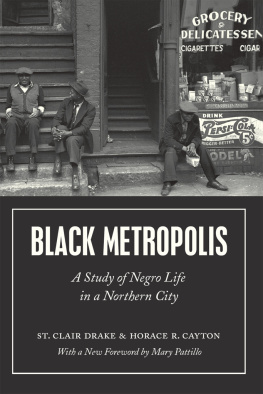

Originally Published 1944 by the University of Pennsylvania Press

Reprinted with a new Foreword 2001

Copyright 1944, 1971, 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fauset, Arthur Huff, 1899

Black gods of the metropolis : Negro cults of the urban North / by Arthur Huff Fauset

p. cm

ISBN 0-8122-1001-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Afro-AmericansReligion. 2. Afro-AmericansPennsylvaniaPhiladelphia. 3. CultsUnited States. I. Title. II. Szwed, John. III. Savage, Barbara Dianne

BR563.N4 F3

FOREWORD

WHEN the Philadelphia Anthropological Society sponsored the publication of Arthur Huff Fausets Black Gods of the Metropolis in 1944, his fellow members at the Society considered him uniquely qualified to conduct a study of black religious cults in Philadelphia. Himself partly of Negro origin, the Societys Publication Committee wrote in a foreword to the book, Fauset was endowed for this study with a background, a point of view, and an entre to the field which could never have been possessed by one of exclusively European tradition and descent.

By citing only his racial credentials without commenting on the study itself, the foreword vividly illustrated the paradoxical position of black social scientists as they alternately foiled and wielded the double-edged sword of racial essentialism. The Societys words also spoke to prevailing assumptions about the nature of the nexus between race, religion, and culture, ironically the central intellectual debate in the book.

Born in New Jersey in 1899, Fauset was the son of Redmon Fauset, a black African Methodist Episcopal minister, and of Bella White, a Jewish convert to Christianity. Fausets father died when his son was an infant. Fauset spent most of his youth in Philadelphia, where he graduated from Boys Central High School in 1916, the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy in 1918, and the University of Pennsylvania with an AB degree in 1921. He began a career as a teacher and was soon promoted to be a principal in the Philadelphia public school system, a position he held from the 1920s to the late 1940s.

During the 1920s, Fauset also pioneered the study of black folk culture and, like his much better-known older half-sister Jessie Redmon Fauset, engaged in literary pursuits as well. With encouragement from Alain Locke, Fauset turned to short story and essay writing; he won many awards, including an O. Henry Award for the best short story in 1926, and earned inclusion in several important anthologies. In addition to his love of writing, Fauset developed an interest in black folklore, which led him to the University of Pennsylvania to receive a masters degree in anthropology in 1924. Fauset published articles

Fauset had developed a commitment to political activism that came to full expression in the 1930s and 1940s. Frustrated by his own experience in the Philadelphia school system, he helped reorganize the local chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, later serving as one of its vice-presidents. Fauset founded a local political organization that worked with the NAACP to help end the Philadelphia Transit Companys refusal to hire black employees. He also wrote a weekly column of political commentary in Philadelphias black newspaper, the Philadelphia Tribune. Increasingly critical of national racial politics, he served for several years as the national vice-president of the National Negro Congress, working alongside labor leader A. Philip Randolph. His wife, Crystal Bird Fauset, also was politically active, becoming in 1938 the first black woman to be elected to a state legislature.

Fausets political views did not deter him from trying to become an officer in the armed forces during World War II, a step he took with the hope of helping black enlisted men. However, after successfully completing rigorous training and Officer Candidate School, he was denied a commission as an officer based on secret federal investigations into his political activities. Deeply disappointed, Fauset returned to Philadelphia and resumed work as a high school principal.

This is the life Arthur Huff Fauset had lived before he became the fourth black person to earn a PhD in anthropology, a degree he received from the University of Pennsylvania in 1942.

Half the text of Fausets book is devoted to case studies of five black religious sects in Philadelphia; the other half builds an interpretative framing for understanding the rise of cults, their appeal, and their implications for broader debates about African American religious practices. The case studies present us with a compelling example of urban ethnographic work. Based on two years of repeated visits to worship services and extended interviews with leaders and lay people, these case studies are presented in a dispassionate, respectful, and nonjudgmental tone. The fluidity and grace of the writing reflect Fausets broader abilities and experience in both narrative fiction and journalism, especially in its attention to telling descriptive detail.

Fauset profiled five different sects: Mt. Sinai Holy Church of America, Inc., a Christian holiness church founded by Bishop Ida Robinson; United House of Prayer for All People, a Bible-based sect led by Daddy Grace who emphasized a prosperity doctrine; Church of God, a group of so-called black Jews who taught that all white Jews were imposters and that Jesus was a black man; Moorish Science Temple of America, founded by Noble Drew Ali, who wrote his own Holy Koran and drew from the teachings of many prophets, including Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, and Confucius; and, perhaps the best known, the Father Divine Peace Mission Movement, an eclectic, racially egalitarian and communitarian group. By choosing to focus on these sects, Fauset did not follow the lead of other scholars at the time who designated as cults most Christian holiness, Pentecostal, and storefront churches. He distinguished the latter institutions by referring to them not as cults but as orthodox evangelical churches. He justified his inclusion of Mt. Sinai because of its charismatic founding bishop and its marriage restrictions which limited members to in-sect partners.

Whether intended or not, Fausets selections for study made it difficult for him and for his readers to easily draw comparisons or generalizations. His case studies point clearly toward the idiosyncratic nature of each of the groups. However, what his examples did offer then and now is a glimpse of the adventuresome range of religious ideas and practices that appealed to disparate groups of African Americans in the 1930s and 1940s. Because Fauset relied so heavily on oral interviews and personal testimony from the members of these groups, what is preserved in the book, to our great benefit, are the voices of ordinary black men and women explaining why they made the religious choices they did. So much of the scholarly attention given to African-American religion focuses on the leadership class, overlooking evidence of how lay people thought about and articulated their own spiritual needs and experiences.