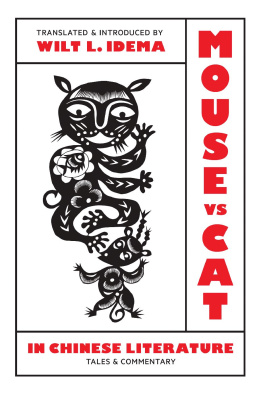

MOUSE VS. CAT

IN CHINESE LITERATURE

Mouse vs. Cat in Chinese Literature was published with the support of the Robert B. Heilman Endowment for Books in the Humanities, established through a generous bequest from the distinguished scholar who served as chair of the University of Washington English Department from 1948 to 1971 .

This publication was also supported by grants from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and the Harvard-Yenching Institute.

Copyright 2019 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Arno Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

Cover illustration: Paper-cut illustration by Yu Ping and Ren Ping , from the The Marriage of Miss Mouse (Beijing: Sinolingua, 1993 )

232221201954321

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

university of washington press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Idema, W. L. (Wilt L.), author. | Lee, Haiyan, writer of foreword.

Title: Mouse vs. cat in Chinese literature / Wilt L. Idema; foreword by Haiyan Lee.

Other titles: Mouse versus cat in Chinese literature

Description: First edition. | Seattle : University of Washington Press, [ 2019 ] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: lccn 2018023657 (print) | lccn 2018032514 (ebook) | isbn 9780295744841 (ebook) | isbn 9780295744858 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780295744834 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: lcsh : Chinese literatureHistory and criticism. | Cats in literature. | Mice in literature. | Rats in literature. | TalesChina. | Fables, Chinese.

Classification: LCC PL 2265 (ebook) | lcc PL 2265 .I 2019 (print) | ddc ./dc

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2018023657

The paper used in this publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ansi z 39.48 1984 .

Contents

by Haiyan Lee

.Thieving Rats and Pampered Cats

Rapacious Rats

Deserving Mice

Performing Mice

Revered Rats

Wildcats and Pussycats

Buddhist Cats

Good Mousers and Lazy Pets

Demonic Cats

Cat Lovers and Cat Lore

.The White Mouse and the Five Rats

The White Mouse

The Five Rats

The Execution of the Five Rats

.A Wedding and a Court Case

The Marriage of the Mouse

The Court Case

Other Genres

The Mutual Accusations of the Cat and the Mouse

The Scroll of the Accusation of the Mouse against the Cat

.A Tale without Shape or Shadow

Expanding the Court Case

Prequels: Creation and Pride

Prequels: The Crashed Wedding

Prequels: The War of the Mice against the Cat

A Tale without Shape or Shadow

.Peace Negotiations and Dystopias

Actualized Versions of the Court Case

Modern and Contemporary Authors on Cats and Rats

:Cats and Mice in Love and War from East to West

Foreword

The Lives and Troubles of Others

Haiyan Lee

in a meandering, occasionally snarky essay titled Dogs, Cats, and Mice, written in 1926, the great Chinese writer Lu Xun reminisces about a thumb-size mouse he once rescued from a snake and kept as a pet when he was a young boy. The cute little rodent, known as a yinshu (literally shadow mouse, or mole rat), enjoyed his tender affection because he was able to fasten onto it his enduring fascination with a New Year print near his bed called The Wedding of the Mouse. He describes the picture this way: From the groom and the bride to the best man, bridesmaid, guests, and attendants, each sported a pointy chin and slender legs, looking rather refined like scholars; nonetheless, all were decked out in garish clothes. I thought, who can mount such a pageant but my favorite shadow mice?

In many parts of China well into the twentieth century, a minor ritual observance during the monthlong New Year celebration consisted of retiring to bed early on a given evening (the date varies according to the locale) owing to the folk belief that on such a day mice conducted their matrimonial affairs and that it was prudent not to disturb them, or else there would be endless mice trouble in the year to come. An environmentally minded modern reader may well consider this custom indicative of a bygone way of life that embedded humans in a cosmological order that included the divine as well as the nonhuman and that fostered an attitude of proper respect, even deference, toward the teeming lifeworld beyond humanity. Although in some quarters there is a tendency to simplify this attitude as the Eastern way of living harmoniously with Nature, one cannot deny that a tradition that extended consideration to as lowly and universally detested creatures as mice and rats at least one day a year was animated by a cosmology radically different from the one that fueled the mass campaigns launched by Mao Zedong to exterminate the four pests in the 1950s. In the latter case, it was all about giving no quarter. Most notoriously, people turned out in great numbers in the open to bang loudly on pots and pans to prevent sparrows labeled as pests for stealing grainsfrom landing, until the hapless birds dropped from the sky from exhaustion and fright.

Surely, the status of mice and rats as vermin is less in doubt than that of sparrows, and since ancient times they have been the object of contempt, resentment, and disgust. Most memorably, they are invoked in The Book of Odes (Shijing) as an allegory of the rich and powerful who plunder the common folk to fatten themselves. Yet during the New Year festivities they are given a wide berth and their arguably parasitical way of life is granted a measure of legitimacy and even dignity. It certainly helps that they seem good at mimicking human sociability and organizing their society through the orderly exchange of females. Apparently, they, too, lead a civilized life, even if it cuts across that of humans in pesky ways. The ambivalence is unmistakable, enough to give wings to the fantasy life of a young boy growing up in the twilight years of imperial China.

For readers reared on a diet of Disney cartoons, there is perhaps nothing novel about anthropomorphizing mice into adorable icons of human desires and foibles. But there are interesting differences, and they become clear when we examine the rich repertoire of folk narratives revolving around the clash between the cat and the mouse showcased in this collection. Many of these tales tell of an elaborate sequence of events meant to explain why the mouse has a reasonable grievance against the cat, which usually has to do with the cats raid of the mouses wedding party. In doing so, the tales raise profound questions about the moral hazard of anthropomorphism: If animals serve so well to illustrate human morals, on what grounds do we justify excluding them from moral concern? Is there a bright line between animals as symbols and animals as creaturely beings?

Wilt L. Idema, the compiler and translator of these fantastic tales, points out that there is a relative dearth of talking animals in traditional Chinese literature, and that the present collection presents some of the most notable exceptions. Indeed, the archetypes of animal symbolism that populate our contemporary global popular culture are derived mostly from non-Chinese folklores and literary genres: the prideful hare, the cunning fox, the loyal dog, the conniving snake, and so on. As historians of science Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman maintain, this is the predominant way in which humans think with animalsby reducing animals to stick figures to stand for quintessential human attributes. Nonetheless, these furred, feathered, and finned characters hold our interest because they are more than animals; instead, they are almost always cast in moral molds, either having to partake of human moral conflicts or having to navigate their own moral dilemmas, or both. Not surprisingly, it is the dog and the horse that are the darlings of this genre, given the ease with which they are incorporated into morality tales about loyalty, betrayal, and sacrifice.

Next page