Contents

ALSO BY KAY REDFIELD JAMISON

Nothing Was the Same

Exuberance:

The Passion for Life

Night Falls Fast:

Understanding Suicide

An Unquiet Mind:

A Memoir of Moods and Madness

Touched with Fire:

Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament

TEXTBOOKS

Abnormal Psychology

(with Michael Goldstein and Bruce Baker)

Manic-Depressive Illness:

Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression

(with Frederick Goodwin)

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2017 by Kay Redfield Jamison

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York,

and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada,

a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Owing to limitations of space, permissions to reprint previously published material appear beginning on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jamison, Kay R., author. | Traill, Thomas A., author.

Title: Robert Lowell, setting the river on fire : a study of genius, mania, and character / Kay Redfield Jamison.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028281 | ISBN 9780307700278 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101947968 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Lowell, Robert, 19171977Mental health. | Manic-depressive personsUnited StatesBiography. | Poets, American20th centuryBiography. | Genius and mental illness. | Creative ability. | BISAC : BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | PSYCHOLOGY / Psychopathology / Depression. | PSYCHOLOGY / Creative Ability.

Classification: LCC RC 537. J 356 2017 | DDC 616.89/50092 B dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028281

ISBN9780307700278

Ebook ISBN9781101947968

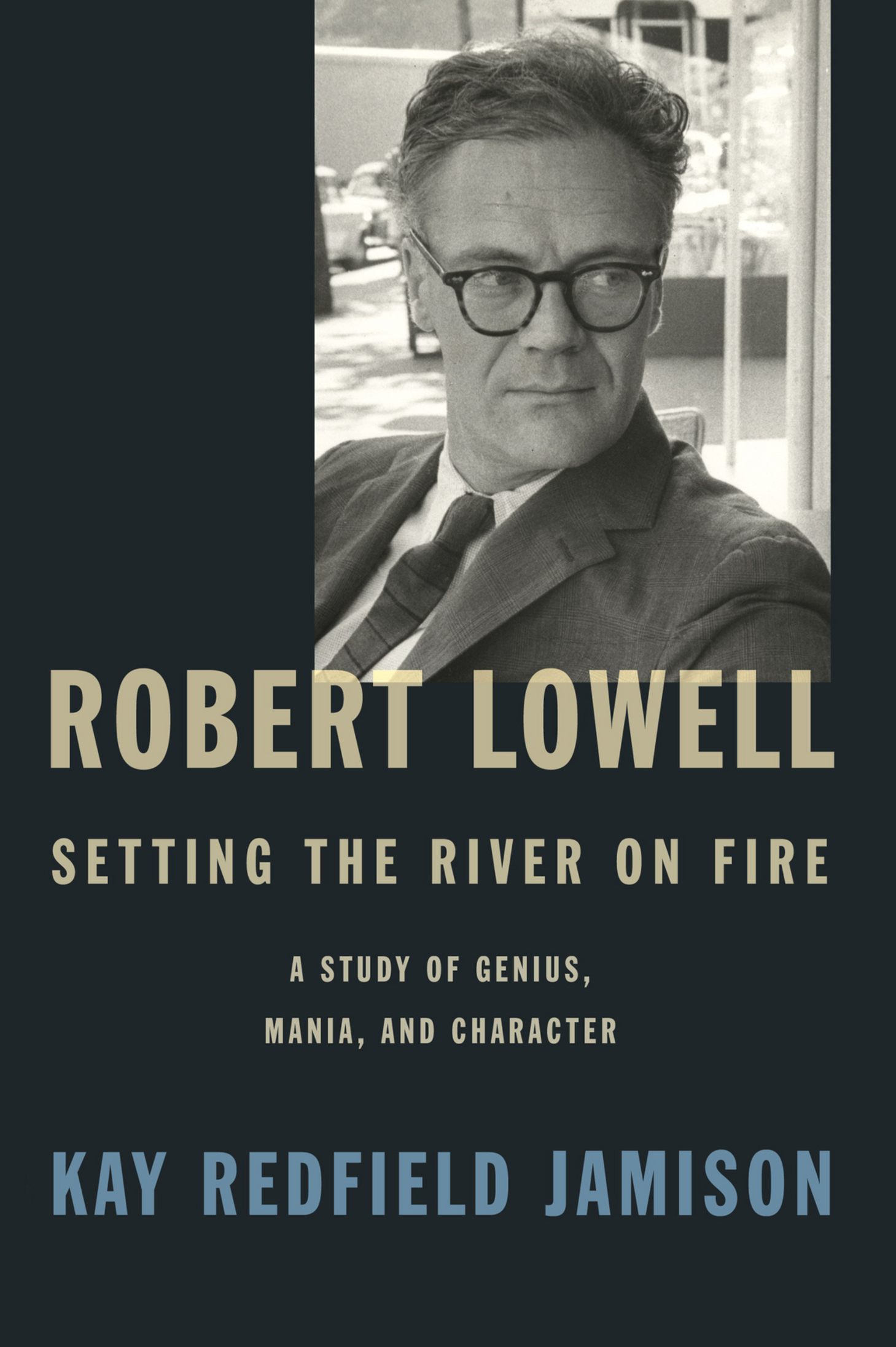

Cover photograph of Robert Lowell by Gisle Freund/IMEC/Fonds MCC

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

First Edition

v4.1

a

For my husband,

Tom Traill

For a week my heart has pointed elsewhere:

it brings us here tonight, and ties our hands

if we leaned forward, and should dip a finger

into this rivers momentary black flow,

infinite small stars would break like fish.

