Prologue

When I was young, I thought that fearlessness and an easy way with love would see me to the other side of anything. Madness taught me otherwise. In the wake of my first insanity I assumed less and doubted more. My mind was suspect; there was no arguing with the new reality. I had to learn to live with a brain that demanded more coddling than I would have liked and, because of this, I avoided perturbance as best I could. Needwise, I avoided love.

I kept my mind on a short lead and my heart yet closer in; had I cared enough to look I doubt I would have recognized either of them. Before mania whipped through my brain I had been curious always to go to the far field, beyond what lay nearest by. After, I drew back from life and watered down my dreams. I retaught myself to think and to negotiate the world, and as the world measures things, I did well enough.

I was content in my life and found purpose in academic and clinical work. I wrote and taught, saw patients, and kept my struggles with manic-depressive illness to myself. I worked hard, driven to understand the illness from which I suffered. I settled in, I settled down, I settled. In a slow and fitful way, predictability insinuated itself into my life, and with it came a certain peace I was not aware had been missing. Grateful for this, and because I had no reason to know otherwise, I assumed that peace was provisional upon an absence of passion or anything that could forcibly disturb my senses. I avoided love.

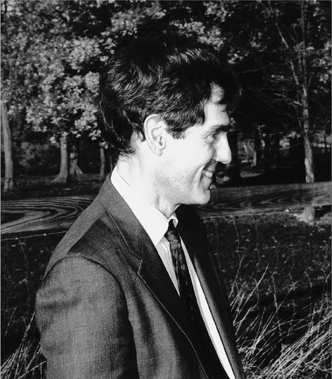

This lasted for a while, although not perhaps as long as it seemed. Then I met a man who upended my cautious stance toward life. He did not believe, as I had for so long, that to control my mind I must first control my heart. He loved the woman he imagined I must have been before bowing to fear. He prodded my resistance with grace and undermined my wariness with laughter. He could say the unthinkable because he instinctively knew that his dry wit and gentle ways would win me over. They did. He was deft with my shifting moods and did not abuse our passion. He liked my fearlessness, and he brought it back as a gift to me. Far from finding the intensity of my nature disturbing, he gravitated toward it. He induced me to risk much by assuming a portion of the risk himself, and he persuaded me to write from my heart. He loved in me what I had forgotten was there.

We had nearly twenty years together. He was my husband, colleague, and friend; when he became ill and we knew he would die, he became my mentor in how to die with the grace by which he lived. What he could not teach meno one couldwas how to contend with the grief of losing him.

It has been said that grief is a kind of madness. I disagree. There is a sanity to grief, in its just proportion of emotion to cause, that madness does not have. Grief, given to all, is a generative and human thing. It provides a path, albeit a broken one, by which those who grieve can find their way. Still, it is griefs fugitive nature that one does not know at the start that such a path exists. I knew madness well, but I understood little of grief, and I was not always certain which was grief and which was madness. Grief, as it transpires, has its own territory.

PART ONE

A SSURED BY L OVE

How like you to be kind,

Seeking to reassure.

And, yes, how like my mind

To make itself secure.

THOM GUNN

T HE P LEASURE OF H IS C OMPANY

Death forces cold decisions. Five years ago, as I waited in my husbands hospital room the night before he died, I was numb with fear. The doctor in the intensive care unit had been blunt. Mrs. Wyatt, he said, we need to talk about what your husband would have wanted done. I reached out instinctively to my husband, the person who had made bearable so many painful things over the years, and for a short while was reassured by the warmth of his hand. The reassurance was illusory, however, as any reassurance must be when it comes from the dying. The doctor and I talked about what had to be done.

My husband, nothing if not a practical man, had detailed years earlier the final medical decisions he wished to be made on his behalf, sparing me now some measure of pain and uncertainty. Indeed, he had laid out with such precision the circumstances under which he wished to have life support measures removed that the attending physician cited his directives to the medical students and residents as a model of how such things should be drawn up. Dr. Wyatt, he told them, was a scientist as well as a doctor, and it showed in the precision of his orders.

Richard, I told myself, was also a teacher, and he would have been pleased to be teaching in death as he had in life. He would have laughed and said that, all things considered, he would have preferred to be alive and to have left this particular kind of teaching to someone else. The warmth of his hand may have been illusory, but the recollection of his wit was not. For a moment I felt the solace and pleasure of his company.

The decision to sign the papers to end Richards life was difficult but peculiarly straightforward. His medical condition and the specifics of his advance directives made signing, however haunting, inevitable. It was a final and necessary act. More wrenching was the decision of where to spend the last night we would have together. There should have been no question at all. Every human instinct, every impulse of love and friendship, told me I should be with him at the end. It did not matter that he was unconscious and would not be conscious again. The desire to hold and console, to accompany, is ancient for cause: it is human; it is who we are. Left to my own ways, before Richard became a part of how I faced the world and my disquietude, I would have been by him all night, not willing or able to sleep. I could not have imagined otherwise. To spend our final night apart seemed monstrous.