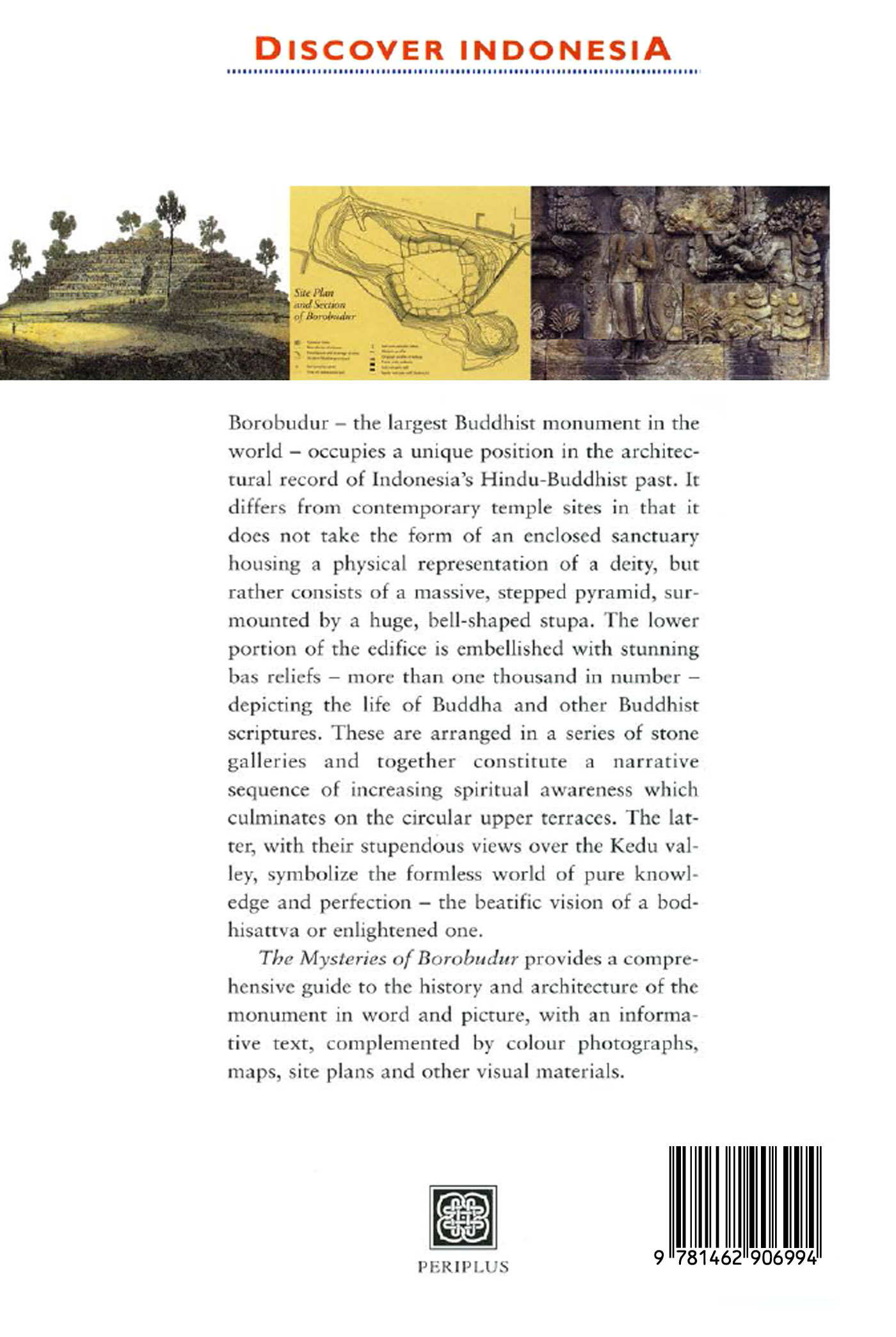

Buddhism In Java

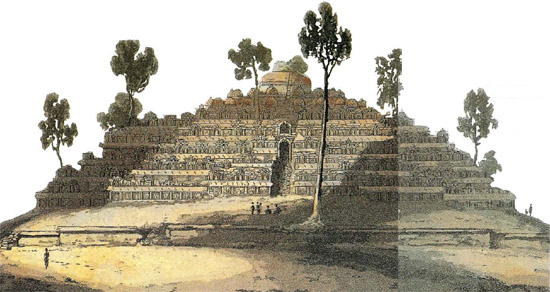

Buddhism enjoyed a short but intense period of popularity in central Java. All known Buddhist temples there, including Borobudur, were built within a century of one another, between AD 750 and 850.

Buddhism was not in a calm, stable state during the 8th and 9th centuries when Borobudur was built. On the contrary, this was a period of intense intellectual activity. Each teacher and each country where new forms of Buddhism were developed evolved special interpretations of the religion. Indonesians must have contributed their own concepts in addition to helping spread those from India.

