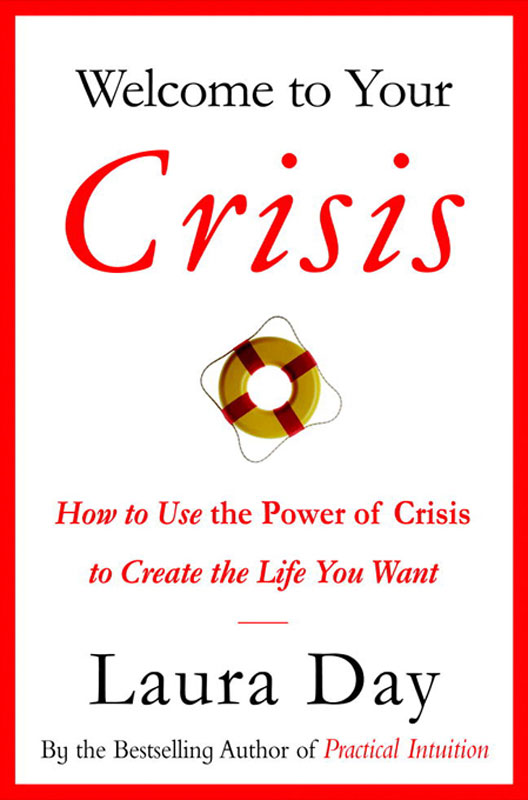

Copyright 2006 by Laura Day

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

Little, Brown and Company name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: May 2006

ISBN: 978-0-7595-1583-3

Also by Laura Day

THE CIRCLE

PRACTICAL INTUITION IN LOVE

PRACTICAL INTUITION FOR SUCCESS

PRACTICAL INTUITION

I dedicate this book to my dear friend and the godfather of my son Samson, Kevin Huvane. Thank you for your vision. Thank you for your faith. And thank you for always having a solution at three oclock in the morning (Pacific Standard Time). Ralph Waldo Emerson said that every wall is a door. Thank you for proving him right!

W elcome to your crisis?

The idea that a crisis might have some positive aspects probably sounds unfeeling. Crises are painful, difficult, and threatening situations, to be sure. I wouldnt wish a crisis on anyone.

Unfortunately, crises are inevitable features of our lives. Learning how to navigate crises well, then, is a crucial life skill. And since not all crises can be avoided, why not meet them head on and embrace them? As youll discover shortly, crises force us to make long-overdue changes in our lives and can serve as catalysts for remarkable positive transformations.

If we allow them to.

The insights and recommendations in this book are based on my own observations and experiences in helping people and organizations handle crises. Some key elements in my methodology are corroborated by the work of others, such as Hans Selye in the field of stress (Selye observed that positive events can induce just as much stress as do many negative ones), Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in the field of optimal human functioning (who observed that we feel most alive when our abilities are fully engaged by challenges), and sociologist Charles Fritz in the field of human behavior during disasters.

Fritzs seminal observations about disasters offer compelling insights into how you and I should handle our personal crises. If a crisis is bad, a disaster must be that much worse. Yet as Fritz pointed out, disasters reveal positive truths about human behavior. As in crises, disasters elicit many of our best qualities as human and social beings. So can our crises.

Disasters have been in the news this past year, most poignantly in the instance of the devastation wreaked on New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina. Closer to my home, I have witnessed other disasters in my own neighborhood. I live in New York City, mere blocks from the site of the former World Trade Center.

So I speak from firsthand experience when I point outas Im sure you have experienced in any disasters youve witnessed up closethat far from leading to chaos or worse, disasters often bring out the best in people. Weve all seen news coverage of looting and other acts of predatory opportunism that occur during disasters. While such acts may make for riveting journalism, they are by far the exception rather than the norm. In disasters most people act with compassion, selflessly and tirelessly working together to help others afflicted by the disaster.

The key aspect of a disaster that minimizes its harm, as it inspires and ennobles everyday people, is that the experience is shared. The impact of Hurricane Katrina was so horrific precisely because the flood itself prevented people from acting as a community and from sharing the disasters emotional, psychological, physical, and other burdens.

Crises and disasters sound awful, and indeed they are. Our daily lives, by contrast, seem prosaic if not idyllic. If we are honest with ourselves, however, a closer look at our lives reveals a different reality. Our routine, everyday lives are filled with conflicts, stresses, and frustrations. Even when we are not beset by petty concerns and obligations, our lives rarely demand our full engagement; much of the time we are simply going through the motions. And apart from our families and close friends, and to a lesser degree our neighbors, we live in an atomized, fragmented society, having little interaction with those around us. The key point here is we keep our everyday crises, in sharp distinction with the shared experience of public disasters, well hidden from others, sometimes even from our closest friends and loved ones.

What lessons can we learn from the inspiring heroism and effectiveness of individuals during disasters that we can apply to our handling of the crises in our personal lives? Lets examine the characteristics of disasters to see how they overlap with or differ from the characteristics of our personal crises.

A disaster dwarfs everything else in the lives of those affected. A disaster simplifies and streamlines our lives. In a disaster, the most pressing needs are concrete and relegate all other needs to the background as minor distractions to the real work that must get done. Notice that in a disaster, few people are as bad off as are the worst affected. Everyone focuses on the plight of those worse off, and the entire community is galvanized to participate in relief efforts.

A were-all-in-this-together attitude prevails, and a new communitythose affected by the disasterarises to address the most urgent needs. Everyone pitches in to help and is given a sense of mission, a larger purpose outside themselves, and the resulting tight-knit social solidarity of the disaster community is astonishing.

Because the disaster was caused by something external, individuals do not blame themselves or others for their misfortune, nor does anyone feel guilt or shame. Everyone feels free to open up and communicate with others in the disaster community, providing mutual physical and emotional support. Mourning and grieving for the disasters losses, suffering, and privations are intense, but shared by many.

Two of the key features of disaster relief, then, are the importance of sharing as much as possible, and of taking care of business. Contrast this effective functioning in the face of public disaster with the ineffective handling with which most of us grapple with our private crises. Most of us tend to keep our crises to ourselves, often out of shame. We allow the crisis to overwhelm our ability to get on with our mundane, day-to-day obligations.

I come from a family of doctors and have been an intuitive healer for my entire adult life. In the field of medicine, the word crisis has a specific meaning: that sudden point in the course of a disease when the disease either gets dramatically worse or turns around and gets dramatically better. Our everyday crises present us with similar junctions, at which our lives can turn dramatically worse or dramatically better depending on the actions we take. I wrote this book to help you make sure your path out of crisis is both positive and enriching.

M any people who pick up this book sense that they need a big changeeither in themselves or in their lives. Even readers who feel that everything is going great in their lives still feel that something is not working, that something is missing.

Who in normal circumstances consults an intuitive healer? Consulting an intuitive is not like going to a physician for a physical checkup.