A new idea is first condemned as ridiculous and then dismissed as trivial, until finally, it becomes what everybody knows .

A person experiences life as something separated from the resta kind of optical delusion of consciousness. Our task must be to free ourselves from this self-imposed prison, and through compassion, to find the reality of Oneness .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Heather for being the one next to me when I came up with the idea for this book. And for always being beside me.

And thanks to Bruce Walters who taught me how to see and how to trust what I saw.

I would also like to list the storytellers whose work has inspired, and guided, me over the years. As I began to compile this list, it kept growing, and I became frightfully aware that when this book sees print I will open it, see this page, and slap my forehead because I have forgotten someone.

So let's just say that this is a partial list of some of the storytellers whose work, and/or life, has pointed me in the direction of the Golden Theme.

They are in no particular order, except for Rod. Everything I know about storytelling started with him:

Rod Serling, Edward Steichen, Billy Wilder, Larry Gelbart, Paddy Chayefsky, Mark Twain, Chuck Jones, Reginald Rose, Lorraine Hansberry, Charlie Chaplin, George Orwell, John Steinbeck, Gene Rodenberry, Steven Spielberg, Neil Simon, Theodora Lange, Bill Cosby, George Clayton Johnson, Will Eisner, Gary Ross, Walt Disney, Harvey Bullock, Don Hewitt, Melissa Matheson, Robert Riskin, Stewart Stern, Richard Wright, Martin Ritt, Shirley MacLaine, William Goldman, Albert Hackett, Frances Goodrich, Jonathan Swift, Sydney Pollack, Aesop, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Jim Henson, Ken Burns, John Ford, Thornton Wilder, Frank Capra, James L. Brooks, Jo Swirling, Ray Bradbury, Fred Moore, Jonathan Swift, Robert Benton, Richard Carter, Alan Alda, Jack Kirby, Steven Zallian, John Houston, Bo Goldman, Leonard Nimoy, Glen Keane, Robert Lewis Stevenson, Harriet Frank Jr., Irving Ravetch, Alex Hailey, Ray Bradbury, Sally Field, Frank Darabont, Alfred Hitchcock, Aaron Ruben, Walter Newman, Lawrence Kasdan, Art Spiegelman, Alvin Sargent, and Billie Holiday.

The next sound you hear will be the slapping of my forehead.

FOREWORD

"As a storyteller, you are a servant of your story, not the master. You must do what it requires, not what you want to do. You must remove your ego from it. Art is not to show people who you are; it is to show people who they are."

