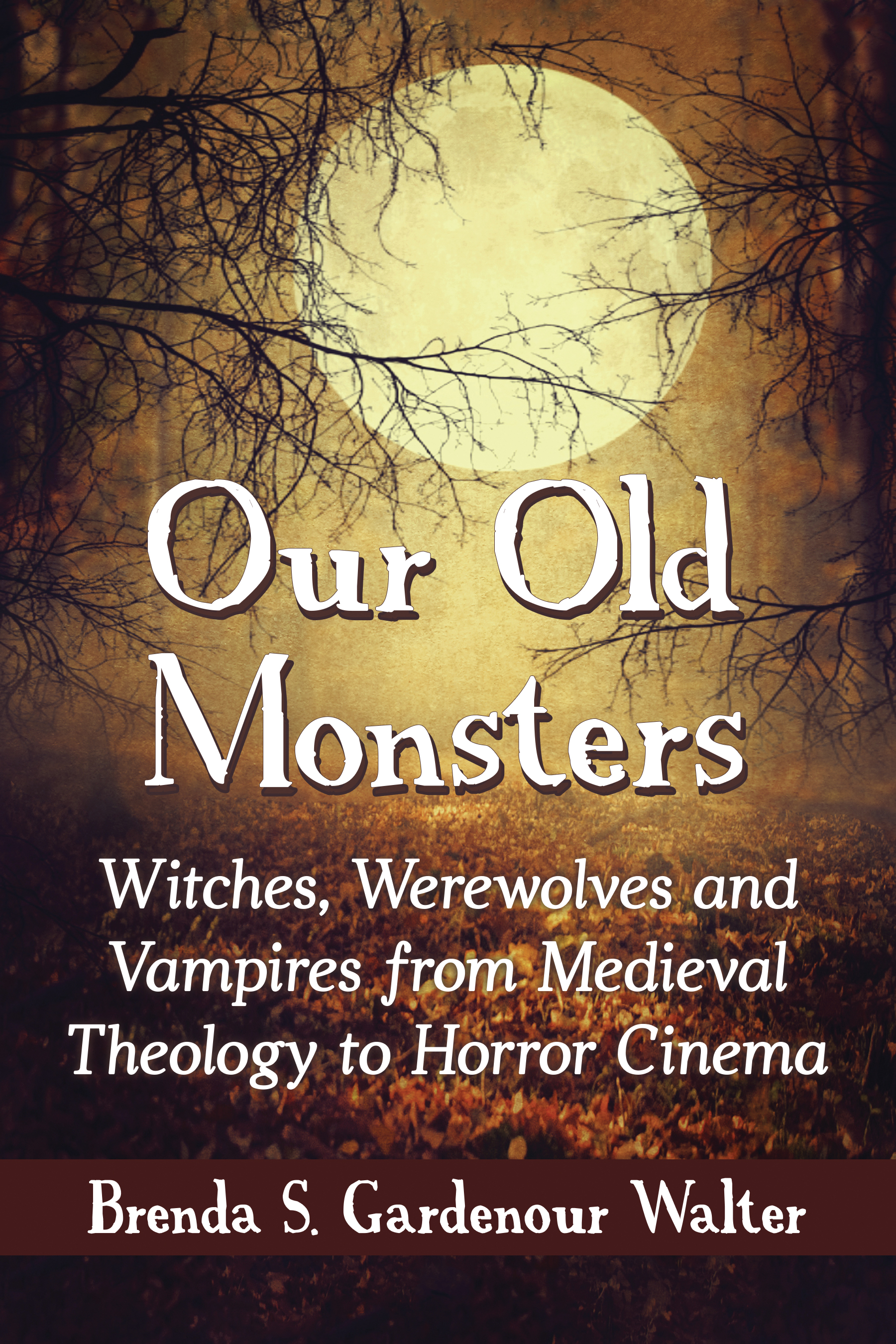

Our Old Monsters

Witches, Werewolves and Vampires from Medieval Theology to Horror Cinema

Brenda S. Gardenour Walter

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1942-2

2015 Brenda S. Gardenour Walter. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: moon in a forest 2015 iStock/Thinkstock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For the Munkey, the Man, and

all of the Melancholic Monsters

Preface

The modern horror genre is replete with perennially popular monstrous beings coded as evil, including the vampire, the witch, and the werewolf. Blood-hungry and melancholic, each of these old monsters share an inverted anatomy and physiology first codified in late-medieval universities. It was there that scholastic theologians such as Thomas Aquinas, William of Auvergne, and Pseudo-Albertus Magnus used Aristotelian cosmology and natural philosophy in conjunction with the authoritative language of medicine to construct the perfect Christian bodyrational, ethereal and fundamentally male.

