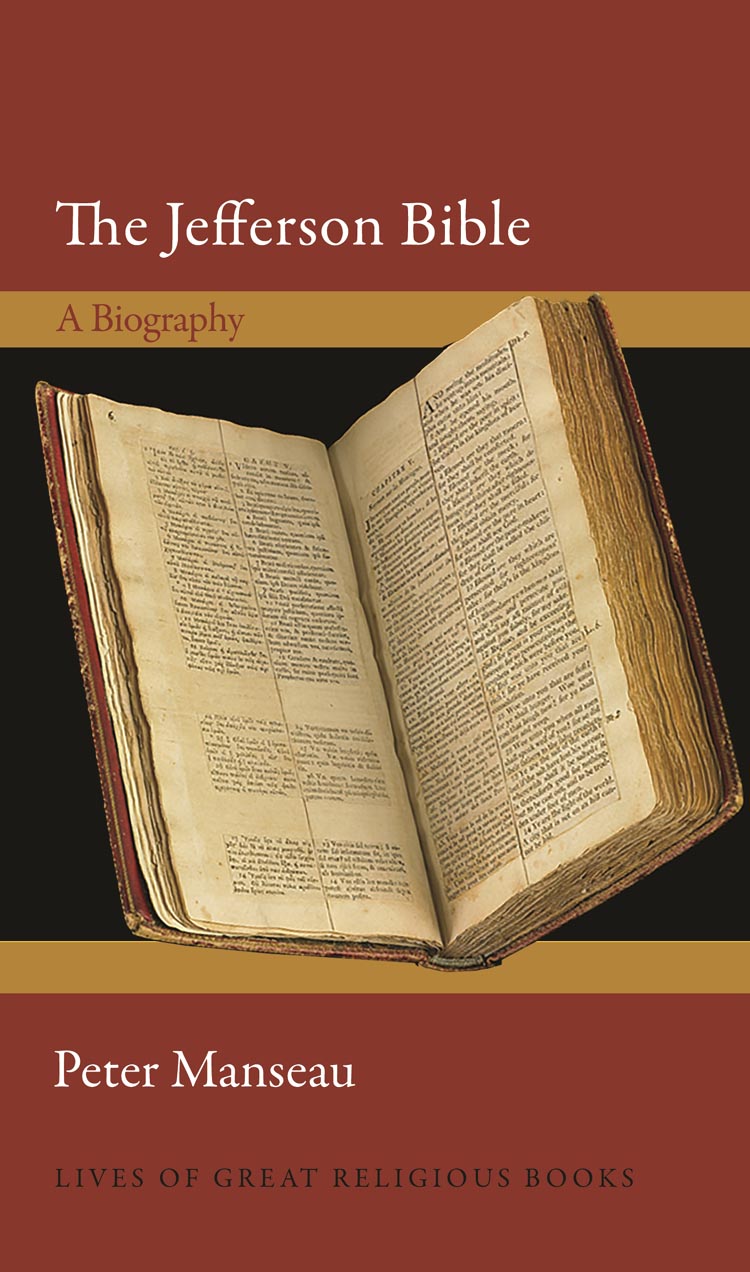

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Jefferson Bible

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Jefferson Bible, Peter Manseau

The Passover Haggadah, Vanessa Ochs

Josephuss The Jewish War, Martin Goodman

The Song of Songs, Ilana Pardes

The Life of Saint Teresa of Avila, Carlos Eire

The Book of Exodus, Joel S. Baden

The Book of Revelation, Timothy Beal

The Talmud, Barry Scott Wimpfheimer

The Koran in English, Bruce B. Lawrence

The Lotus Stra, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

John Calvins Institutes of the Christian Religion, Bruce Gordon

C. S. Lewiss Mere Christianity, George M. Marsden

The Bhagavad Gita, Richard H. Davis

The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, David Gordon White

Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae, Bernard McGinn

The Book of Common Prayer, Alan Jacobs

The Book of Job, Mark Larrimore

The Dead Sea Scrolls, John J. Collins

The Book of Genesis, Ronald Hendel

The Book of Mormon, Paul C. Gutjahr

The I Ching, Richard J. Smith

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Augustines Confessions, Garry Wills

Dietrich Bonhoeffers Letters and Papers from Prison, Martin E. Marty

The Jefferson Bible

A BIOGRAPHY

Peter Manseau

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2020 by thee Smithsonian Institution

