A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

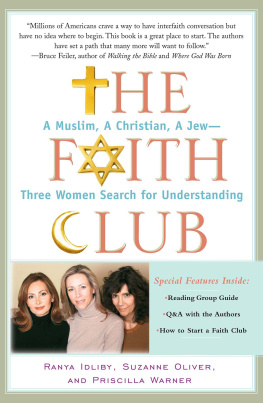

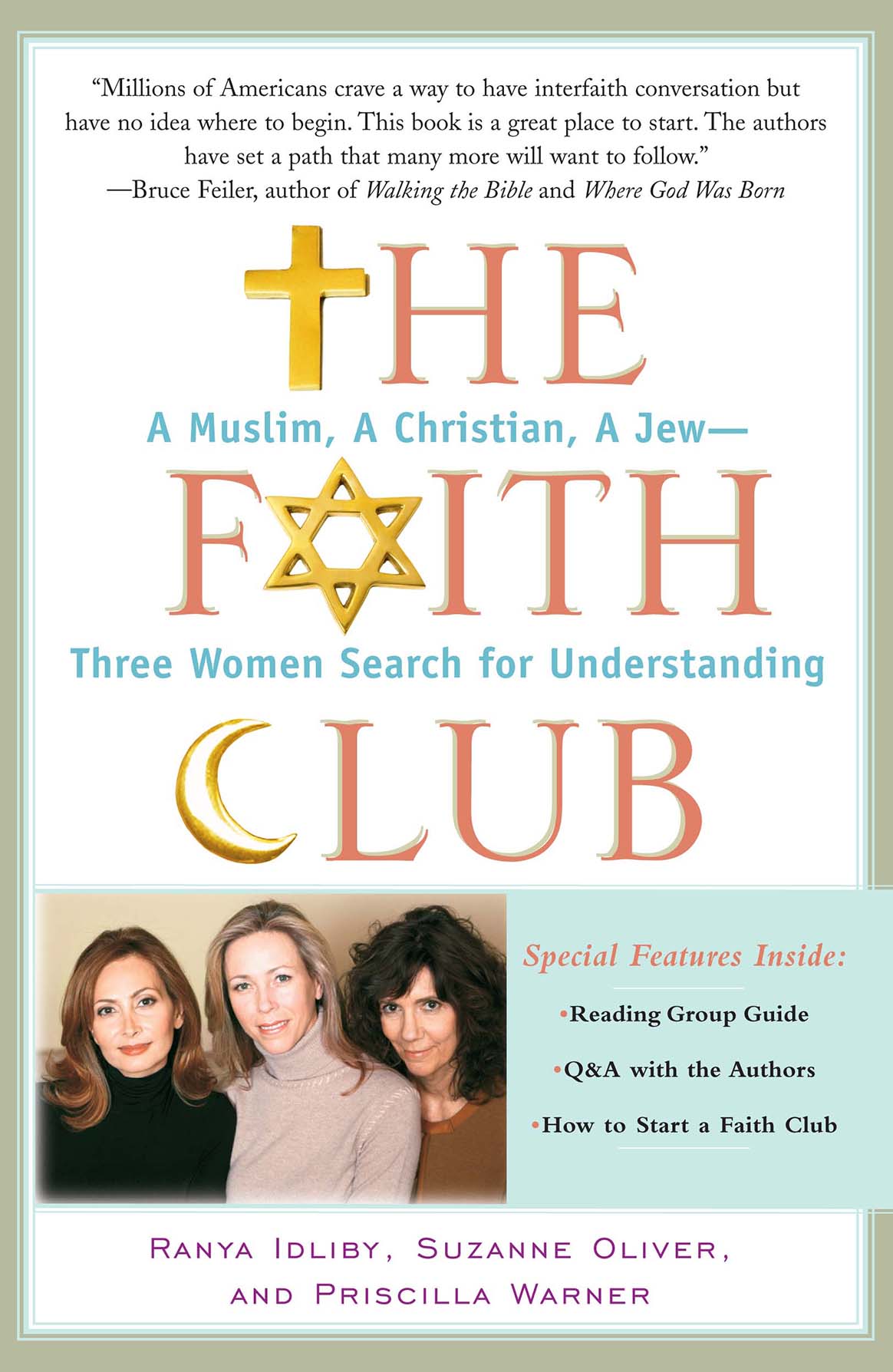

Copyright 2006 by Ranya Idliby, Suzanne Oliver, and Priscilla Warner

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

ATRIA PAPERBACK and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Davina Mock

Text of the song Cor Meum Est Templum Sacrum by Patricia Van Ness, copyright 1993 PatriciaVanNess.com. Epitaph by Merritt Malloy used by permission of Merritt Malloy. Excerpts from Gates of Repentance, The New Union Prayer Book for the Days of Awe are copyright 1979 by Central Conference of American Rabbis and used by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Idliby, Ranya. The faith club: a Muslim, Christian, Jewthree women search for understanding / Ranya Idliby, Suzanne Oliver, Priscilla Warner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references. 1. Idliby, Ranya. 2. Oliver, Suzanne. 3. Warner, Priscilla. 4. ReligionsRelations. 5. JudaismRelationsChristianity. 6. Christianity and other religionsJudaism. 7. JudaismRelationsIslam. 8. IslamRelationsJudaism. 9. IslamRelationsChristianity. 10. Christianity and other religionsIslam. I. Oliver, Suzanne. II. Warner, Priscilla. III. Title.