Buddhism was less popular than Hinduism in ancient Java. It did, however, have powerful royal patrons and both Hinduism and Buddhism were linked to two families who formed the ruling elite of Javanese society during the Borobudur period: the Sanjaya and the Sailendra.

The meaning of the word "family" in ancient Java must be explained. The Javanese have never used family names, and Javanese trace their family relationships through both males and females. Groups of kinsmen coalesce around distinguished forebears while less important ancestors are forgotten.

Buddhism in Indonesia was closely linked to an influential family known as the Sailendra or "Lords of the Mountain." This title clearly indicates that the family claimed an intimate relationship with the supernatural power which the Javanese believed hovered around mountain peaks.

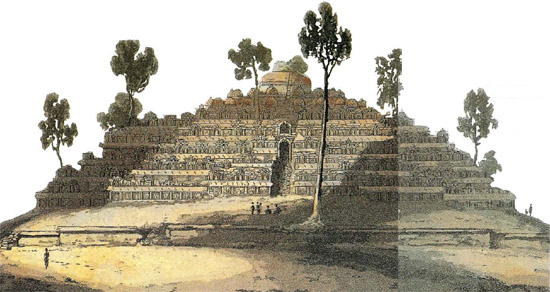

The very first published view of Borobudur, which appeared in the second edition of the monumental work, The History of Java, written by Java's Lieutenant-Governor, Thomas Stamford Raffles. This view was based on a sketch by H.C. Cornelius (see page ), it depicts large trees growing upon the monument which do not, however, obscure the main outline of the structure.

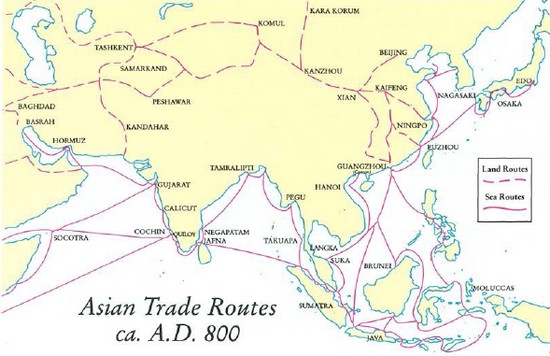

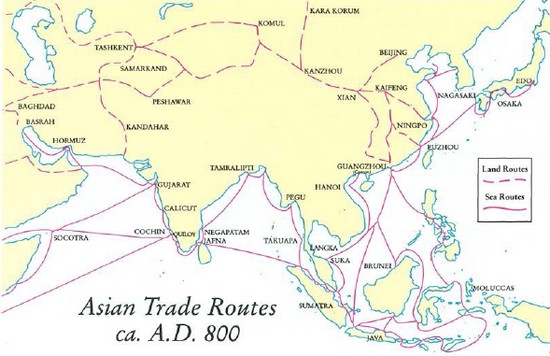

As early as 2,000 years ago, many parts of the vast Asian continent were already linked by well-established trade routes. Buddhism spread from India to mainland and insular Southeast Asia along these land and sea routes during the first millennium AD.

Asian Trade Routes ca. A.D. 800

The Sailendra became the dominant political family in Java around AD 780, when they displaced the Sanjaya, an older elite who were devotees of Hinduism and had been important since at least AD 732 the date of the earliest known inscription to mention a kingdom in central Java.

Tension between members of the Sailendra and Sanjaya families must have stemmed from competition for political status, but probably had no effect on religious practices. Religion has never been a source of contention or conflict among the Javanese. The two families inter-married with the result that the children could give their loyalty to either the Sailendra or the Sanjaya.

In AD 832 the Sailendra queen, Sri Kahulunan, married a Sanjaya known as Rakai Pikatan. Pikatan gave donations to various Buddhist sanctuaries, but devoted his greatest resources and energy to the construction of the stunning Hindu complex at Prambanan.

Pikatan's reign was not entirely peaceful. Inscriptions and legends allude to war with a Sailendran prince, Balaputra, who aspired to become paramount ruler. The prince was defeated and fled to Sumatra. After about AD 850, the Sanjaya held supreme power in Java, and without the support of the Sailendra, no more great Buddhist monuments were built on the island.

Traders along the Silk Route introduced Buddhism to China during the first centuries AD, and the new religion soon acquired a firm foothold beside the indigenous Chinese beliefs of Taoism and Confucianism.

A sea link between India and China was forged around AD 400. This new route was opened by Indonesian sailors who had several centuries of experience in maritime trade with other parts of Southeast Asia and India. Buddhist pilgrims voyaged with increasing frequency through the archipelago during the 7th and 8th centuries. The records they have left tell us that Java and Sumatra were major centers of international Buddhist scholarship during this period.