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939834

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780691205694

ISBN (e-book) 9780691209685

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Fred Appel and Jenny Tan

Production Editorial: Debbie Tegarden

Jacket/Cover Design: Lorraine Doneker

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: James Schneider and Kathryn Stevens

Copyeditor: Michelle Garceau

Jacket/Cover Credit: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, sample page of four text columns. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

AUTHORS NOTE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Quotations from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources appear throughout the text that follows. While many archaic spellings and dated grammatical choices may read to twenty-first-century readers as errors (particularly the irksome use of its as a possessive pronoun), Ive chosen to reproduce them here as they appeared in the books Jefferson revered and as they flowed from his own pen.

Any other errors that may appear in the text are of course my own. For helping me avoid mistakes of fact or interpretation, I am grateful for the input of many colleagues at the National Museum of American History and the Smithsonian Institution, whose earlier and ongoing work on The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth made this book possible, particularly Senior Paper Conservator Janice Stagnitto Ellis, Manager of Preservation Services Richard Barden, curators Harry R. Rubenstein and Barbara Clark Smith, and Smithsonian Distinguished Scholar and Ambassador-at-large Richard Kurin. I also wish to thank Jack Robertson and his staff at Monticellos Jefferson Library, which maintains the most complete collection of editions of The Life and Morals available and which was essential to my research.

This book would not exist without the keen instincts of Princeton University Press publisher Fred Appel, who heard a short talk I gave on the Smithsonians history with The Life and Morals and suggested it might be a good fit for this series. I am grateful for his encouragement, as well as for the efforts of his talented team, including Jenny Tan, Debbie Tegarden, Lorraine Doneker, Erin Suydam, James Schneider, Kathryn Stevens, and Michelle Garceau.

My thanks also to the Lilly Endowment, which helped create my position at the museum in 2016, and since then has generously supported the examination of religion across the Smithsonian.

Finally, I owe my deepest gratitude to my family, who helped me complete this project in large ways and small.

Just as the many editions of the Jefferson Bible came to be only through the collaboration of the curators, politicians, and editors introduced in the pages that follow, this book is the product of many hands. And so, too, is our everevolving conception of Jefferson himself. As these pages go to press, the nation he helped establish is engaged anew in a reckoning with its past. Inspired by protests nationwide, the long-overdue removal of monuments to the Confederacy has led to reexamination of other dark corners of our history, including Jeffersons conflicted legacy as an architect of liberty who enslaved men, women, and children. While the The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth may not seem to have direct bearing on this legacy, we cannot read it now without asking how Jeffersons willingness to challenge convention in his beliefs complicates the common justification of his failings as unavoidable for a man of his time.

The outcome of the latest reevaluations of Jeffersons memory remain to be seen, yet one certainty conferred by writing about him during a moment of tremendous change is the humility of knowing future generations will craft their own understandings from those we leave behind.

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Jefferson Bible

Excavating the Sacred

INTRODUCTION

Before he had been gripped by a desire to remake his country, young Thomas Jefferson was moved by a different kind of interest in the land of his birth: a hunger to uncover all that might be learned from the American earth. From an early age, he rarely minded getting his hands dirty. In addition to his brief stint as an official surveyor for Albemarle County, Virginia, and the many agricultural experiments performed with the help of enslaved labor at Monticello, Jefferson was known to undertake works of archaeological excavation, putting shovels and pickaxes to the service of science.

As he wrote in the one book he published during his lifetime, 1785s Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson was fascinated by grass-covered mounds called barrows which, he noted, could be found all over this country, including in the rolling Piedmont landscape he had explored since childhood.

These are of different sizes, some of them constructed of earth, and some of loose stones. That they were repositories of the dead has been obvious to all; but on what particular occasion constructed was matter of doubt.

Entwined with legend, lore, and guesswork, theories concerning the purpose of the barrows proliferated throughout the middle of the eighteenth century. Accounts of battles fought in their vicinity inspired the belief among some that these mounds were accidental monuments to the war dead, covered over with soil on the spots where they fell. Others maintained that the custom of the local Monacan people called for periodically disinterring corpses from far-flung graves to be gathered and reburied ritually in a single location which had been sanctified for that purpose. Perhaps the most haunting explanation of the barrows was that they were general sepulchres for entire villages that no longer existed. According to a tradition said to be handed down from the aboriginal Indians, Jefferson wrote:

Next page