Religion in the South

John B. Boles, Series Editor

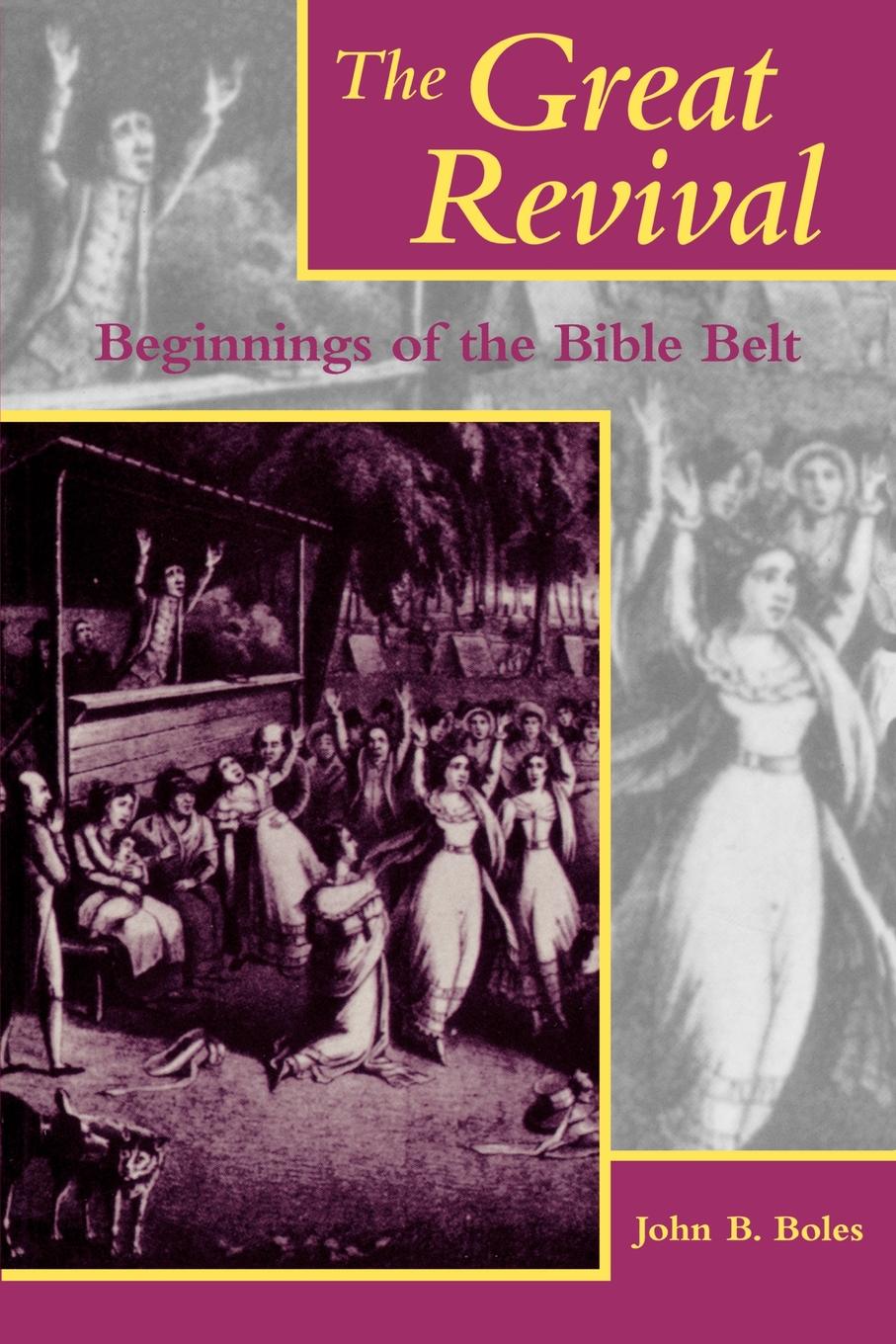

The Great Revival

Beginnings of the Bible Belt

JOHN B. BOLES

Copyright 1972 by The University Press of Kentucky

Originally published as The Great Revival, 1787-1805:

The Origins of the Southern Evangelical Mind.

