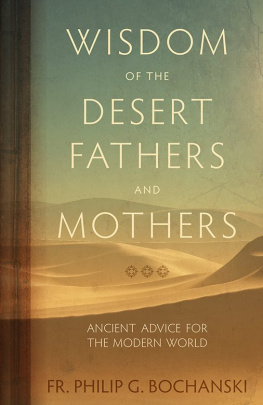

The Wisdom of the Desert Fathers and Mothers

2010 First Printing

Copyright 2010 by Paraclete Press, Inc.

ISBN 978-1-55725-780-2

Unless otherwise designated, Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.

All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Scripture quotations designated ( KJV ) are taken from the King James Version.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data

The wisdom of the Desert Fathers and Mothers : contemporary English version / [translated] by Henry L. Carrigan, Jr. : foreword by Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-55725-780-2

1. Spiritual lifeChristianity. 2. Anthony, of Egypt, Saint, ca. 250-355 or 6. 3. Paul, the Hermit, Saint, d. ca. 341. 4. Desert FathersBiography. I. Carrigan, Henry L., 1954- II. Athanasius, Saint, Patriarch of Alexandria, d. 373. Life of St. Antony. English. III. Jerome, Saint, d. 419 or 20. Vita Pauli. English.

BR63.W57 2010

248.470922394dc22

2010022514

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts

www.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I f books could be weighted according to the power of their words, you wouldnt be able to hold the volume that is now in your hands. Given the cost of printing books, we can all be grateful that its available in paperback. But the wisdom printed on these pages is the kind of thing humans have historically written on stone. This is a heavy book.

I say this because I didnt know what I was getting into the first time I encountered Antony of the desert. When his biography was assigned to me in an undergraduate class on Christian classics, I remember feeling relief that it was so much shorter than Augustines Confessions. I was looking forward to a light evening of reading. But I did not get very far into this story about a man who heard Jesus words to the rich young ruler and decided to obey them himself before I forgot what time it was. I remember leaning expectantly over the pages as I tried to make sense of wrestling matches with demons and the rigors of ascetic practice for the sake of drawing near to God. When Antonys friends dragged him from his cell after twenty years, I sat in wonder that he was a picture of health with power to heal and raise the dead. Here was a human being transformed. I sat up half the night, reading that description over and again.

A son of Southern Baptists, I grew up going to revival meetings where some of the best storytellers in the world told me the story of Jesus. By the time I was seven, I was so captivated by the power of Jesus that I promised him my whole life. My pastor told me it was the most important decision I would ever makethat this one choice changed everything. But a decade later, when I was a student on a Christian college campus, I was disappointed by how little had changed. Could Jesus really make me into a whole new person?

Antony gave me hope that a new life in Christ was possible. But he also showed me, in no uncertain terms, what new life would costnothing less than everything. I was scared to death, but I was also unexplainably attracted to this person. Like Nicodemus who came to Jesus in the night, I wanted to slip away and listen to this man.

In time I learned that I was not the first to have this feeling. When word got out about Antonys transformation, the desert became a city. Those who came proved that Antony was not an exception. Devoting themselves to a life of prayer and the hard work of stability, a whole host of men and women grew in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine, Syria and Turkey to become wise mothers and fathers in the faith. They gathered themselves in communities called lauras and sketes. When hungry souls came looking for a word, they listened prayerfully and spoke succinctly. The sayings collected here under the names of those who said them are the sound advice that folks took home with them. I doubt they wrote them down immediately. These are the sort of words that, if you really hear them, you dont have to write them down. They stay with you forever.

The heart of desert wisdom, just like the heart of Jesus gospel, is in the memorable images and words of instruction that came in short sayings from the ammas and abbas. But just as Peter, Paul, and John wrote reflections to help us make sense of the sayings of Jesus, more systematic thinkers came along to make sense of the desert wisdom also. Evagrius and John Cassian are the best known of these scholars. Their reflections help us put the pieces together into a wholethe desert wisdom as a vision for what life with God and other people can be. They are secondary, of course. Without the radical commitment and total abandon of someone like Antony, their work would have never been possible. And yet, without their careful thought, we may well misunderstand the gift of the mothers and fathers. Part of the wisdom of the tradition, I suppose, is that we need experience and reflection, theology and practice.

I live my life with Jesus and other friends in a Christian community that has been described as part of a new monasticism. I never cease to be amazed by how many people in our hypermodern culture of virtual reality show up at our door and dinner table, eager to talk about one thing: how to live the way of life that Jesus taught and practiced. As I pass the potatoes or sit across a cup of tea from these souls, I see a glimmer of hope in their eyes. I suspect its something like the hope I felt that first night I sat up reading about Antony of Egypt. Maybe, I kept thinking, a whole new life is possible. Maybe its already here. Maybe we really can become the church we dream of. Coming back to the words in this book helps me keep hope alive. The church doesnt just believe another world is possibleweve seen it. If it could happen in the fourth and fifth centuries, it can happen where we are today. May we, by the power of the Holy Spirit, become the new creation we long for.

Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove

INTRODUCTION

T wo of the most enduring images used to describe the Christian spiritual life are the wilderness and the desert. On one level, Christians have used these images to describe spiritual experiences involving feelings of Gods absence or abandonment. Christians often describe their feelings of spiritual loneliness and times of separation from God as periods of wandering in the wilderness. Often these same Christians, feeling that God is somehow testing them as they experience devastating losses, physical pain, or spiritual forlornness, compare their time of suffering to Jesus experience of being tested in the desert.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS