INTRODUCTION

Telling Stories after the Storm

The first interview for this book was conducted in the spring of 2018, just seven months after Hurricane Mara decimated Puerto Rico. Zaira Arvelo Alicea and I met at an outdoor caf on the plaza of Rincn, a town on the west coast of the main island. She had been staying at a tiny Airbnb since the hurricane destroyed her home in the nearby town of Aguadilla and was happy to have any excuse to escape for a little while and sit in the sunshine. We were worried about the noise on the plaza as supply trucks frequently rumbled past, people walked by loudly discussing the hurricane, and the reverberations of tools being used to rebuild nearby homes and shops echoed through the air. Eventually, though, we agreed that there had been too much silence after Mara, so we let the recording of our discussion capture the background sounds of the activity all around us. The commotion underscored the fact that weand our communitieswere still alive.

Although it was the first time we met, we talked for hours that day, eating big, sloppy burgers with piles of crispy fries as if everything were normal, even finding small reasons to laugh together. As the conversation went on, though, I think that we were both grateful to have the framework of an interview to fall back on. It gave us a kind of permission to speak, to let go of some of what we were holding on to, even though it was hard for Zaira to talk about what had happened to her and difficult for me to listen to her story.

Zaira and her husband, Juan Carlos, had survived the hurricane by floating for sixteen hours on a patched air mattress. They were eventually rescued and brought to a small apartment where they stayed with twenty-two other evacuees for two nights before walking miles from their ruined home in Aguadilla to a family members house in Aguada. As Zaira was recounting their slow trek toward family, describing cars that had been caught up in a storm surge of ocean water and balanced upside down along the highway, she paused to ask, How do you describe the smell of decaying bodies? Our conversation for the day ended there as I turned off the recorder and reached for Zairas hand across the table. We held onto each other as a warm afternoon rain started to fall all around the caf umbrella that sheltered us.

Zairas narrative opens this collection, which is fitting for many reasons, perhaps the most important being that this interview significantly shaped the project while it was still in its infancy. We ultimately decided not to include the details of Zairas long walk down Highway PR-2 out of respect for the dead who were unknown to us and the grief that their families must feel in knowing that their loved ones laid on the roadside unattended for days after the hurricane. Hurricane Mara wasand isa site of trauma for all who have survived; that trauma entailed not only the violent storm that battered the archipelago for over thirty hours, but also the long months, now years, of inadequate relief and aid from governmental systems that exist to help those in crisis.

Our deep sense of respect for our narrators and their experiences has cultivated an obligation to recognize these survivors not as victims, but as heroes. This book is populated by stories of people who meet tragedy and loss with strength and hope. As Zaira and Juan Carlos worked to find resources for themselves, they simultaneously returned to their flooded community to help others fill out and file necessary FEMA paperwork and liaise with government officials. Even as they grappled with the loss of every one of their possessions, they turned their efforts toward aiding those around them. This is the ethos that infused the nascent beginnings of our project, one that works to underscore the widespread injustice of insufficient governmental disaster response while highlighting the fortitude of the individuals who survived Hurricane Mara and its aftermaths in Puerto Rico.