BL410 .I35 2006

201.5dc22 2006045408

ISBN: 978-0-7432-9047-0

ISBN: 978-0-7432-9048-7 (Pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-7432-9862-9 (ebook)

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonandSchuster.com

For Leia and Taymor

and all Abrahams children

Burdens are the foundations of ease

and bitter things the forerunners of pleasure.

JELALLUDDIN RUMI

For Anne, Thomas, and Theodore,

with gratitude for my sister Kristin

Judge not, and you will not be judged;

condemn not, and you will not be condemned;

forgive, and you will be forgiven;

give, and it will be given to you;

good measure, pressed down, shaken together,

running over, will be put into your lap.

For the measure you give will be the measure you get back.

LUKE 6:37

For Jimmy, Max, and Jack

When two people relate to each other

authentically and humanly,

God is the electricity that surges between them.

MARTIN BUBER

Preface

Meet the Faith Club. Were three mothers from three faithsIslam, Christianity, and Judaismwho got together to write a picture book for our children that would highlight the connections between our religions. But no sooner had we started talking about our beliefs and how to explain them to our children than our differences led to misunderstandings. Our project nearly fell apart.

We realized that before we could talk about what united us we had to confront what divided us in matters of faith, God, and religion. We had to reveal our own worst fears, prejudices, and stereotypes.

So we made a commitment to meet regularly. We talked in our living rooms over cups of jasmine tea and bars of dark chocolate. No question was deemed inappropriate, no matter how rude or politically incorrect. We taped our conversations and kept journals as we discussed everything from jihad to Jesus, heaven to holy texts. Somewhere along the way, our moments of conflict, frustration, and anger gave way to new understanding and great respect.

Now we invite you into our Faith Club to eavesdrop on our conversations. Come into our living rooms and share our life-altering experience. Perhaps when youre finished, you will want to have a faith club of your own.

Chapter One

In the Beginning

Ranya:

The phone rang on the morning of September 11th. It was my husband, screaming for me to turn on the TV. With sheer horror, I watched as the second plane hit the World Trade Center.

Please dont let this be connected to Islam, I thought desperately.

As the city began to mourn, churches and temples opened their doors for worship and emotional support. I longed for a mosque, or a Muslim religious leader, an imam, who could help support my family during this horrific time. I needed a spiritual community, a safe haven where we could seek comfort.

Back then, I knew of no alternative Muslim voice that could represent the silent majority of Muslims, no nearby place where we could congregate. I did not feel comfortable at the mosque in our neighborhood, where women prayed separately from men. I wanted to feel respected. I longed to enter a mosque on an equal footing with Muslim men, to be treated as an equal, as I know I am in the eyes of God.

Tensions rose, and as some Muslims, or those mistaken for Muslims, were attacked or rounded up for questioning, I began to feel self-conscious about our Muslim identity. I was concerned and fearful for the security of my children as American Muslims. I avoided calling my son by his Muslim name, addressing him in public only by his nicknames, Ty and Timmy. When my grandmother came to visit, I asked her not to speak Arabic in public. And when my parents were in New York, they were approached by a stranger who advised them not to speak Arabic on the street. A well-meaning friend, trying to make me feel better (and warning me not to take it the wrong way), told me that my family and I dont look Muslim. This, she thought, might protect us from discrimination. What were Muslims supposed to look like, I wondered?

My husband and I were challenged on both fronts, by Muslims abroad who questioned the very possibility of a future for our children as American Muslims of Arab descent, and on the home front, by the stereotypes and prejudices that were heightened by the attacks of 9/11. On street corners, people joked about Muslim martyrs racing to heaven to meet their brown-eyed virgins, a supposed reference to the Quran, but something I had never heard before. While we took heart from our presidents visit to the mosque in Washington, D.C., we were also aware of the voices within his own administration who felt he had gone too far and who maintained that, at its core, Islam was a militant and dangerous religion. I wondered who was representing my faith.

Although my husband and I had at first chosen to spare our children the details of the attacks, we soon found out that our kindergarten-age daughter, who was the only Muslim in her class, was learning a great deal from friends at school. We explained to her that evil men who were Arab and called themselves Muslim had performed an evil deed. Since her only experience of the Arab world overseas had involved her grandparents, she anxiously asked if her grandmother knew these men or was involved in any way.

Soon thereafter, my daughter came home from school and asked me a simple question: Do we celebrate Hanukah or Christmas? Her friends at school wanted to know. I wasnt sure how to respond. I worried that the reality of 9/11 had made it unworkable for my children to be both Muslim and American. Would their sense of belonging be compromised? Would they as Americans feel burdened by their religion and heritage? So far Id tried to raise my children with moral character and pride in their Muslim heritage despite the fact that we did not practice many specific religious rituals or worship at a mosque. We do celebrate a commercial kind of Christmas. But were Muslims. We believe Jesus was a prophet, not the son of God. How could I give my daughter an intelligent, clear answer that she could confidently deliver to other kindergarteners? Was there such an answer? As a concerned parent I created a challenge for myself: If I was unable to give my children good reasons why they should remain Muslims, other than out of pure ancestral loyalty, I would not ask them to remain true to Islam, a religion that had come to seem to me to be more of a burden than a privilege in America.