Gratefully, I dedicate this book

to Josie Stanton for your loving-kindness and valuable insights into Buddhism

and

to Harrison E. Salisbury for encouraging me to publish this work.

To Khunying Arun Kitiyakara and Khun Thawin Pongsamart for your concerned assistance in helping me in my search for an understanding of your way of life.

To the Buddhist communities of Wat Bovornives, Wat Sraket, and Wat Muang Mang especially to the patient and kind teaching monks.

Also to my friends, Elizabeth Sewell, William Bradley, Konrad Bekker and Sarah Bekker for your contributions in making this book a reality.

And to Buzz for your inspiring and loving support of my intellectual pursuits.

CONTENTS

by Harrison E. Salisbury

T HERE is in the West today a growing sense of alienation, of the failure of Western philosophy, Western psychology and Western religion to cope with the ever-more complex problems which the post-industrial age has brought to mankind.

The earlier conviction of certainty, of absolute faith, of the superiority of Western logic and Western thinking to resolve any challenges which Man might encounter, has gradually been eroded by the increasing failure of science to meet human needs.

The iron positivism of a Cromwell, the sublime certainty of the 18-century Church of Rome and 19-century Protestantism, have vanished, and once again Man is left to struggle with the ever-widening gap between his perception of reality and the instruments which he can employ to help him comprehend that reality and his place within it.

No longer can there be doubt that the spreading sense of the futility and inadequacy of Western concepts underlies the explosion of interest in Eastern religion and philosophy which is now sweeping the West.

Of course, it is true that this explosion has long been in the building. Even before World War I active exploration of Eastern knowledge and culture was well advanced particularly the knowledge and culture of India. So far as China was concerned there was scholarly (but hardly popular) interest in Confucianism. Japan was virtually untouched. So was South-east Asia, although the mysteries of Tibet and Mongolia had long attracted the curious and the esoteric.

However, it is fair to say that popular interest in Buddhism, and specifically in its central concept of meditation, is of extremely recent origin, almost entirely a post-World War II phenomenon. This is especially true for Americans whose attention first began to be directed toward Zen Buddhism, for example, only during the 1960s, coincident with the sudden appearance of the hippie movement.

Interest in meditation, once stimulated, seems to have grown with remarkable speed in all Western countries. There are doubtless many reasons for this but the overriding one, or so it would seem to me, is the widening gap between Man and his technological milieu. The typical habitant of Technologia is highly educated, highly motivated, anti-religious or a-religious in the formal sense, sophisticated, urban and very often Freudian or Jungian. And the resident of Technologia, she or he, very often is unable to put it all together. Life seems to possess no meaning. Existence contains neither ease nor satisfaction. The very act of existence seems insolently oppressive. Who am I (the identity crisis)? Where are we going (concern over civilizations ability to survive)? Why (the meaning of existence)? These are the questions heard again and again in New York, London, Paris, Moscow, Rome and Los Angeles. There are no answers.

It is the existence of this phantasmagoria of disconnection and disassociation which has directed so many to the East in search of an answer. Gurus become a Pop phenomenon. Zen comes to Broadway and Piccadilly. Dick Cavett brings Transcendental Meditation to national television, and suddenly the initials TM becomes as familiar as ABC.

In the huffing, puffing and hullabaloo no one notices that behind the talk and the television there is little content. Who actually knows or understands meditation as it is taught in the Buddhist East?

This, perhaps, is the central question, and it is that admirable service which Jane Hamilton-Merritt renders she knows. She knows because she has had the endurance (and it does take endurance), the imagination (which so few possess), and the sympathetic understanding (the key to it all) to learn. To learn not merely from studying the Buddhist texts and the teachings of the Masters, but by personal experience. Alone, or almost alone among Westerners, she has gone to a teaching wat in northern Thailand, has sat at the feet of a genuine master, has lived the lonely, harsh and dangerous life of an acolyte in the cell. She has returned to describe her experience in tones so delicate, terms so precise and with such a bubbling sense of personal involvement that we find ourselves racing through her pages and ultimately, like Jane Hamilton-Merritt, actually capturing a sense of meditating.

We learn that meditation is not easy. It should not be undertaken lightly. It probably is not the thing for all, although all could benefit from it. It takes patience and fortitude. You do not simply sit in the half-lotus position, fix your eyes on a distant spot and begin to meditate. It is hard and it must be learned and practised.

