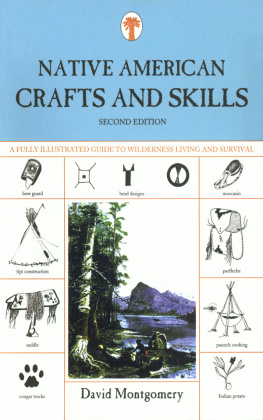

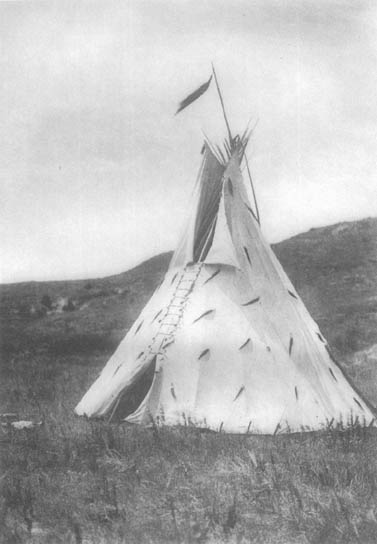

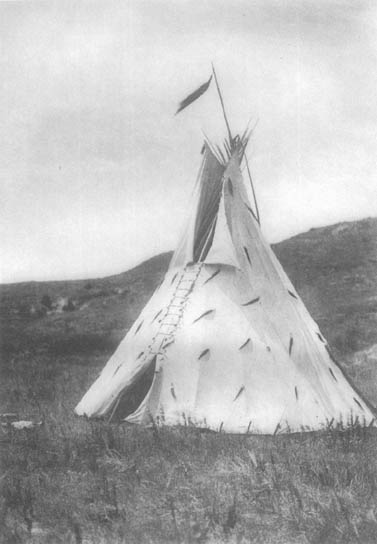

Tipi (Sioux: Plains)

SURVIVAL SKILLS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS

PETER GOODCHILD

SECOND EDITION

Goodchild, Peter.

Survival Skills of the North American Indians / Peter Goodchild.2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-55652-345-9

1. Indians of North AmericaIndustries. 2. Indians of North AmericaEconomic conditions. 3. HandicraftNorth America. 4. Survival skills. I. I. Title.

E98.I5G66 1999

The author and the publisher of this book disclaim all liability incurred in connection with the use of the information contained in this book.

1984, 1999 by Peter Goodchild

All rights reserved

Second edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 1-55652-345-9

Cover design by Barb Rohm

Photogravures reproduced from the Curtis Collection, 1907-1930, by Edward Sheriff Curtis, via Webmaster

Printed in the United States of America

C ONTENTS

Foreword

In college I had trouble believing that the hunters/gatherers I was studying could possibly have had warm lodges and full bellies. And the academic approach kept me from feeling that these people could actually be my forebears, or, for that matter, the forebears of any contemporary peoples. I needed to connect more by touch and taste and spirit. So I quit my job and moved to a small cabin deep in the northern forest.

In the first week I found sixteen kinds of edible berries within sight of my door; by years end I had built a snug bark lodge and was practicing many of the crafts and skills found in this book. I came to realize that native was not synonymous with cold and hungry; thatbarring special circumstancesthese native people likely led lives of relative comfort and ease.

One day in that first spring I was drawn to the lush, tender sprouts of a young basswood tree. Typically I would take the greens home and prepare a salad, but this time I bent the branches to my mouth and just munched. With the first nibble, dj vu overcame me: I was one of my distant kin feeding; I was a monkey gripping that branch; I was a buffalo grazing. Deep inside I then knew that my ancestors, and the ancestors of each and all of us, wore skins and danced to the drum and foraged and fashioned from Earths gifts.

Perhaps now, in these days, much of the difference between us as peoples lies in the varying number of generations we are removed from our forager ancestry. Perhaps we can find common ground by rekindling and renewing our link with that ancestry.

Tamarack Song,

Wilderness skills teacher and

author of Journey to the Ancestral Self

Preface

In order to be fully human, I occasionally need to put my hands on the green things that grow on the surface of this planet, because I and those leaves are one. My personal loss is proportional to my ability to destroy that unity. All flesh is grass. This is the essential fact of human life, physically speaking. The prophet Isaiah meant that human life is ephemeral, that it fades like the grass. Whenever those words have occurred to me, however, I have taken them out of context and had thoughts that are roughly the converse. If I walk across a vacant lot in the middle of the city, I see great squares of concrete, symmetric ledges with wormlike rods of rusted iron, and among all of it the grass is growing. A thousand years from now, the iron will have rusted away, the concrete will have dissolved, and the grass that grows there today will have seeded and reseeded itself. As a cool north wind blows soft clouds across the sky, countless blades of grass will be bending and rising in that breeze, beaten and brushed, rotting in winter, sparkling yellow-green in spring. Grass was growing on the earth long before human beings evolved, and I suspect that it will be growing there long after we are gone.

Grasses are the least of things to look at. Even among the few urbanites who are still nature lovers, although birds and fish and roses and maple trees may be regarded as beautiful to behold, I have never met anyone who has deliberately sat in bed late at night reading the first volume of Britton and Browns Illustrated Flora, a volume largely devoted to the Gramineae, the grasses. Perhaps it took fifty years of living for me to reach that stage, or perhaps the poet in me is giving way to the scientist, as happened to Thoreau in his later years. Grasses, like olives, are something for which we may have to acquire a fondness only slowly. They seem to lack beauty: their flowers are so small and undistinguished in color that for most people they do not exist. In fact, for a large part of a grasss life the plant is quite brown, so that it seems to be either dead or at least unhealthy; yet that brown dormancy is part of the seasonal cycle.

I have friends for whom anything green is an impediment. Naturally occurring vegetation is a sign of property in need of cement, and trees are Gods way of telling us to buy chain saws. As much as I love my friends, I do not always share their sentiments. Sometimes I feel that it is my duty to explain to them that there are nearly half a million species of plants on earth, and each one contains a universe of its own. No matter how narrowly we focus our attention, the stars and galaxies expand in our gaze. And so it happened that after fifty years of looking at grasses I realized that they are not all alike. Even here in Ontario, a northern land where the fauna and flora are therefore less numerous than elsewhere, I cannot walk in my own sub-urban backyard without encountering a dozen species of grass. I am quite aware of the diversity: my wife and I bought this hundred-year-old house only a year ago, and the first summer was spent disturbing this populous tenth of an acre, day after day, until the neighbors said, Oh, what a nice garden you have. Nice, yes, perhaps, but in the long struggle I gained an admiration for my competitors, the vegetation that was here before us.

The more I look, the more I see entrancing variety in the dull grasses that grow at my feet. Witch grass, if allowed to grow to its full size, has a flowering head as rich and full as the tail of an ostrich. The common bluegrass that grows in the lawn has blades that are shaped, at the tip, like the bows of tiny boats. Foxtail has compact heads with grains that make the plant look like a kind of miniature wheat. Barnyard grass, one of my favorite weeds (although my neighbors may not share my enthusiasm), has flowering heads with grains large enough that the plant was cultivated, thousands of years ago, by the native people of what is now the southwestern United States. Squirreltail grass, with its long fine fur, belongs to the same genus as cultivated barley.

Next page