Jatakas and Avadanas

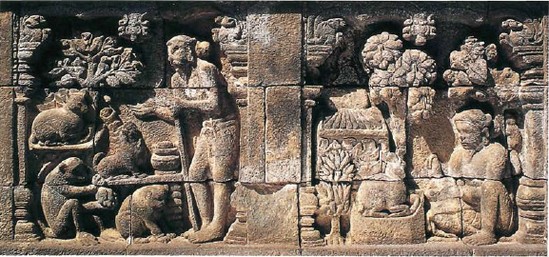

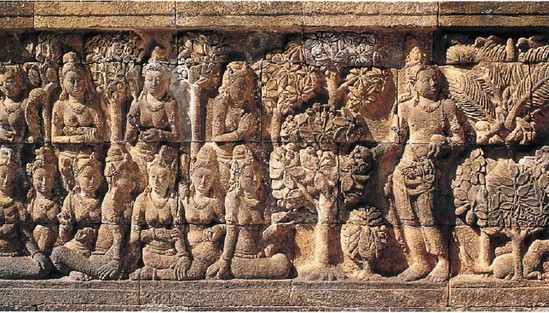

Borobudur illustrates quite a number of jataka and avadana stories in just a few panels. The stories can be compared to animal fables, fairy tales, romances, and adventure stories. Some avadanas have very little religious significance.

A scene from Story 8 in the Jatakamala series: the future Buddha, on horseback, is attacked by a band of ogres, but is unharmed.

Jataka, or "Birth Story," narratives depicting acts of self-sacrifice performed by Buddha in his earlier incarnations, and avadanas, or "Heroic Deeds"similar stories which differ from jatakas only in that the main character is not Buddha in an earlier incarnationfill 500 panels on the balustrade of the first gallery and 120 panels on the main wall (beneath the Lalitavistara, see following pages), and another 100 panels on the balustrade of the second gallery, a total of 720 panels.

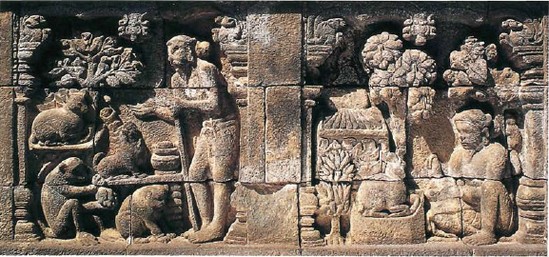

A scene from Story 6: the future Buddha as a rabbit. When Indra (left) arrives disguised as a Brahman, the rabbit's three friends-a jackal, an otter and an ape-all bring food. He is unable to do so, and instead jumps into the fire himself.

The Jatakamala Birth Stories

The stories essentially promote the notion of self-sacrifice. Numbers in parentheses refer to the lower series of relief panels on the first balustrade (IB.b), numbered consecutively from the east stairway and proceeding clockwise. The first eight stories are:

Story 1 (panels 1-4): The future Buddha becomes a hermit in the mountains and meets a starving tigress, to whom he gives his body as food.

Story 2 (5-9): The future Buddha is a king. The god Indra comes in disguise as a blind man and Buddha gives him his eyes.

Story 3 (10-14): A man and woman who give food to monks are reborn as a king and queen.

Story 4 (15-18): The future Buddha as head of a merchant guild. He and his wife take food to a monk although to do so they have to pass over hell.

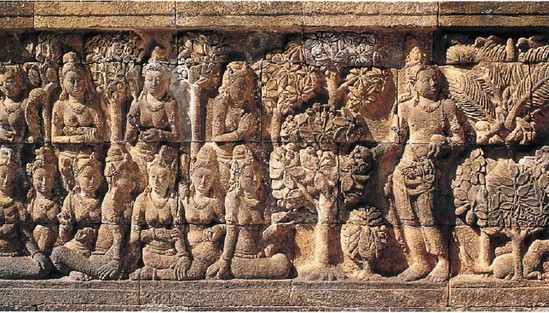

The merchant Maitrakanyaka greeted by 16 nymphs (here represented by 11). Each time he moves to a new city, more apsaras (supernatural female beings) come out to greet him.

Story 5 (19-22): Reborn as a rich and highly charitable man, the future Buddha is tested by Indra, who steals his possessions. The future Buddha becomes a humble grasscutter, but retains his generous nature and is rewarded.

Story 6 (23-25): The future Buddha is a rabbit who teaches his friendsa jackal, an otter and an apethe importance of generosity. When Indra appears disguised as a Brahman, his friends all bring food, but the rabbit is unable to do so and jumps into the cooking fire himself.

Story 7 (26-28): The future Buddha is a rich man, but becomes a hermit. As a reward for his charity to a BrahmanIndra in disguisehe is granted his wish: food of the gods in order to feed the poor.