Following the rules of Aristotelian contrariety, scholars likewise constructed the inverted, evil body, which was cold, irrational, earthbound and essentially female. Rapacious with bloodlust, its bowels infested with demons and rife with toxic pneuma, the melancholic monstrous body would inform the construction of the wicked witch, the hermeneutic vampireJew, and the mournful werewolf.

These old monsters remain popular in horror not only because of their alterity in myriad postmodern contexts, but also because of their essential humanity. Fully human and fully ensouled, they are creatures of the earth who, through their own self-willed weaknesses, have been tempted into damnation and fallen away from the love and acceptance they truly desire. In the postCartesian West where soulless zombies and disembodied ghosts haunt popular culture, these old monsters serve as mirrors in which we might observe with jouissance our own abjected selves, while suggesting the terrifying notion that our bodies are not merely haunted houses, but inhabited creations of flesh and blood searching for the light.

Introduction

What is the flaw of human rationality? It pretends not to see the horror and death at the end of the schemes it builds.Chief of Theory, Cosmopolis (2012)

Over the past twenty years, Western popular culture has witnessed a paranormal renaissance. Ghosts and demons haunt not only movie theaters but also our homes through myriad digital devices. Docudramas such as A Haunting (20052014) and Scariest Places on Earth (20002006), as well as paranormal investigation programs such as Ghost Hunters (2004-present), Ghost Adventures (2008-present), and Paranormal State (20072011), use POV (point of view) filming techniques, state of the art technology, and the testimony of both eyewitnesses and paranormal experts in their attempts to prove the veracity of the unseen world.

In conjunction with the paranormal renaissance, there has been a resurgence of the preternatural and the monstrous. Alongside postCartesian ghosts and zombies, the old monstersthe witch, the vampire, and the werewolfhave revived once again. Once relegated to the dustbins of Creature Double Features and midnight schlock, the old monsters are no longer marginalized but at the center of serial programming such as American Horror Story (2011present) and True Blood (2008present), as well as the books and films of the Twilight franchise. Some of this is generational; the old monsters are friends from childhood that we pass on to our own children in predictable cycles. Although their evil embodiment might give them the appearance of supernatural monstrosity, these creatures are nevertheless fully human, fully ensouled, and well within the bounds of medieval natural law. They are, in fact, usa sort of funhouse mirror reflecting back to our eye a warped, corrupted, and inverted image of our own potential human goodness.

Entangled with the resurgence of monsters in popular culture, monstrosity has become a topic of inquiry in recent scholarship. Discussions of the monstrous are by their very nature multivalent and often interdisciplinary. Scholars such as Timothy K. Beal have sought the sources of monstrosity in the Bible, while Jerome Jeffrey Cohen, Sarah Alison Miller, and Bettina Bildhauer have written about monstrous bodies, births, and blood in medieval contexts.

This book takes a novel approach, finding the sources for melancholic monstrosity in medieval scholasticism and examining the continued power of medieval structures to signify evil alterity in modern horror films. The first part, Medieval Foundations, begins in the learned milieu of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It was then that scholastic theologians reconciled the works of Aristotle and the precepts of learned medicine with the authority of received theology in order to create a single system meant to reflect a consistent divine truth. Chapter 1 traces the construction of divine goodness and Satanic evil found in sources such as the Summa Theologica and De Sententiis of Thomas Aquinas and the De Universo of William of Auvergne. Using Aristotelian cosmology and natural philosophy in the service of theology, scholars argued that the superlunary realm was one of divine perfection dominated by the Christian God who sat upon His throne in the Empyrean beyond the sidereal sphere.

Farthest from the Empyrean, the melancholic earth was the abode of Satan and his demonic minions who, having been cast down from heaven for their willful disobedience, might fly through the air but never again ascend into the ethereal realms beyond the moon. Weak and disobedient humans often fell prey to the demonic entities who tormented them, possessed them, and seduced them into the service of their dark lord. All those who did not conform to the authority of the Church, including heretics, witches, and nonChristians such as Jews and Muslims, were cast into the category of melancholic evil and imagined to be in league with the Devil. By the fifteenth century, famine, plague, schism, and heretical movements came to signify the strengthening power of Satanic entities, both human and demonic, who appeared to be mounting an organized and successful attack on the Church. It was in this context that Heinrich Kramer wrote the Malleus Maleficarum (1486), an inquisition manual that marked the beginning of a textual tradition in which the inverted category of Satanic evil, carrying the weight of theological authority, would be fully conflated with popular ideas about witchcraft. The upside-down world of subversion, inverted rituals, and Satanic worship that was increasingly circumscribed in early modern witchcraft treatises would become a universal signifier for evil alterity in Western culture, and one day serve as the substrate for supernatural horror.

Next page