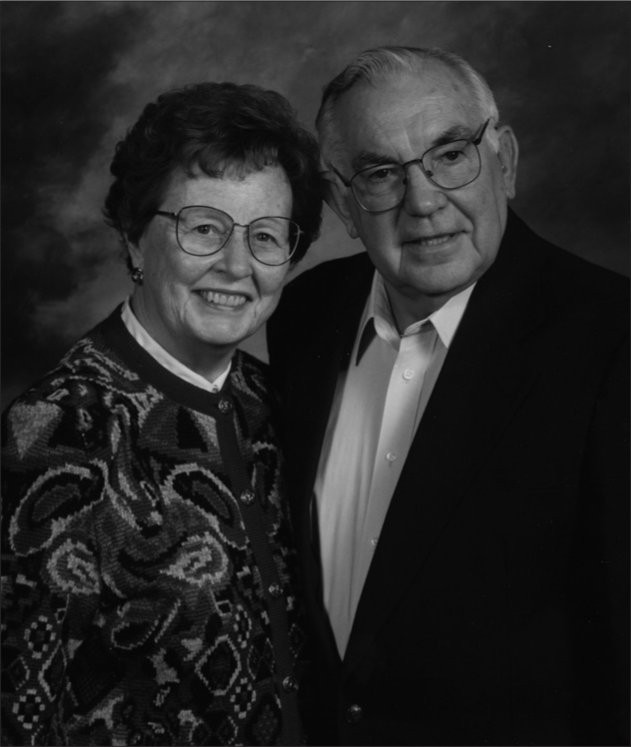

This book is a story of two lives conjoined in love and the pursuit of justice. Their narrative is placed in dialogue with the social history of the times over the past twenty-seven years and depicts the different social projects they have been part of to contribute to the eradication of poverty in Ireland. More recently, they have engaged in a court case seeking justice for themselves. This book describes their formation as theologians and educators, influenced by the liberation thinkers of both disciplines South African, feminist and Latin American and how they used these influences in both their academic and social change work. A community education organisation they co-founded in 1987, The Shanty/An Cosn, thrives to this day.

They outline the place of spirituality in the process of engaging in social change. The book also documents their love story, their reasons for getting married in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 2003 and their search for justice through the legal recognition of that marriage in Ireland. At present, they await the hearing of their appeal in the Supreme Court. The book finishes by including an outline of their method for practising social change which they describe as soulwork in the public sphere.

I recommend this book highly and believe that it will be an inspiration and a resource to many around the world who seek to establish a more just world. The text demonstrates the importance of relationship and attention to the spiritual in order to sustain struggle for societal transformation. The aspiration of this book is clearly to offer an understanding of topics that are not often addressed out loud. I hope that this empowers and sustains those who read it.

My parents married at the beginning of the Second World War, and I was born at the end of it. Perhaps my optimism throughout life can be attributed in part to my arrival into a world that was excavating hope from the rubble of destruction. Although Ireland remained neutral in this war while its neighbours defended their versions of freedom, a canopy of threat still hung like a cloud over the Republic during those six years. In fact, the cloud burst accidentally, at times raining down devastation. The German bombing on the North Strand in May 1941, I was told, was clearly audible from our home across the bay in Nutley Park, South Dublin. There were other bombings too, and I grew up regaled with stories about my parents crouching in the press under the stairs seeking protection during those terrifying episodes.

It is the glance backwards from adulthood that really allows one to assess and evaluate ones childhood. What I experienced then, and what is confirmed by my memories now, is that I had a blissfully happy childhood. My parents simply adored each other. I never once heard an argument or cross word pass between them. My father, Arthur, was a businessman, a confirmed bachelor until, at thirty-three, he unexpectedly met my mother, Imelda, then barely twenty. Marrying my father forced my mother to leave her briefly held job in the Central Bank in Dublin the marriage ban, which prohibited married women from working in the public service, was not removed until 1973.

I recall as a tiny child asking my mother which of the three of us children she loved the most, and without hesitation she responded, I love your father most of all and after that I love each of you equally. When my mother died of cancer in her early sixties, with little warning, many of her close friends confided that she died of a broken heart. It was true. Try as she did, she never got over my fathers death, also of cancer, a few years earlier.

While strongly middle-class, our upbringing was marked by careful expenditure of resources and genuine simplicity. We consumed few goods and services. I have no memory as a child of eating out; however, eating in was delicious as my mother was a wonderful cook and frequently entertained at home. The laughter from their dinner parties and her bridge evenings would ring through the house.

Early on in my life I learned that perceptions of wealth and well-being are relative. At school in Loreto, Foxrock, I had friends who lived in that very affluent suburb of County Dublin. Their fathers were among the industrialists who were reaping the benefit of Irelands break from the cocoon of protectionism led by Sean Lemass. We often attended parties in homes on Westminster Road where butlers and cooks served us and the chauffeur waited on long, winding driveways. All this led me to conclude that our own comforts were few and sparse.

Class distinctions in the Ireland of my childhood were sharp but unspoken. Apart from my grandmothers discourse at every Sunday lunch which always referred to peoples titles and connections, our privilege and others deprivation was never mentioned. Yet, this was a time of marked differences and harsh poverty. Historians remind us that during this post-war period Taoiseach amon De Valera defended the dearth of social services when compared to our northern neighbours on the fact that they paid double the taxes.

Politics were never discussed in our family or within the walls of Loreto, Foxrock, where my sister June and I were educated. My brother Arthur, who also started his schooling in this genteel environment, graduated after his First Communion to the rough and tumble of a Christian Brothers school. However, after a brief sojourn in this ambiance of Republican idealism, he electrified our Sunday lunch conversation on one occasion by asking my father where our grandfather had died. That the response at home, in his bed was wholly unsatisfactory was evident from my brothers crestfallen face. Oh, dear, he stated, I hoped that he died in a ditch fighting for Ireland.

Shortly thereafter he was transferred to a private boarding school in Newbridge, County Kildare, run by the Dominicans. Any socialisation to patriotic hatred was anathema to my father whose manner was marked by a gracious, good-humoured gentleness. This said, one of the most formative stories of my childhood was told by him of his own experience as a boarder in the Jesuit school, Clongowes Wood. Shortly after his arrival there he became aware that a ritual of new boys being severely bullied by older pupils was practised. When the moment came for his initiation, he was prepared. He took a compass from his pocket and drove it through the leg of the leader of the gang. They fled and never touched him again. He quietly added a codicil to this story: Never tolerate an injustice, a phrase that has profoundly influenced my life.

The Catholic Church commanded absolute obedience from its members during this period, and I was among its servants. From my earliest years I had a deep sensibility for the spiritual dimensions of life. I loved solitude, and, reflecting back on my early childhood, I remember thinking a lot about questions related to life and death, and, indeed, pre-life and after-death issues.

My mother had a quiet piety. Her yearly visits to Lough Derg on a penitential pilgrimage involving quite a bit of hardship, our family outings to visit her beloved sister, Mother Dolorosa Gately, in a convent in far-flung Wexford, and her rosary and prayer books beside her bed all had a formative influence. My Dad, on the other side of the bed, muttered, as he smoked his pipe, that she did the praying for all of us. He read from his large pile of history books as she said her rosary. In fact, he offered a perfect antidote, balancing her devotion with scepticism, if not agnosticism, in relation to all dogmatic absolutes.