But its rewards are great. Not easily described but palpable and tangible. It can bring the meditator understanding, deep insight, and relaxation, a new awareness of self, a revelation of depths in psyche and in the world such as cannot be imagined.

Meditation is central to Buddhism. It brings richness to life unlike that of any other human process. It may not afford the only avenue by which Man and Technologia can become reconciled, but it possesses potentials no other technique can match. Meditation may be the only thing which will make the post-industrial world habitable. Jane Hamilton-Merritts experience will suggest to almost everyone why this can be true.

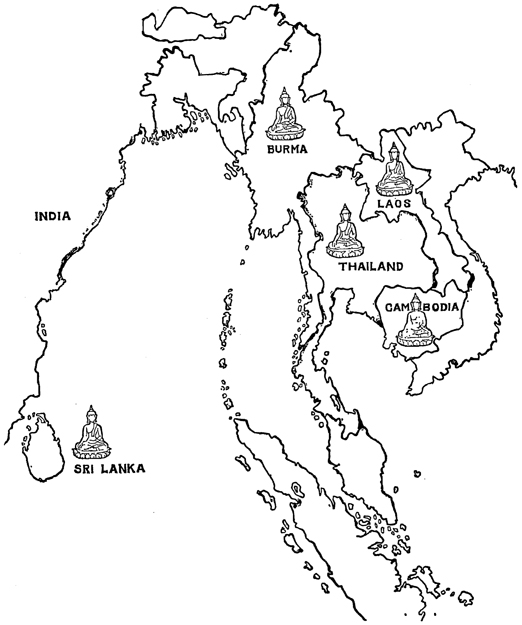

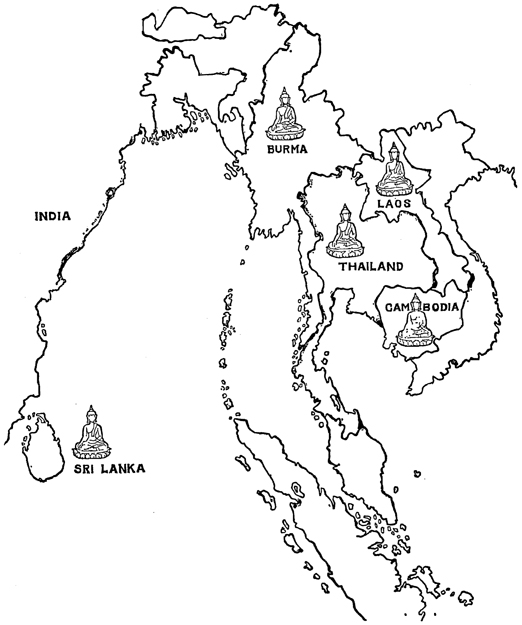

T HE road from the cornfields of Indiana where I grew up to the Buddhist temples of Southeast Asia has been long, arduous, frustrating, and often painful. This road, stretching half way around the world, carried me to Japan to attend graduate school; to Cambodia, Burma, Thailand and Laos to live among their peoples; to South Vietnams southern deltas, to its De-militarized Zone at the 17th parallel to photograph and write about the war and all the peoples involved; to remote mountainous villages inhabited by opium-growing ethnic minorities with whom I lived and about whom I wrote; and eventually into Buddhist temples where I became a part of the religious community and learned of Theravada Buddhism and meditation.

The inspiration for this long journey, which spanned over a decade, began when I, as a child of ten, encountered Pearl Bucks books on China. I knew that one day, I, too, would travel to those lands to see the peoples and cultures for myself. When I grew up, Americans were forbidden to travel to China, but politics did not diminish my desire to know more about Asian peoples and their cultures. Little did I know that one day I would be sitting before a Buddhist monk in a small temple in Northern Thailand struggling to learn Buddhist meditation.

As I learned more and more about the Southeast Asian cultures, particularly those of Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, I came to realize that the role of Buddhism in their lives and psyche was paramount to the understanding of these peoples. I became more and more interested in this Southeast Asian form of Buddhism known as Theravada Buddhism and tried to involve myself in it. But this was difficult. I could go to the temples, or wats and observe, which I often did. I could attend ceremonies with my Asian friends and I could talk with religious people, but I never became a part of the community. I was never on the inside; I remained the farang, the foreigner.

Next page