Roger Crowley - Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453

Here you can read online Roger Crowley - Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: Faber and Faber, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber and Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

1453

ROGER CROWLEY

For Jan with love, wounded at the sea wall

in pursuit of the siege

Constantinople is a city larger than its renown proclaims. May God in his grace and generosity deign to make it the capital of Islam.

Hasan Ali Al-Harawi, twelfth-century Arab writer

I shall tell the story of the tremendous perils of Constantinople, which I observed at close quarters with my own eyes.

Leonard of Chios

Map of Constantinople from Liber insularium Archipelagi by Christoforo Boundelmonti c.1480

Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II c.1480, attributed to Shiblizade Ahmet

View of the nave of St Sophia

The imperial palace of Blachernae, from a nineteenth-century photograph

The Theodosian wall

The great chain strung across the Golden Horn, from a nineteenth-century photograph

Bronze siege gun in the courtyard of the Military Museum, Istanbul (authors photograph)

A Turkish Janissary, late-fifteenth-century, by Gentile Bellini

The siege of Constantinople from Le Voyage dOutremer by Bertrandon de la Broquire c.1455

Entry of Mehmet II into Constantinople, 29 May 1453 by Benjamin Constant, 1876

St Sophia transformed into a mosque, German School, sixteenth century

Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, c.1480 by Gentile Bellini

The Palace of the Despots, Mistra, Greece

All references to authors relate to their books listed in the bibliography, and can be found at the end of each chapter.

A red apple invites stones.

Turkish proverb

Early spring. A black kite swings on the Istanbul wind. It turns lazy circles round the Suleymaniye mosque as if tethered to the minarets. From here it can survey a city of fifteen million people, watching the passing of days and centuries through imperturbable eyes.

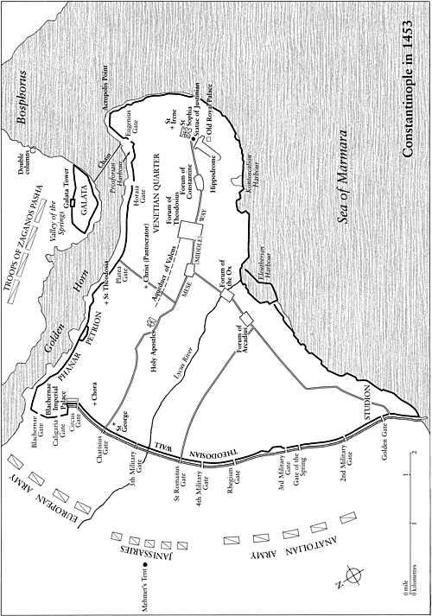

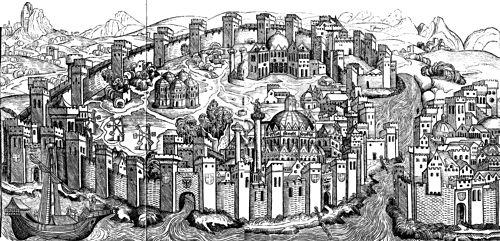

When some ancestor of this bird circled Constantinople on a cold day in March 1453, the layout of the city would have been familiar, though far less cluttered. The site is remarkable, a rough triangle upturned slightly at its eastern point like an aggressive rhinos horn and protected on two sides by sea. To the north lies the sheltered deep-water inlet of the Golden Horn; the south side is flanked by the Sea of Marmara that swells westward into the Mediterranean through the bottleneck of the Dardanelles. From the air one can pick out the steady, unbroken line of fortifications that guard these two seaward sides of the triangle and see how the sea currents rip past the tip of the rhino horn at seven knots: the citys defences are natural as well as man made.

But it is the base of the triangle that is most extraordinary. A complex, triple collar of walls, studded with closely spaced towers and flanked by a formidable ditch, it stretches from the Horn to the Marmara and seals the city from attack. This is the thousand-year-old land wall of Theodosius, the most formidable defence in the medieval world. To the Ottoman Turks of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it was a bone in the throat of Allah a psychological problem that taunted their ambitions and cramped their dreams of conquest. To Western Christendom it was the bulwark against Islam. It kept them secure from the Muslim world and made them complacent.

