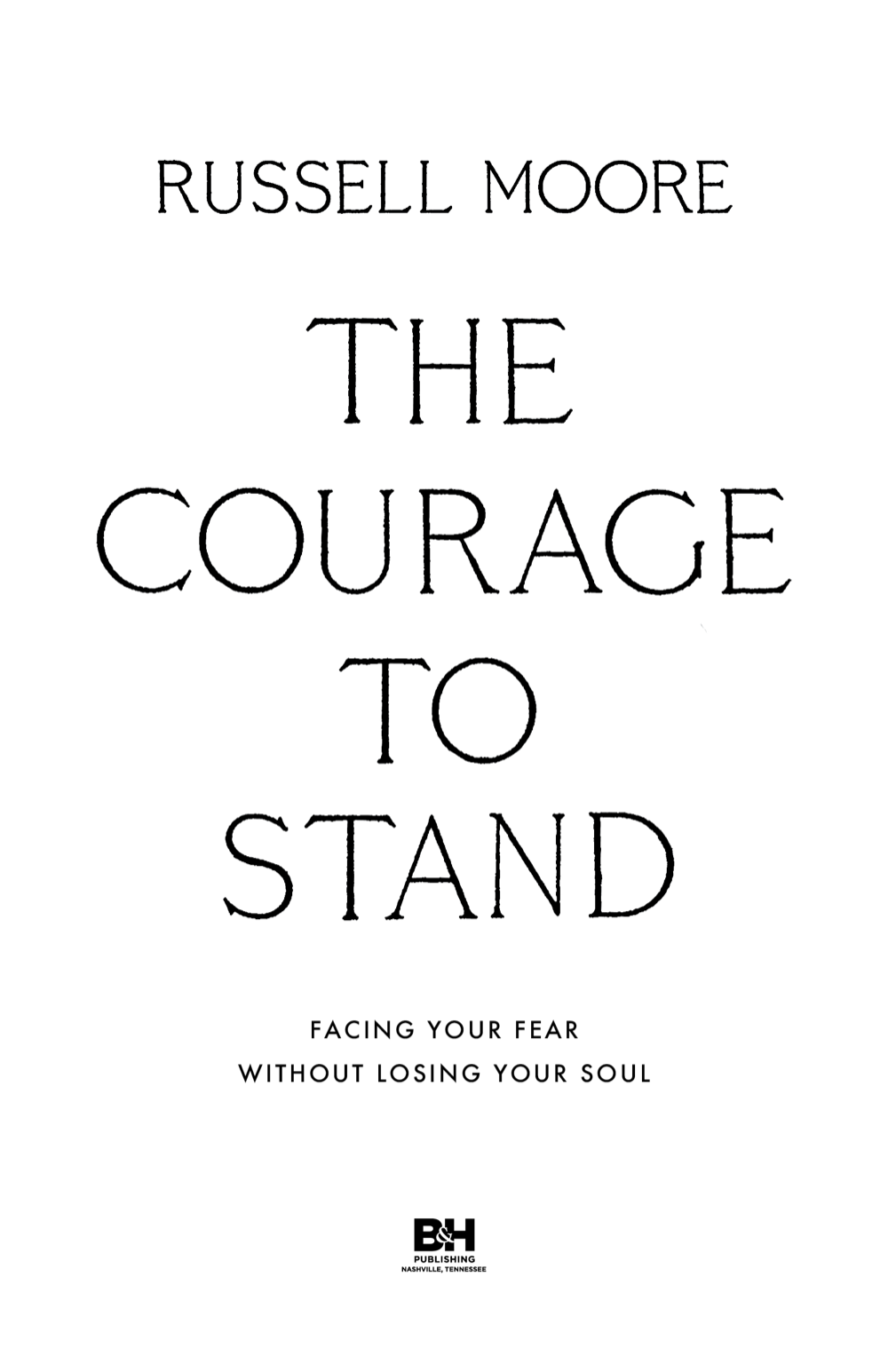

Copyright 2020 by Russell Moore

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

978-1-5359-9853-6

Published by B&H Publishing Group

Nashville, Tennessee

Dewey Decimal Classification: 179

Subject Heading: COURAGE / CHRISTIAN LIFE / FEAR

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture is taken from the English Standard Version. ESV Text Edition: 2016. Copyright 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

Also used: New International Version ( niv ), copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica.

Also used: King James Version ( kjv ), public domain.

Cover design and illustration by Stephen Crotts.

It is the Publishers goal to minimize disruption caused by technical errors or invalid websites. While all links are active at the time of publication, because of the dynamic nature of the internet, some web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed and may no longer be valid. B&H Publishing Group bears no responsibility for the continuity or content of the external site, nor for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 24 23 22 21 20

To my parents,

Gary and Renee Moore,

Thank you.

Introduction

W henever I lose my way in life, there are two maps on the wall that can help me navigate my way back home. That happens more often than I would like to admit, but whenever it does, the maps are always there. One of those maps is of the state of Mississippi, with a dot hovering over the coastline there where I grew up. The other map is of a land called Narnia. Those maps help remind me who I am, but, more importantly they remind me what Im not, what I almost was.