From The Charles River

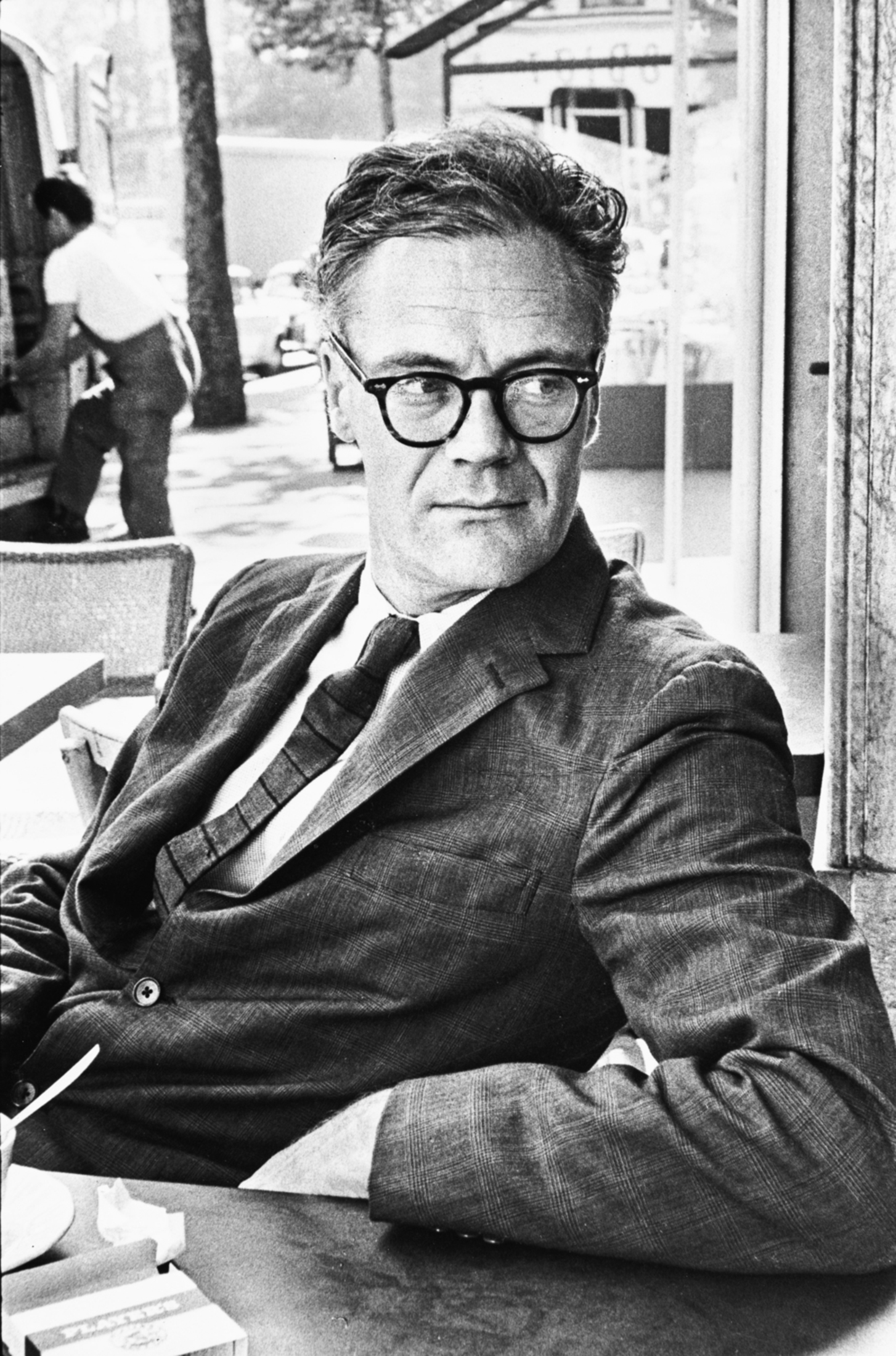

Robert Lowell in Paris, 1963

Reading Myself

Like thousands, I took just pride and more than just,

struck matches that brought my blood to a boil;

I memorized the tricks to set the river on fire

somehow never wrote something to go back to.

Can I suppose I am finished with wax flowers

and have earned my grass on the minor slopes of Parnassus.

No honeycomb is built without a bee

adding circle to circle, cell to cell,

the wax and honey of a mausoleum

this round dome proves its maker is alive;

the corpse of the insect lives embalmed in honey,

prays that its perishable work live long

enough for the sweet-tooth bear to desecrate

this open bookmy open coffin.

Robert Lowell

Contents

Prologue

Old Cambridge, Massachusetts

March 19, 1845

No one knew what she was thinking. It was a short carriage ride; perhaps she was not thinking much at all. In regard to her mind, her husband had said, I hardly know what to say. No one did. Had she looked from her carriage window the tracks in the snow might have triggered a memory from childhood, helped to ward off the present. More likely, that kind of innocence was past retrieving. The Boston paper had said that todays snow was a March sugar snow, one that would speed the flow of maple sap in the New England sugar orchards. As a child she might have found pleasure in such an image; she had been known for her lively mind. Now she was impenetrable. In her sons words, only as much of her remained as the hum outliving the hushed bell.

The carriage took her from Old Cambridge to Somerville, a neighboring town on the banks of the Mystic River. It took her away from her husband, children, and their home with its great elms and long view of the Charles River. The house, built for a colonial loyalist, had in its time been a field hospital for Washingtons troops and then home to a vice president of the United States. Later it would become the official residence for the presidents of Harvard. But for the passenger it was the house in which she had lived with her family for nearly thirty years and where her youngest child had been born. She was about to exchange one grand house for yet a grander one, one view of the Charles River for another. It was not an exchange anyone would willingly make.

Had the passenger cared, and had she kept an eye open for such things, she would have noticed that a street in the town of Somerville was named for her husbands family; so too was one of its railroad lines. Beyond the town limits an entire city bore his name. Her husbands name could be found in many places, it seemed, but it was of little help. It could not make right what was wrong in her head. And it was what was wrong in her head that brought her to Somerville.

The carriage drove up Cobble Hill and stopped at the large mansion built in the eighteenth century for a Boston merchant. The two-hundred-acre estate of gardens and fishponds, fruit orchards, and a rose-covered summerhouse had been described by a visitor to Boston in 1792 as infinitely the most elegant dwelling house ever yet built in New England. When the original owner died, the wealthy of Boston, the treasurers of Gods bounty, had purchased the residence and a portion of the grounds in order to provide for the class of sufferers who peculiarly claim all that benevolence can bestowthe insane. This most elegant dwelling house was now the McLean Asylum for the Insane and it was here that Harriet Brackett Spence Lowell was committed on March 19, 1845.

She arrived at the asylum in a very irritable state. She would not permit the attendant to help her from her carriage nor would she allow anyone to carry her cloak. She would not converse with the other boarders and was all the while scolding the staff. Her name, entered into the asylums admission book, joined those of other old New England familiesbrokers and bankers, university presidents, writers, legislators, and merchantswhose ancestors had sailed on the early ships from England. Others, not so often with Mayflower namesthe blacksmiths, rope makers, sailmakers, farmers, and whalers who lived and worked in Boston or other towns in New Englandwere also in the ledger. Insanity then, as now, cut across class and circumstance.