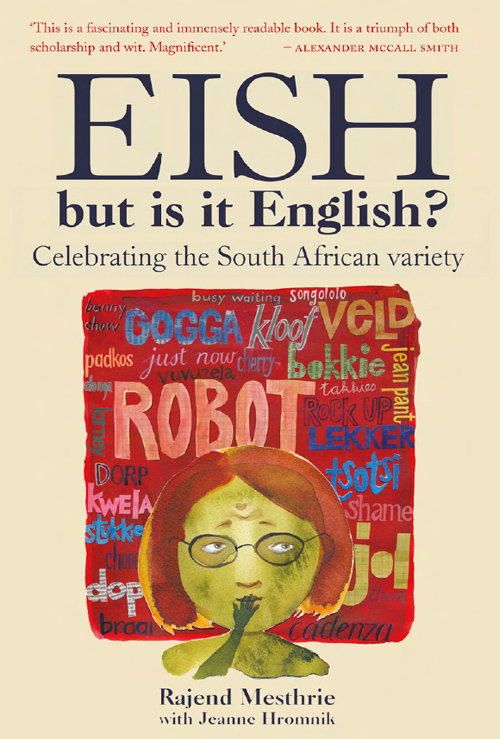

Eish, but is it English?

EISH

but is it English?

Celebrating the South African variety

Rajend Mesthrie

with Jeanne Hromnik

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Street, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000 South Africa

www.zebrapress.co.za

First published 2011

Publication Zebra Press 2011

Text Rajend Mesthrie and Jeanne Hromnik 2011

The extract on pp. 4243 from Mandelas Ego by Lewis Nkosi

is reproduced with kind permission.

Transcription and translation of Generations script: Ramaesela Lekoloane

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER : Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR : Robert Plummer

EDITOR : Beth Housdon

PROOFREADER : Lesley Hay-Whitton

COVER DESIGNER : Doret Ferreira

TEXT DESIGNER : Monique Oberholzer

TYPESETTER : Monique van den Berg

ISBN 978 1 77022 152 9 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 392 9 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77022 393 6 ( PDF )

How this book came about

Jeanne Hromnik

To a degree, although without expectations of equal success, this book was inspired by Lynne Trusss Eat shoots and leaves. Thats not quite the right title, but there is a good chance you might not have noticed. Where Lynne Truss focuses on correctness, albeit in the zone of punctuation, much of the interest in this book comes from incorrectness if there is any such thing (see ). Down south (like our friends in Australia), we speak English a little differently. This depends, too, on which part of the we we belong to.

The main inspiration for this book came, however, from John Orrs popular South African radio programme Word of Mouth, which attracts the earnest (Is it correct to say ?), the angry (Last night I heard a television announcer say ) and the broad-minded (It doesnt matter how people speak so long as you can understand them ). I am a devoted follower of Word of Mouth. In fact, I know many of the answers already especially the easy things, like the difference between which and that, or whether you use the plural or singular form of the verb after nouns like group and team and committee. Of greater interest to me are more difficult questions, such as: What is distinctive about South African English? or Can there be many grammars? or What group of South Africans are you talking about? And, by the way, where on earth does bunny chow come from?

On the basis of Word of Mouth, I decided that my personal candidate for sainthood was South African language guru Rajend Mesthrie, who often features on the programme. He knows a lot of the answers, and when he published his recent book World Englishes (in 2008) with Rakesh M. Bhatt, I knew he was the man to tell me about the English or Englishes that South Africans speak, where they come from and how they fit into the world spectrum of English. To my surprise he is a busy man he agreed and, having given his word, did not go back on it, insisting only on certain conditions.

The first of these was that we would not start before the beginning of the following year (2009). We arranged that I would interview him at two-week intervals over two or three months. It seemed like an easy way of writing a popular book on South African English. Raj (if I may) would speak and I would listen and then transcribe his words.

And that is what we did. He sat and spoke to the microphone and to the windows and the walls and, occasionally, to his recently operated-on left knee. I sat and listened and popped in the occasional question. It was enough to make anyone self-conscious, but he survived and that, after all, was one of the points of this book: how self-conscious are we when we speak? Better put: what register do we (consciously or unconsciously) choose to suit a particular occasion?

It wasnt quite as easy as anticipated. Session One came out as a series of clicks and pauses, although the manufacturers of my recording device, made in China, promised wonderful comfort along with perfect sound effect, extreme stability and smart feature which make it the handicraft of master level. Raj was forgiving of the waste of his time. He is acutely aware of the perversity of recording equipment, having spent much time interviewing the surviving basilectal (very broad) and mesolectal (medium broad) speakers of South African Indian English, as well as speakers of other varieties of English.

Then there was the question of writing out a spoken text. The difference between spoken and written English is an intriguing one. The well-known British linguist David Crystal (one of Rajs own candidates for sainthood) points out in The English Language, one of his numerous books, that although there are many differences between the way grammar is used in writing English and the way it is used in speaking it, there are many styles of language where the boundary between speech and writing almost disappears as when people write material to be read aloud (as in radio plays and news broadcasts) or speak spontaneously so that what they say can be written down (as in dictation or teaching).

The present exercise is a case in point. The text was spoken in order to be written down. The challenge remained, nevertheless, of converting hums and haws, pauses and breaks into commas and semi-colons and full stops, as well as paragraphs (and parentheses). But, with minimum interference on my part, it retains, in my opinion, a spontaneity and naturalness that it would not possess had it been written down in the first place. It belongs, therefore, in the area of informal standard South African English and meets the metropolitan standard the kind of English whose formal models, according to World Englishes (p. 4), are those provided by the radio and television networks based largely in London and US cities like Washington, Los Angeles and (for CNN) Atlanta, though with a much lighter tone.

When it comes to speaking English, South Africans are said to lack confidence. Thus, in The Story of English by Robert McCrum, William Cran and Robert MacNeil, which was first published in 1986, we read: There is a distinctive South African English, of course, but it has lacked the confidence of Australian or New Zealand English (p. 304). At the time this was written, the authors were quoting South African novelist Andr Brink to the effect that a completely new kind of English had emerged in South Africa, influenced by Afrikaans rhythms and syntactical patterns.

Could Black South African English be replacing Afrikaans as a driving force in the patterns that can now be observed in South African English? And what of South African Indian English? How does it happen that, as McCrum et al. put it, in India there are more Indians speaking better English than ever before and more Indians speaking worse than ever before? Is there a parallel with South Africa? The authors of The Story of English relate an interesting anecdote about Mrs Indira Gandhi, who was unable to understand the contribution of an Indian delegate at a meeting and the delegate was speaking in English.