otherwise have remained a mystery to us: the love, infinity, simplicity, glory, perfection, complexity, and unity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

For Bavinck, this process of revelation should be viewed along two lines. Generally, God is revealed in the origin and ongoing existence of the universe itself. The cosmos is a general revelation of God. Macro- and microcosmically, the world itself makes known to us the power of [Gods] mind (25). Alongside this, God also practices another form of self-disclosure, which Bavinck sees as special revelation. This form of revelation, which centers on God as made known in Jesus Christ, functions as a disclosure of the greatness of Gods heart (25) . We can know that our Creator loves us, because he tells us so quite explicitly.

In both forms of revelation, Bavinck believed that God reserves the exclusive right to define himself and his actions, to grant purpose to the universe, and to tell us who we are. For Bavinck, this knowledge is indispensable to the human quest for existential and intellectual satisfaction. A twenty-first-century reader might ask: What about those who profess no belief in God? How does Bavincks assertion relate to those whose worldview is founded on naturalism, and who want to answer the great questions of life without recourse to the supranatural? Might it not be possible to develop satisfying answers to these questions by starting (and concluding) with ourselves and our world, rather than beginning with a seemingly abstract and distant notion like Gods knowledge of himself?

To this, Bavinck responds that all people live out a functional, if not intentional, dependence on Gods self-revelation. This leads Bavinck to portray life lived in denial (or ignorance) of the reality of divine self-disclosure as necessarily fractured, in contrast to the blessed life that acknowledges revelation. No one, Bavinck argues, lives consistently with the idea that there is nothing beyond the natural world and that revelation from the outside is an utter impossibility. Rather, those who profess the creeds of strict atheism and naturalism nonetheless live out a de facto reliance on the reality of revelation. Humanity, no less than formerly, continues to live and think after a supranaturalistic fashion (17) . However, while most people approach the great questions of God, the self, and the world in ways that assume (rather than deny) the reality of revelation, fewer consider the importance of revelation deeply enough to render their experience of life as beautiful in its coherence. In that light, this book should be read as a search for the good life. It is a pursuit of that which will satisfy heart and mind, conscience, and will.