PROLOGUE

The Prow of Europe

O N S EPTEMBER 20, 1414, the first giraffe ever seen in China was approaching the imperial palace in Beijing. A crowd of eager spectators craned their heads to catch a glimpse of this curiosity with the body of a deer and the tail of an ox, and a fleshy boneless horn, with luminous spots like a red cloud or a purple mist, according to the enraptured court calligrapher and poet Shen Du. The animal was apparently harmless: its hoofs do not tread on living creaturesits eyes rove incessantly. All are delighted with it. The giraffe was being led on a halter by its keeper, a Bengali; it was a present from the faraway sultan of Malindi, on the coast of East Africa.

The dainty animal, captured in a contemporary painting, was the exotic trophy of one of the strangest and most spectacular expeditions in maritime history. For thirty years at the start of the fifteenth century, the emperor of the recently established Ming dynasty, Yongle, dispatched a series of armadas across the western seas as a demonstration of Chinese power.

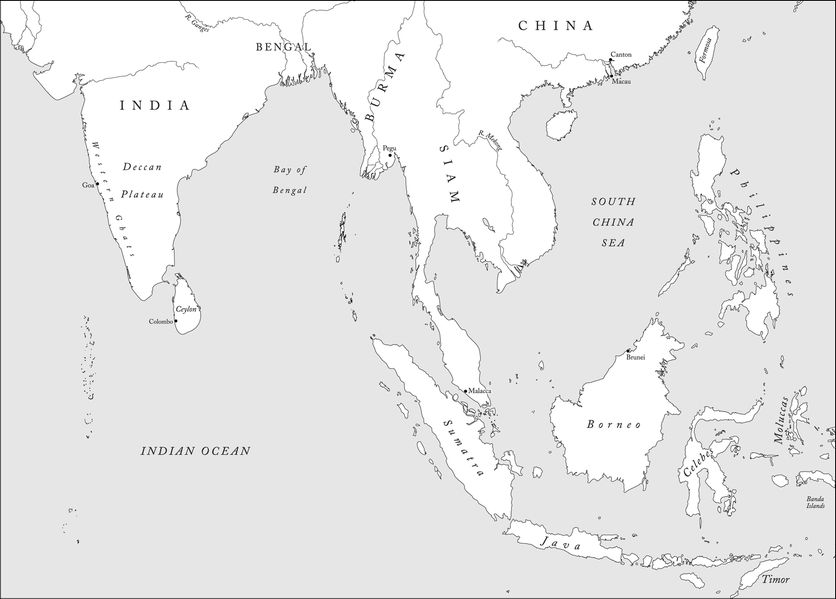

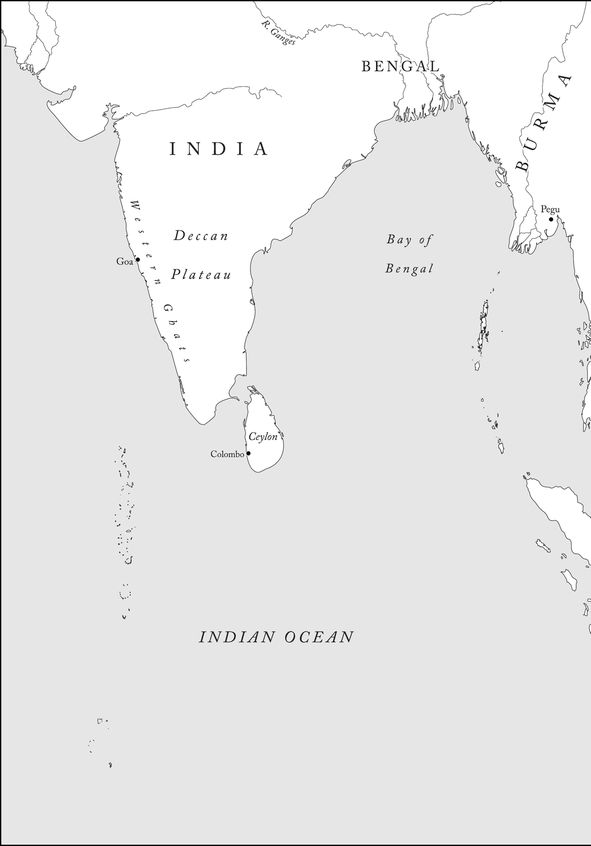

The fleets were vast. The first, in 1405, consisted of some 250 ships carrying twenty-eight thousand men. At its center were the treasure ships: multi-decked, nine-masted junks 440 feet long with innovative watertight buoyancy compartments and immense rudders 450 feet square. They were accompanied by a retinue of support vesselshorse transports, supply ships, troop carriers, warships, and water tankerswith which they communicated by a system of flags, lanterns, and drums. As well as navigators, sailors, soldiers, and ancillary workers, they took with them translators, to communicate with the barbarian peoples of the West, and chroniclers, to record the voyages. The fleets carried sufficient food for a yearthe Chinese did not wish to be beholden to anyoneand navigated straight across the heart of the Indian Ocean from Malaysia to Sri Lanka, with compasses and calibrated astronomical plates carved in ebony. The treasure ships were known as star rafts, powerful enough to voyage even to the Milky Way. Our sails, it was recorded, loftily unfurled like clouds, day and night continued their course, rapid like that of a star, traversing the savage waves. Their admiral was a Muslim named Zheng He, whose grandfather had made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and who gloried in the title of the Three-Jewel Eunuch.

These expeditionssix during the life of Yongle, and a seventh in 143133were epics of navigation. Each lasted between two and three years, and they ranged far and wide across the Indian Ocean from Borneo to Zanzibar. Although they had ample capacity to quell pirates and depose monarchs and also carried goods to trade, they were primarily neither military nor economic ventures but carefully choreographed displays of soft power. The voyages of the star rafts were nonviolent techniques for projecting the magnificence of China to the coastal states of India and East Africa. There was no attempt at military occupation, nor any hindrance to the areas free-trade system. By a kind of reverse logic, they had come to demonstrate that China wanted nothing, by giving rather than taking: to go to the [barbarians] countries, in the words of a contemporary inscription, and confer presents on them so as to transform them by displaying our power. Overawed ambassadors from the peripheral peoples of the Indian Ocean returned with the fleet to pay tribute to Yongleto acknowledge and admire China as the center of the world. The jewels, pearls, gold, ivory, and exotic animals they laid before the emperor were little more than a symbolic recognition of Chinese superiority. The countries beyond the horizon and at the end of the earth have all become subjects, it was recorded. The Chinese were referring to the world of the Indian Ocean, though they had a good idea what lay farther off. While Europe was pondering horizons beyond the Mediterranean, how the oceans were connected, and the possible shape of Africa, the Chinese seemed to know already. In the fourteenth century they had created a map showing the African continent as a sharp triangle, with a great lake at its heart and rivers flowing north.