First published in 1930 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1930 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

ISBN 13:978-1-138-55385-9 (hbk)

ISBN 13:978-0-203-70485-1 (ebk)

THE NEW GENERATION

THE NEW GENERATION

THE INTIMATE PROBLEMS OF MODERN PARENTS AND CHILDREN

Edited by

V. F. CALVERTON AND

SAMUEL D. SCHMALHAUSEN

Co-Editors of

SEX IN CIVILIZATION

With An Introduction by

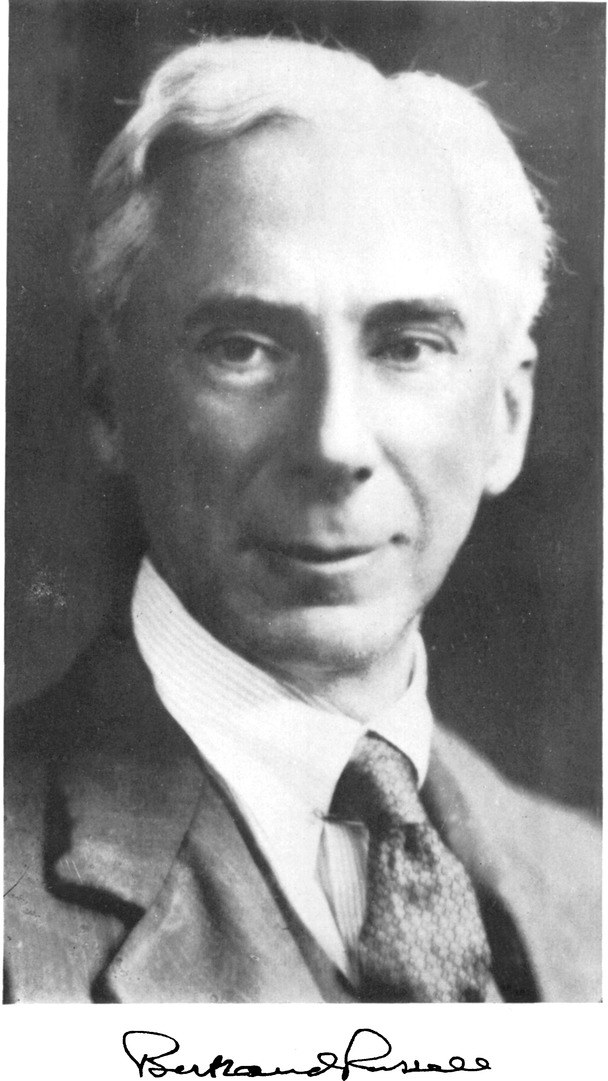

BERTRAND RUSSELL

LONDON

GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD.

MUSEUM STREET

F IRST P UBLISHED IN G REAT B RITAIN IN 1930

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO

THE PARENTS

AND CHILDREN

OF THE

NEWER GENERATION

PREFACE

T HE conflict between parents and children is older than civilization. Its heritage is primeval. While in earliest times parents and children were undoubtedly part of an integral collective unit, and in that sense linked together in a closer way than they ever have been in later periods, we find even then evidences of this conflict. Even when the group was a social whole in every respect, the tendency of mothers to usurp too much of the affection of their children was not absent as a cause of this conflict. Where over-fondness of mothers for their children or children for their mothers occurred, the spirit of social solidarity was impaired. In order to prevent young men from becoming weak and sentimental as a result of such affection, certain customs and practices have grown up among primitive peoples. Violence toward the mother was often encouraged as one method of defeating that evil. Among the Fijians and the Hottentots of Namaland boys are taught to strike their mothers, and, as Briffault points out, among the Iroquois and Apaches boys are required to wound their mothers with arrowsa neglect of which would beget a fear lest the child should grow up a coward. When the mothers submit to this treatment without protest, which is the general custom, it is because they have been taught to respect this gesture as necessary to the development of their children. Nevertheless, the essence of the struggle is there, however subtly it is rationalized.

The war of the generations, to be sure, has always been closely connected with the war of the sexes. In matriarchal days when women were dominantor even in such societies to-day where feminine rulership is still activethe sons were not taught to attack their mothers in order to develop the characteristic of manliness. In fact there the sons were less important than the daughters. It was only in patriarchal times that such customs arose. Before the beginning of agriculture, and the decline of the matriarchate, the history of the human race was the history of womankind. Since that time the history of the human race has been the history of mankind. Under each form, one sex was subordinated by the other. There have been revolts of the sexes in the past, the revolt of the Sabine women, the revolt of European women in the twelfth century, and the revolt of women to-day. While the status of children changed vastly between matriarchal and patriarchal timesamong many matriarchal peoples, for instance, it was the men and not the women who cooked the food and took care of the childrenit changed but little in comparison during the entire history of patriarchal civilization. Mothers have been the protectors of children and their first educators. Although men have continued to rule society, and have used every law and custom to enforce the subjection of woman, women by a kind of curious irony have managed to root themselves in a most subtle and pervasive way into the lives of their children. Men who denied them the right to vote, the right to property, the right to work, and even the right to think, nevertheless gave over to them their children to rear and instruct. By an inevitable cunning of instinct and impulse, mothers, through the advantage of physiological and psychological proximity, have wrapped themselves around the lives of children in a sense that has never been possible for fathers. While adopting the fathers name as their surname, in necessary respect of masculine dominancy, children have adopted their mothers psychology. If the father has represented rigid authority in the life of the modern family, the mother has represented persuasive power. The great compensation for women lay in that fact. Denied almost every right as human beings, they nevertheless found a consolation in the power, disguised to be sure as affection, which they could exercise over their children. Children were a necessity then for a happy life. Those women who did not have children had no form of consolation for their lives. And those women who had children not in accordance with the dominant masculine mores, that is, whose children were illegitimate, were attacked by women as well as men.

To-day this whole struggle has taken on a new form. Not only are women in revolt against men but children in turn are in revolt against their parentsin particular against their mothers. The most striking indication of this latter revolt is to be found in the vivid destruction of the power of mothers over their children. The beginning of this change is to be found in the Industrial Revolution which marked the beginning of the downfall of the family as a stable institution. Not only were proletarian mothers and proletarian children thrust into industry by the hundreds of thousands, but a whole set of new historical factors were set in motion that led more and more to the steady separation of mother and child. The most important of these factors was the institution of the public school. Prior to the inauguration of the public school as an institution in social life education was confined largely to the home. The public school marked the first definite break with that tradition. Much of the opposition that the public school idea met with in the early days of its organization was based on the consequences which were feared would result from this break. The public school took the child away from the mother at an early age, and by providing the type of instruction that went beyond the power of the home it slowly began the process of weaning the mind of the child away from its mother. To-day, with all the growth in education that has occurred, the mother plays an increasingly smaller part in the training of her children. And what with the development of nursery schools and kindergartens, the age at which the child is practically removed from the mothers influence has been reduced even more decisively still. The school in one form or another has taken the place of the home as the educational center, and the mother has been replaced by the teacher as educator.