THE ETERNAL WISDOM OF

Dr. Vassant V. Shirvaikar

The Eternal Wisdom of Dnyaneshwari

V. V. Shirvaikar

Copyright V. V. Shirvaikar 2013

Published By ZEN PUBLICATIONS at Smashwords

C O N T E N T S

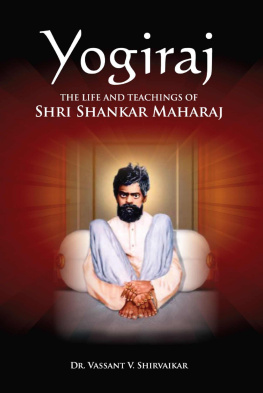

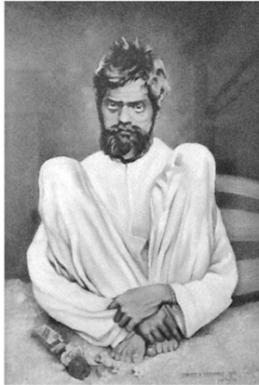

Sadguru Shri Shankar Maharaj

AUM

Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah

Sarve Santu Niramayah

Sarve Bhadrani Pashyantu

Ma Kashchit Dukha bhagbhaveta Om Shantih!

Om Shantih! Om Shantih!

AUM

Oh Lord! May all be happy.

May all be free from misery.

May all realise goodness and

may no one suffer pain.

Peace ! Peace ! Peace !

P R E F A C E

I t is more than seven centuries ago that Dnyaneshwar Maharaj wrote Bhavarthadeepika the commentary on Bhagvad-Gita on the instructions of his Guru and elder brother Nivruttinath (older only by two years) at the age of nineteen (though some say fifteen) years of age, but it is now better known as Dnyaneshwari after the author. It is written in ovi style verse traditional for Marathi religious literature.

Nivruttinath wanted this commentary to bring the philosophy of Bhagvad-Gita to common man, even a rustic. In those times, not only Vedic literature but most of the religious philosophical literature was in Sanskrit which only learned Brahmins knew and therefore outside the reach of common man. Most of such literature even otherwise was inaccessible to non-Brahmins leave alone a rustic farmer as the following lines from the eighteenth Chapter of Dnyaneshwari show:

The Vedas are full of Knowledge but there is none more miserly because they speak only with the first three castes. Others like women, shudras etc., who suffer tortures from this world, are not allowed under their shelter. I feel that in order to remove these earlier mentioned faults and with the intention of giving benefit to all, the Vedas have reappeared in the form of the Gita. Not only that, the Vedas are available to anybody through the Gita when its meaning enters in the mind, by listening to it or by reciting it. (18:1456-1460).

Greatness of Dnyaneshwari lies in the fact that it brought the philosophy of Gita and by that the philosophy of the Upanishads to common man. It became very popular; the ovis from it were and are even today melodiously sung in many households. Dnyaneshwari is regularly read in many households as part of their religious routine in spite of the fact that hardly anybody completely understands the seven centuries old Marathi language which is very much different from that spoken today. Fortunately, many prose translations are available and that satisfies the need of the curious who wish to understand the philosophy of Gita which by itself is also difficult to understand.

Dnyaneshwari became so popular that many people made copies (in pre-printing days it had to be by hand) for their use. But during this process many copies were produced with corrupted text. It was Saint Eknath who three centuries later collected many copies and prepared a corrected text which is what is available today. Fortunately unlike Ramayana and Mahabharata there is no indication that anybody has added his own text to the original.

In Dnyaneshwari Dnyaneshwar Maharaj explains each of the seven hundred shlokas of Bhagvad-Gita in detail through a number of ovis making skilful use of examples, similes and metaphors pertaining to natural phenomena and life situations familiar to the rural folk in Maharashtra. The 700 shlokas of Gita are explained in 9032 ovis. One wonders how an orphaned boy in his teens could know so much about lifen human traits and nature.

My real contact with Dnyaneshwari came quite late in life when I was about 58 years old and retired from service. I had purchased a copy of Dnyaneshwari (with a prose translation in Marathi by B. A. Bhide, published by Dhavale publications) as far back as in 1953 when I was twenty years old studying for the M. Sc. (Physics) course and later was engrossed in my job as a research scientist. This did not permit a mood conducive for reading spiritual literature of serious type. I did try once or twice to read it but could not go beyond the first few verses because it did not grip the interest. But that changed 37 years later when sometime in 1990 I received instructions to read and summarise the teachings of Dnyaneshwari in an easy language. That was how my closer acquaintance with the great work started.

It was difficult at first to understand Dnyaneshwari. The language of Dnyaneshwari is the eighth century old Marathi which most people do not understand well today. Also verse cannot express ideas as clearly and categorically as prose does. Fortunately, the Bhide book is quite comprehensive in that, it also gives ovi-by- ovi a prose translation as well as the corresponding original Gita Shloka (verse) and its Marathi translations by various saint poets in verse style viz., Samashloki of Vamanpandit, Arya of Moropant and ovi of Mukteshwar. This facilitated the understanding of the meaning not only of each Gita Shloka but also subject matter of the Dnyaneshwari verses. This was a great advantage to me because I have never learnt Sanskrit. The language of the Bhide book prose is somewhat archaic so I also consulted other Marathi prose translations, typically by Shri Keshavraomaharaj Deshmukh, a great spiritual person which is also in slightly archaic language and another by the scholar Mr. M. R. Yardi which is in a modern Marathi style. Later, I also consulted the English translation by another spiritual person, the Late Swami Umanand, the well- known yogini and disciple of Swami Muktanand of Ganeshpuri Siddhashram.

My assigned task was to make a composition to explain Dnyaneshwari that could be easily understood but I had to understand it first. I found myself confused while I read the text. Then I realized that this was mainly because Dnyaneshwar Maharaj had written this commentary with an objective that a common man, even a rustic farmer of his times, should understand it. Towards this end, he has used numerous similes and illustrative examples from common life and nature. For a modern reader one or two such similes and examples would have sufficed, but Dnyaneshwar Maharaj had chosen to use multiple similes and examples. It was those that were distracting the thread of logical philosophical thought. But for a modern educated and far better reader these extra similes etc., are not only superfluous but distracting. The first task therefore was to filter out the text to exclude them.