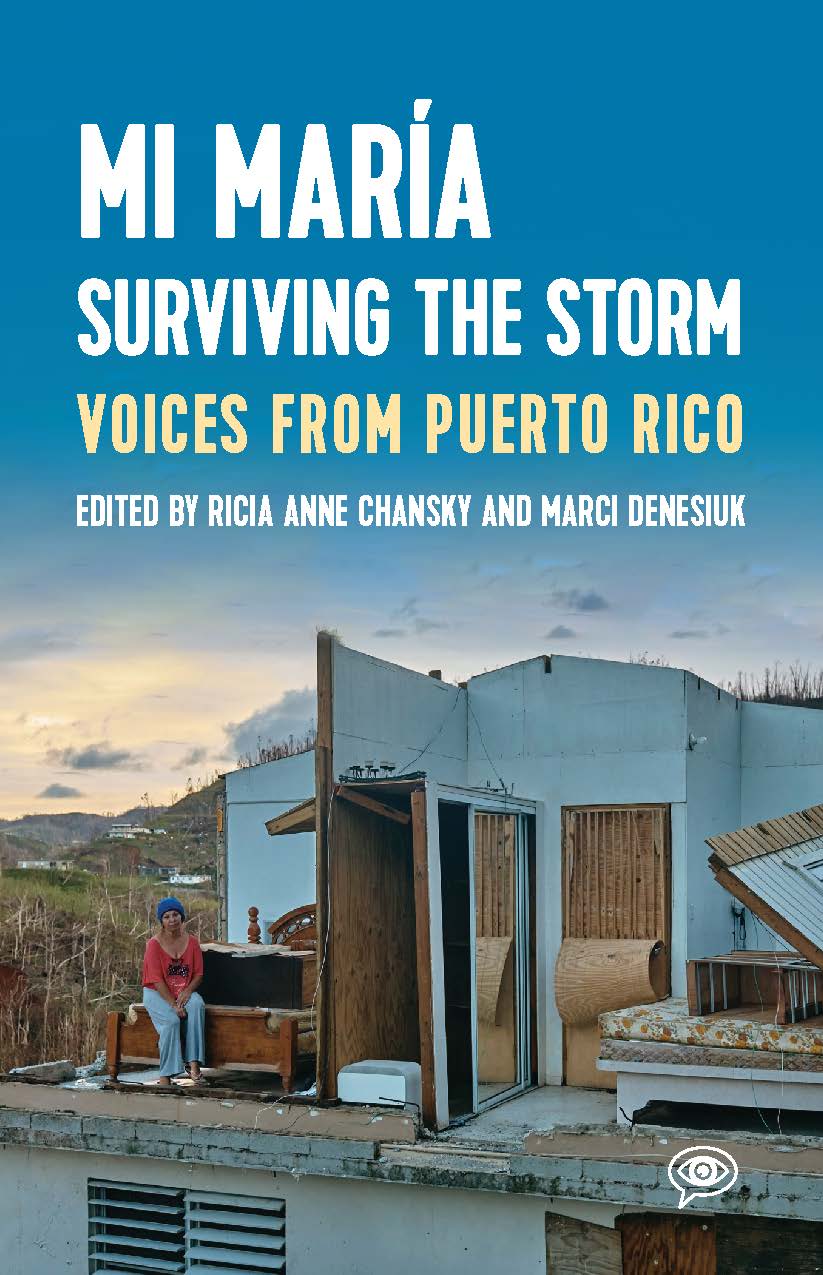

Even though Zairas was the first interview formally conducted for this book, the seeds of this project were planted months earlier in classrooms at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagez, where the editors of this volume teach in the English department. Hurricane Mara made landfall in the Puerto Rican archipelago on September 20, 2017, leaving no part of Puerto Rico unscathed. The hurricane triggered floods and mudslides, washed out roads, destroyed tens of thousands of homes, farms, and businesses, caused the largest blackout in US history (the second largest in the world), knocked out communications, led to widespread shortages in food, drinking water, and gasoline, and was ultimately responsible for thousands of deaths. When classes at the university resumed just over a month later, we returned to campus knowing that it was one of the only places on the west coast of Puerto Rico that had somewhat stable electricity and running water. The university became a haven for our students and our community, but we learned quickly that many students who had restarted their semesters were in precarious positions because of what they had lost in the storm.

U

Students wrote about the doors and windows of their family homes bursting open, watching helplessly as wind and rain destroyed their possessions. One student, Gabriel, wrote about how he and his grandmother held onto each other for hoursrocking back and forth and weeping togetheras the storm peeled off their roof, and their belongings whirled around them. There were stories about rivers overflowing their banks and storm surges of ocean water pouring through houses with three, nine, and even eleven feet of floodwaters and stinking mud filling homes. Others wrote about seeing the animals on their farms drowned and crops ruined, businesses destroyed, empty grocery stores and the search for drinking water, and towns that looked like postapocalyptic movie sets after the bomb went off. The words screaming and crying appeared over and over again.

Eventually, I came to Alejandras memoir, in which she described sitting helplessly on her porch as she watched her neighbors bury two of their family members in their backyard. The saddest thing, she wrote, was to see our neighbors digging graves in their backyards because relatives had passed away due to the lack of medical attention in Aguadilla, since the only hospital [there] had to be shut down and the electricity remained off. Her neighbors had been unable to receive their routine medical care and died because of it. Reading this narrative, catching a glimpse of what Alejandra carried with her every day, made me want to do more to alleviate that burden. This was the moment of commitment to a project that would gather stories of surviving Hurricane Mara in Puerto Rico, one that would assemble individual voices as part of a polyphonic narration of disaster, with the intent of making real change for us and others who have survived natural and human-made disasters.

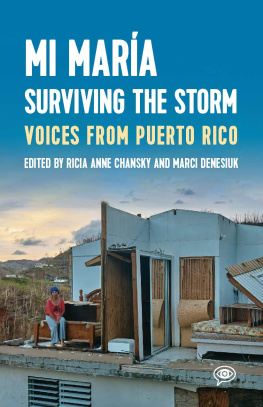

In August 2018, less than a year after the hurricane made landfall, we met this objective with the inception of the Mi Mara project, in collaboration with Voice of Witness. All of these students are survivors of Hurricane Maraeach with their own story to tellwho went into their home communities to collect unheard stories of the hurricane and its aftermaths. Many of the narratives collected in this volume began as oral histories recorded, transcribed, and translated by our students.

At the same time, Marci and I were also doing fieldwork, traveling through a Puerto Rico scarred by the hurricane and marred by insufficient relief efforts, in order to collect additional interviews. Our work brought us from a farm nestled in the peaks of the Cordillera Central mountain range in Adjuntas to a community arts center in the underserved neighborhood of La Perla in San Juan to a health clinic being rebuilt on the island of Culebra off the easternmost coast of the main island. We have edited these raw recordings into readable narratives, labor that has been exacting and, at times, daunting. Always, though, we have kept sight of the fact that this project is rooted in the work of our students and the communities that we participate in together.