Preface to the paperback edition

Copyright 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from

the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-0862-9 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

for Nancy

Contents

Preface

to the

Paperback Edition

Thirty years ago I entered graduate school at the University of Virginia, and that first semester I wrote a seminar paper on James McGready and the Great Revival. The previous spring, an undergraduate anthropology course at Rice University entitled Primitive Religion had introduced me to the subject of southern revivals with colorful descriptions of camp meetings. I was fascinated with the accounts of extravagant emotional excess, complete with people reportedly jerking spasmodically, barking, running around on all fours, and treeing the devil. So when the graduate dean told us graduate students in our orientation meeting to choose a dissertation topic quickly, I, perhaps naively, almost instantly decided to study this apparently outrageous revival movement.

But as soon as I began reading the original sources, it seemed evident that more than raw emotion was at work on Frederick Jackson Turners western frontier. Even these Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian preachers had a set of ideas and expectations about religion. To my initial surprise, there was an ideational world that lay behind and helped explain the outbreak of religious revivalism that began in Kentucky and soon swept back across much of the South. This, I became convinced, was in truth the Souths First Great Awakening. The resulting research led to my 1969 dissertation and this book, originally published in 1972.

Returning to the subject after more than two decades, I am struck both by how little of the original text I would like to change and by how much the field of scholarship has evolved. If I were approaching the topic today, I would pay far closer attention to the role of gender; rather than say how people or listeners responded, I would suggest the often different responses and roles of men and women. I would now make more of the analytical concept of revitalization movements, which I mentioned in 1972 only in the then-current fashion of submerging, rather than highlighting, theory. I would also clarify what I meant by arguing that southern evangelical religion was individualistic in focus; I of course did not mean that evangelicals did not create and value local religious communities, their congregations. I referred to the relative absence of a social dimension to their religious concern, the kind of emphasis among many northern evangelicals that led to a focus on societal as well as individual flaws. Hence I reached my basic conclusion that southern evangelicalism has been on the whole a conservative force in southern life.

I was completing the dissertation on which this book is based in the very midst of the debate among many scholars, particularly black scholars, about the appropriateness of whites attempting to write black history. The years 1968 and 1969 witnessed fierce debates about such books as William Styrons The Confessions of Nat Turner, debates that involved several of my graduate professors. More than twelve hundred people crowded into a ballroom of the Jung Hotel during the 1968 meeting of the Southern Historical Association in New Orleans to hear a spirited exchange on the topic in which individuals in the audience berated participant Styron for his treatment of Nat Turner. Because I was a southern white student educated in southern universities, my Virginia professors as well as several elsewhere, even from as far away as Berkeley, suggested that the times were not propitious for my essaying any conclusions about the nature of white-black religious relations at the time of the Great Revival.

Given the tenor of the times, I think they were correct to urge caution, so the resulting book explicitly said it would emphasize white evangelicals. But, ironically, the book came out in 1972, the year in which books by John Blassingame and George Rawick helped revolutionize the study of slavery. Soon came a series of great books by scholars such as Eugene Genovese, Herbert Gutman, Peter Wood, Lawrence Levine, Edmund Morgan, and others. Tensions eased, and the history of the African American experience became one of the glories of academic scholarship. By 1976, emboldened by the pioneering work of others, I wrote a small book entitled Religion in Antebellum Kentucky that had a chapter on black Christianity and another on the response of the so-called white churches to the slavery issue. I subsequently explored the religion of slaves still more in Black Southerners, 16191869 (1983), in Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 17401870 (1988), and in The Irony of Southern Religion (1994). If I were today to rewrite The Great Revival, I would include the involvement of blacks in the revival movement and emphasize the revivals role in evangelizing the southern slave community. Christianity and the church were essential aspects of the black historical experience in the antebellum South, and I should have told more of the story in 1972.

In retrospect, I marvel at how far the field of southern religious history has come since The Great Revival was published. It is difficult to imagine the field without the pioneering works of Samuel S. Hill, Rhys Isaac, Donald G. Mathews, David E. Harrell, Jan E. Lewis, Albert J. Raboteau, C.C. Goen, Mitchel Snay, James O. Farmer, Jean E. Friedman, Randy J. Sparks, Kenneth K. Bailey, Dickson D. Bruce Jr., E. Brooks Holifield, David T. Bailey, Paul K. Conkin, Leigh Eric Schmidt, Anne C. Loveland, John W. Kuykendall, Mechal Sobel, Sylvia R. Frey, Robert M. Calhoon, Charles R. Wilson, Wayne Flynt, and many others. I flatter myself by believing that in some incremental way my first book helped create the field. Admittedly, it is somewhat humbling, having learned so much from these and other historians, to look back at my youthful effort. But I believe the historiographical context in which it was written is best served by reprinting the volume as it originally appeared. I appreciate the opportunity of making it available to a new generation of readers.