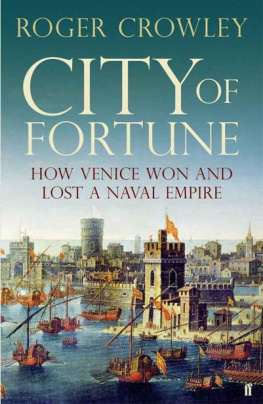

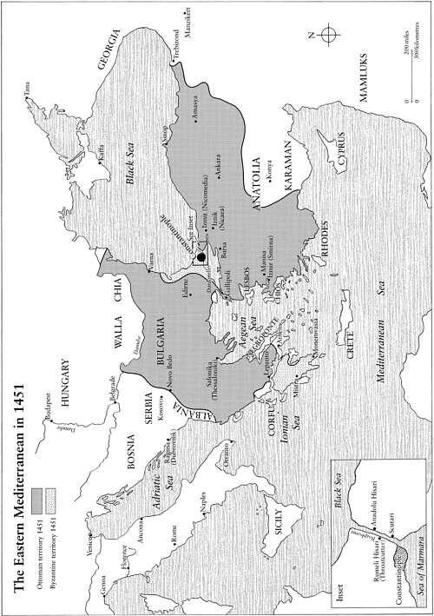

An imaginative view of the city in the fifteenth century. Galata is on the far right

Looking down on the scene in the spring of 1453 one would also be able to make out the fortified Genoese town of Galata, a tiny Italian city state on the far side of the Horn, and to see exactly where Europe ends. The Bosphorus divides the continents, cutting like a river through low wooded hills to the Black Sea. On the other side lies Asia Minor, Anatolia in Greek literally the East. The snow-capped peaks of Mount Olympus glitter in the thin light sixty miles away.

Looking back into Europe, the terrain stretches out in gentler, undulating folds towards the Ottoman city of Edirne, 140 miles west. And it is in this landscape that the all-seeing eye would pick out something significant. Down the rough tracks that link the two cities, huge columns of men are marching; white caps and red turbans advance in clustered masses; bows, javelins, matchlocks and shields catch the low sun; squadrons of outriding cavalry kick up the mud as they pass; chain mail ripples and chinks. Behind come the lengthy baggage trains of mules, horses and camels with all the paraphernalia of warfare and the personnel who supply it miners, cooks, gunsmiths, mullahs, carpenters and booty hunters. And further back something else still. Huge teams of oxen and hundreds of men are hauling guns with immense difficulty over the soft ground. The whole Ottoman army is on the move.

The wider the gaze, the more details of this operation unfold. Like the backdrop of a medieval painting, a fleet of oared ships can be seen moving with laborious sloth against the wind, from the direction of the Dardanelles. High-sided transports are setting sail from the Black Sea with cargoes of wood, grain and cannon balls. From Anatolia, bands of shepherds, holy men, camp followers and vagabonds are slipping down to the Bosphorus out of the plateau, obeying the Ottoman call to arms. This ragged pattern of men and equipment constitutes the co-ordinated movement of an army with a single objective: Constantinople, capital of what little remains in 1453 of the ancient empire of Byzantium.

The medieval peoples about to engage in this struggle were intensely superstitious. They believed in prophecy and looked for omens. Within Constantinople, the ancient monuments and statues were sources of magic. People saw there the future of the world encrypted in the narratives on Roman columns whose original stories had been lost. They read signs in the weather and found the spring of 1453 unsettling. It was unusually wet and cold. Banks of fog hung thickly over the Bosphorus in March. There were earth tremors and unseasonal snow. Within a city taut with expectation it was an ill omen, perhaps even a portent of the worlds end.

The approaching Ottomans also had their superstitions. The object of their offensive was known quite simply as the Red Apple, a symbol of world power. Its capture represented an ardent Islamic desire that stretched back 800 years, almost to the Prophet himself, and it was hedged about with legend, predictions and apocryphal sayings. In the imagination of the advancing army, the apple had a specific location within the city. Outside the mother church of St Sophia on a column 100 feet high stood a huge equestrian statue of the Emperor Justinian in bronze, a monument to the might of the early Byzantine Empire and a symbol of its role as a Christian bulwark against the East. According to the sixth century writer Procopius, it was astonishing.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453»

Look at similar books to Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.