IN THE SHADE OF

THE QURN

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful

Sayyid Qub

IN THE SHADE OF

THE QURN

F ill al-Qurn

VOLUME XVIII

SRAHS 78114 [JUZ AMMA]

Al-Naba Al-Ns

Translated and Edited by

Adil Salahi

THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION

AND

ISLAMONLINE.NET

Published by

THE ISLAMIC FOUNDATION,

Markfield Conference Centre,

Ratby Lane, Markfield, Leicestershire LE67 9SY, United Kingdom

Tel: (01530) 244944, Fax: (01530) 244946

E-mail:

Website: www.islamic-foundation.org.uk

Quran House, PO Box 30611, Nairobi, Kenya

PMB 3193, Kano, Nigeria

ISLAMONLINE.NET,

PO Box 22212, Doha, Qatar

E-mail:

Website: www.islamonline.net

Copyright The Islamic Foundation 2004/1425 AH

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Qutb, Sayyid, 19031966

In the shade of the Quran: Fi zilal al-Quran,

Vol. 18: Surahs 78114: Al-Naba Al-Nas

1. Koran Commentaries

I. Title II. Salahi, M.A. III. Islamic Foundation

IV. Fi zilal al-Quran

297.1227

eISBN 9780860377009

Typeset by: N.A.Qaddoura

Cover design by: Imtiaze A. Manjra

Contents

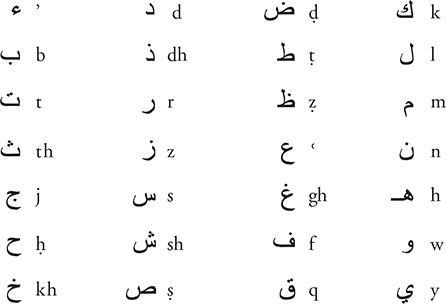

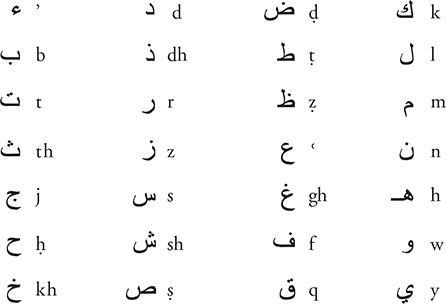

Consonants. Arabic

initial: unexpressed medial and final:

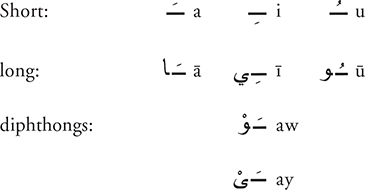

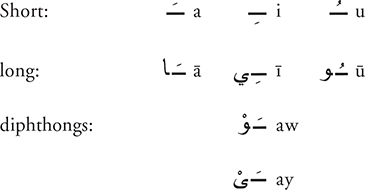

Vowels, diphthongs, etc.

Introduction by Adil Salahi

This volume represents the final part of the work undertaken by Sayyid Qub during the 1950s and 60s to explain the meaning of the Qurn. It was the first to be published in English and that by the Muslim Welfare House, London, 1979. Since then that edition has been reproduced many times, including several pirate editions. In its original form, this volume was assigned number 30, as it appears in the Arabic edition. This is in line with the original Arabic edition which conformed to the division of the Qurn into 30 equal parts, with little consideration given as to where the dividing lines occur. The idea being to enable the reader to recite the Qurn once a month, without much difficulty.

When the Islamic Foundation undertook the task of publishing the complete work in English, the decision was taken to dispense with the Arabic arrangement, and instead make the units of the Qurnic text, i.e. its srahs, the basis for arrangement. The Qurn contains 114 srahs, some of which are very short, with no more than one or two lines, while others are very long. Each one though is a complete unit, focusing on a central idea. The first eight volumes of this series contain one srah each, with the exception of Vol. I, which included the first srah, which is very short, together with the second, which is the longest in the Qurn. Thereafter, we incorporated a number of srahs into each volume, trying to make them all of similar length. Hence, the change in the number that appears on this volume, making it number XVIII.

But this is not the only change the present volume makes. A thorough revision has been undertaken, with numerous modifications introduced into the English version, including the rendering of Qurnic textual meanings. We trust that this has improved the quality of the work presented.

Translating such a work is not an easy task. Most people might appreciate such difficulty if they realized that it also involves rendering the meaning of the Qurn into English. The Qurn has been translated into English no less than 20 times. George Sales translation, the first in English, appeared in 1734, followed by J.M. Rodwells in 1861, then Palmers in 1880. The twentieth century saw a rapid rise in Qurnic translations, with a large number of new versions, many of which were put together by Muslim translators.

It is not our aim to discuss the merits and faults of these translations, nor to make any judgement in favour of any particular one. We only want to say that while most of these translations have considerable merit, an Arabic reader familiar with the language of the Qurn finds them inadequate, unable to convey the full meaning of the original text. Indeed, many of the translators have expressed the feeling that their rendering remains short of expressing the full sense of the text. Many resort to adding in parenthesis words and phrases that are not in the original text. They feel that only in this way can they make the English version closer to the Arabic original.

Perhaps this gives us a glimpse of the difficulty of the task of translating the Qurn into a European language. It also tells us something about the reasons that have motivated this long line of translators to attempt the same. There is no doubt that each one of them felt that he would be adding something that earlier translations had missed. Otherwise, he would consider himself to be undertaking a needless task. Nonetheless, the process continues, and today and in the future there will be no shortage of Qurnic translators who want to bring the art of Qurnic translation to a higher level of excellence.

Had the Qurn been an ordinary book, written by a human being, and had it been the subject of the efforts of such a long line of translators, we would have had a perfect translation a long time ago. But the fact that both its translators and discerning readers remain unsatisfied with the outcome of these efforts, individually and collectively, poses some questions that are very difficult to answer. Before publishing the first part of his translation, entitled The Message of the Qurn, the late Muhammad Asad published a pamphlet under the title Can the Qurn Be Translated? This has now been incorporated as the Foreword to his full translation which he describes as an attempt perhaps the first attempt at a really idiomatic, explanatory rendition of the Qurnic message into a European language.

Asad dwells at length on the Qurnic characteristic of jz, or brevity and word economy in Qurnic expression. It is this particular characteristic which presents the translator with the greatest difficulty. It is this that compels Asad to add numerous words and phrases in parenthesis in order to make the meaning clear. But word economy in the original text accounts for only one aspect of the difficulties encountered in translating the Qurn. If we were to compare the task to that of translating poetry, we can imagine the numerous difficulties the translator has to overcome in rendering the images and associations a poet deliberately brings together when selecting his words. While translating poetry into prose has to deal with this difficulty, the translator may overcome some of his problems by making his rendering somewhat explanatory, occasionally using a phrase in place of a word, or borrowing the occasional image in order to make the product closer to the meanings intended by the poet. But if poetry is to be translated into poetry, the difficulties are multiplied. The translator feels that he has no option but to depart from the form used in the original and focus on the ideas conveyed so as to express them in a different form, tapping the images and associations of the target language.

Next page