Brian McDonald

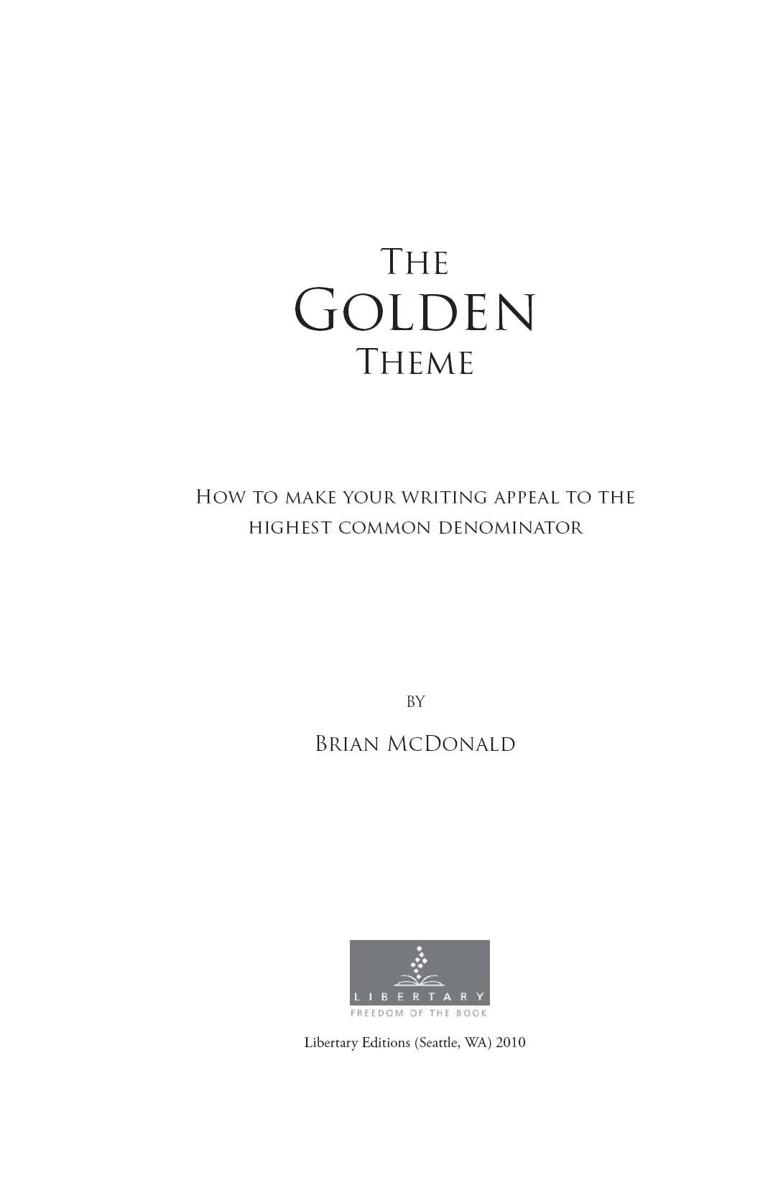

Brian McDonald is one of the world's wisest teachers of the elements that create great storytelling. On this subject, you can trust everything he says, because there is simply no angle or aspect of storytelling what stories mean and our experience of them that he has not deeply reflected upon (and from the standpoint of numerous disciplines in the sciences and humanities), then drawn a conclusion that we can take to the bank.

I've had the genuine pleasure of reading both McDonald's Invisible Ink: A Practical Guide to Building Stories that Resonate (Believe me, no one dissects with greater subtlety how great films work their magic) and The Golden Theme: How to Make Your Writing Appeal to the Highest Common Denominator , and also watching his wonderful short film "White Face," a fake documentary about what it might be like if clowns were seen as a race of people. If I had not retired last year from teaching classes on literature and the craft of writing at the University of Washington, I would place McDonald's two books before my undergraduate and graduate students as required reading. Though retired, I still plan to tell everyone I know novelists, short story writers, playwrights, comic book writers, poets, essayists, and screenwriters---about these texts, for in clear, accessible language, with humor and insight and superbly chosen examples, McDonald explains memorably why we, as human beings, need stories for our very day-by-day survival, and why we can discern in the most enduring stories a "Golden Theme" or pattern that is responsible for their power and truth.

For McDonald understands deeply, even profoundly, how it is precisely that "truth" which makes stories "vital to our existence." They entertain, yes, but more importantly, he writes, they deliver important information from one generation to the next, and provide an interpretation of our shared experiences as a species. McDonald sees, as all great writers have, that the "uncultivated, feral story" is all around us all the time in the form of anecdotes, gossip, jokes, legends, histories and news stories, and he brilliantly grasps the link between all these forms, how one can easily be transformed into another. Our everyday lives are their "natural habitat." Put another way, our human minds are hard-wired to shape our experiences into temporal narratives (with beginnings, middles, and ends, and with a conflict that says these events are not pedestrian but instead portray a performer living for high stakes that will speak to your life, so pay attention), placing the buzzing chaos of experience into that pattern in order to conjure sense and meaning from it.

Throughout these entertaining and enlightening books, McDonald's reflections are guided by a spiritual maturity and moral lucidity seldom seen in writing about this subject. Whether he is discussing the role played by mirror neurons in our feelings of empathy; the Golden Ratio; 2,500-year old parables like "The Boy Who Cried Wolf"; ayurvedic medicine in the Far East (stories given to patients to help them heal); or a delightful anecdote "an accidental sociological experiment" about what happened in 1968 during filming for "Planet of the Apes," his great humanity comes singing off these pages. "I once wrote a story where one of the characters was a slaveholder in the American south," he says. "To find this character's humanity was a challenge for me, as I am a descendent of slaves. But I had to imagine myself in the circumstances of my character's world I had to find that part of him that was like me."

There is potentially a Hitler in all of us, asserts McDonald, quoting from Mother Teresa, and we must acknowledge these monsters, this darkness within, when we write. "Beware of people who say, We are different," he counsels us. "Or ones who say, We are better." For in McDonald's view, there are really no heroes or villains in our literature and films, only human beings acting selfishly or unselfishly, and each one of them has something to teach us. Therefore, he offers this smart advice: "Whenever possible, a storyteller should draw a parallel between the hero's weakness and the villain's. That way the audience can measure the triumph of the hero against the failure of the villain with a direct comparison." And perhaps the most important lesson of all in these stories we've told and retold since we became a distinct group of humanoids between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago (i.e., different from the other 22 species of now extinct humans and pre-humans), is that, "Sacrifice is the ultimate expression of the Golden Theme" underlying our tales of wisdom.