And what I almost was is a teenage suicide.

That last sentence there I have written, and unwritten, at least a dozen times. Im scared to disclose it, because Ive never discussed it before, even with close friends. But thats what this book is about: finding a way in the midst of fear, to somehow, having done all else, to stand.

Those maps are just scraps of paper, but, to me, they are almost portals to alternative realities, and in one of those realities I am dead. In the other reality, I found my way here, through a wardrobe in a spare room somewhere in England.

Many people, I know, spend a lifetime traumatized and scarred by their childhood religious community. Ive heard the stories so often that it startles me how similar the narratives can be, no matter how different the religious backgrounds. Most of the skeptical unbelievers I meet on college campuses or elsewhere are civil and sincere, but when I encounter someone who is hostile or ridiculing of me because of my faith, Ive learned to see that, in almost every case, theres a great deal of pain underneath, pain that comes often from some cruel or disappointing religion. That, though, is not my story. As a matter of fact, my home church growing up was a respite for me, the safest place I could, or can, imagine. Our pastors were, for the most part, authentic and humble leaders, and, even now, I aspire on my best days to be like them. The men and women in that church were like that too. Flawed and fallen, as we all are, they modeled for this child a world in which the gospel really did seem to be good news. And when they sang, Im so glad Im a part of the family of God, I could tell they really meant it. And so did I. I dont wish to idealize that little congregation, but its hard not to do so when, the older I get, the more I am convinced that God really was at work in that place. I well up with gratitude whenever I smell anything that evokes one of those musty Sunday school rooms, or whenever I taste cinnamon gum, which one of the elderly ladies would hand me right before church. When I recite the creedal phrase I believe in the communion of saints, what first comes to mind is not an assembly of ancient church fathers or reformers or famous missionaries, but these peopletruck drivers and cafeteria workers and electricians, who showed me what it meant that Jesus loved me.

Moreover, our liturgical calendar was low-church, and rooted in Nashville rather than Rome or Canterbury, but the rhythms of that calendar ordered my life just as surely as for a medieval monk, with fall and spring revivals, summer youth camps, weekly Sunday schools and evangelism training and choir practices. And, of course, there was the Bible. Sometimes I feel that modern English is my second language, with King James my native tongue. I lived and breathed and found my being in that book, and I have the award ribbons to prove it. Hard to imagine anything like this now, but in that world Sword Drills were common, sort of like a spelling-bee except in which children compete to find Bible verses the fastest (sword because the Word of God is the sword of the Spirit and is sharper than any two-edged sword). More often than not, I won those duels, not because I was smarter or holier than my peers, but because I was transfixed with the stories of that book. That was true even in those parts of the Bible I found incomprehensible, such as, up until puberty, the Song of Solomon, and, up until now, the Revelation of John.

My church was not a place of trauma, but, nonetheless, trauma found me. Around the age of fifteen I found myself in a dark wood, a spiritual crisis that spun out into a nearly paralyzing depression. While my church didnt prompt this crisis, I couldnt turn to the church at that moment because I started to wonder if Jesus was the problem, not the solution. What prompted the crisis was the Christian world outside of my church, the American Christianity of the Bible Belt, which was easy to see because that sort of cultural religiosity was the ecosystem in which we lived. Much of it seemed increasingly to me to be buffoonish and even predatory. But, beyond all that, I started to fear that maybe Christianity was a means to an end. Again, I didnt question the authenticity of my church mothers and fathers, but I started to fear that maybe they were the exception rather than the rule to what it meant to be Christian. Though I never doubted their sincerity, I started to wonder if maybe they, along with me, were being duped.

Some of that had to do with the explosion at the time of prophecy conferences and end-times expos, in nearly every town and almost everywhere across the airwaves. People who would rarely even go to church, any church, would drive miles to hear an evangelist explain why the founding of the secular state of Israel meant that, almost guaranteed, the world would end by 1988. That was when I turned sixteen. That was supposed to be exciting to me, I knew, but I was an awkward adolescent virgin, wondering why, if I had to live firsthand through one of those incomprehensible books, it couldnt be the Song of Solomon instead of the Revelation of John.

The year 1988 came and went, of course, with my prophecy charts and my virginity both still firmly within my possession. But no one apologized or even explained why those predictions didnt happen. Likewise, the Soviet Union was supposed to be the Gog and Magog of Bible prophecy, setting off the cataclysmic Battle of Armageddon, we were told. Eventually, though, the flag would come down from the Kremlin, with no one to tell us why the world was never forced to kneel before Gog. The problem, for me, was not just the obvious failures of accuracy here, contrasted to the authority with which such predictions were made; it was that the biblical proofs of all this stuff seemed secondary to what sort of interest they would draw. The Bible verses used to support all of these provocative claims were peppered about so quickly, with no context, that one would have to be a Sword Drill champion even to find them all, much less to fact-check the claims. But a Sword Drill champion is what I was. And it started to seem that the point of all of this was something other than a careful reading of what the Bible said.